Spaceland (8 page)

Authors: Rudy Rucker

We raced across the Central Valley, Momo's little flying saucer buzzing steadily beneath us. The surfaces of things were lit by the moon, and their insides were lit by the higher light of the All. The beauty of it was soothing to me. We passed barns, farmhouses, rivers, freeways, and 7-Elevens. And then we were following Route 101 into the south side of San Jose, with a fair amount of traffic even at this ungodly hourâwhat was it now, three AM on Sunday morning? Pitiful early risers out to beat the morning rush, and there was a rush, even on Sundays.

I could see each and every passenger in each and every car, and

each person in every bed in every house of the suburban developments rushing by. All the little lives, as pointless as my own.

each person in every bed in every house of the suburban developments rushing by. All the little lives, as pointless as my own.

Finally, we were closing in on the friendly interior of my home, lit up by the heartbreaking kitchen light that Jena had left on. Momo plowed on in there and then shoved me over into regular space. I was home. Me and a metal case with a million dollars in it. I would have given every bit of that money to roll the clock back a few hours. I'd been a fool to yell at Jena. I started crying.

“You are weary,” said Momo, a crooked cross section of her head peering into my living-dining room.

“Just go away. Don't ask me for anything more.”

Momo left and I got in the shower and stayed there till the crying stopped. And then put the case with the million. next to the bed and lay down. I was feeling calmer. I'd say it was all my fault. That I'd driven Jena away. Tomorrow I could fix things. I'd get her back. And then I'd get even with Spazz. I fell asleep.

A Dream Of Flatland

In the

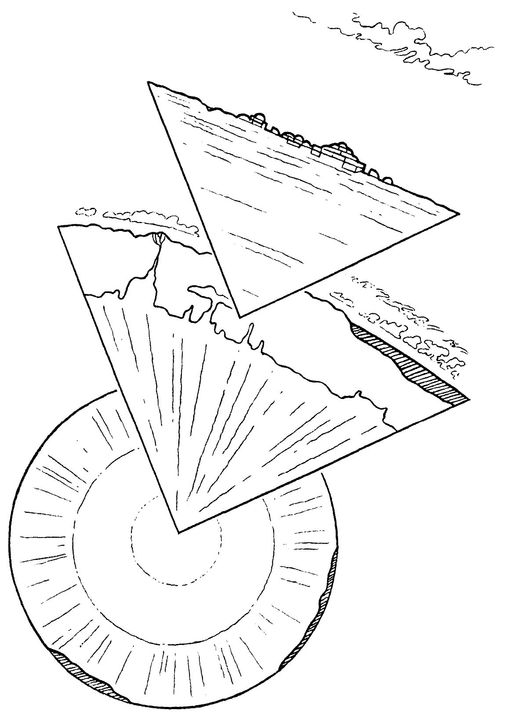

night I had a memorable dream. I was flying beside a huge vertical plane with something like a painting on it. The flat round image showed a full-size cross section of planetâglowing red in the center, and with mountains and shallow seas on its rind. I flew towards the disk's top border, driven by an urgent feeling that there was something I had to do.

night I had a memorable dream. I was flying beside a huge vertical plane with something like a painting on it. The flat round image showed a full-size cross section of planetâglowing red in the center, and with mountains and shallow seas on its rind. I flew towards the disk's top border, driven by an urgent feeling that there was something I had to do.

I stopped just short of the plane, which was more like a soap film than a canvas. Looking over at the rim of the disk, I saw movements. It wasn't a painting, it was a world of life. A Flatland. It had the East/West and up/down directions, but it was missing what we'd call North/South.

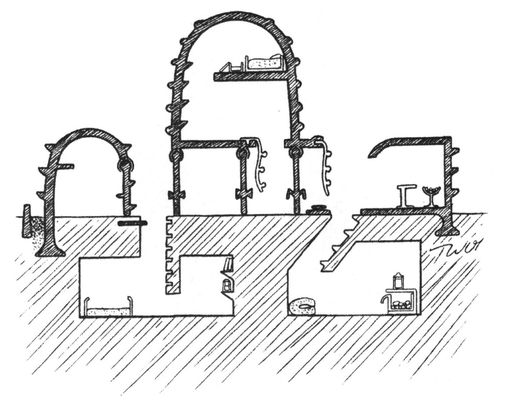

The top rim of the disk was a strip of land with two-dimensional building piled on it, making up a town Somehow thought of as my hometown of Matthewsboro, Colorado. It was like a cross section of Matthewsboro, a jumble of stuff set upon the line of a flat planet's gently curved rim. The town wasn't flat like an aerial view, it was flat like a vertical slice of a city. A cartoon skyline, with the insides of the buildings open to my views. It had dirt below, sky above, a row of buildings with little pieces of street between them and flat people everywhere.

The people of Flat Matthewsboro were nearly as tall as me. Each had two arms, two legs, and a head; they were like silhouettes, like animated Egyptian hieroglyphs. Their heads had an eye on either side and the slit of a mouth on top. The eyes were flat gleaming triangles, and the fronts of their eyes bulged. Their flat skins wrapped around their edges like rinds on slices of salami. Their clothes were stringy wrappers outside their skins, like threads of icing on the rims of gingerbread men and women.

Though these Flatlanders were as tall as me, they were no thicker than their film of space. Seeing a flat man on his own in an underground room, I flew down next to him. I said a few words to him, but he didn't seem to hear me. Would it hurt his space if I reached into it? I thought of an ocean's surface or a soap film. Maybe the surface would give way and stay tight around my fingers. I went ahead and stuck my two hands into the room with him. Just as I'd hoped, the space harmlessly gave way.

The flat man saw the cross sections of my fingers in his room; he darted around in terror. I cornered him against the eastern wall. From my viewpoint in the third dimension, I could see his insides: his muscles, his bones, his brain and his desperately pounding heart. Curious to get a really good look at how he was made, I grabbed hold of his skin on either side and lifted him up.

What a disaster. He fell apart like a hot slice of pizza with too many toppings. As his skin came up out of his plane, his innards spilled out and scattered. Some pieces drifted off into space, some fell back into the plane. I tried to put the man back together, but it was hopeless. There was nothing more to do for him. Sadly I stirred his remains with my hands, trying to get a feel for this flat world's matter. It was like the objects in this world were scraps of cellophane embedded in a soap film. They had a weak kind of solidity to them, but mostly they depended on the upper and lower sides of their space to keep them together. The flat man had been like a mosaic held together by the pressure of his space.

A Flatland woman appeared outside the room's door, which was hinged on the ceiling like a pet door. The door was like a line

instead of a rectangleâa fat line that bulged out to a ball at the top end, the ball held by a socket on the ceiling. The vibrations of the woman's knocking and of her voice traveled up my arms and into my ears. “Hey Custer, it's me, Mindy!” she cheerfully called.

instead of a rectangleâa fat line that bulged out to a ball at the top end, the ball held by a socket on the ceiling. The vibrations of the woman's knocking and of her voice traveled up my arms and into my ears. “Hey Custer, it's me, Mindy!” she cheerfully called.

The door swung open and her greetings changed to screams. I pulled my guilty hands up out of the room, but not before she glimpsed their pink cross sections. She ran up the carved-out stairs and onto the main street of Flat Matthewsboro, shrieking out the news.

I offered dead Custer a silent apology, and moved along next to the main street of Flat Matthewsboro myself, heading the opposite way from Mindy. Flat Matthewsboro's street ran East/West, punctuated by the town's buildings. It was more like a series of courtyards than a street. The buildings had staircase outlines, big on the bottom and small on top, with basements and sub-basements as well. I could see inside everything.

The citizens of Matthewsboro moved along the streets by walking upon their weirdly jointed legs and occasionally leaping into the air. They were nimble as fleas. The gravity of their world was so weak that they usually chose to clamber over a building rather than finding their way through its passages. And when two of them encountered each other going opposite ways, one would somersault over the other. It seemed customary for the westbound one to hop over the eastbound one.

The building's doors were sturdy affairs, with leaf springs to hold them closed. It occurred to me that if anyone ever left a one-room building's eastern and western doors open at the same time, the building could collapse. To make this less likely, the buildings with more than one door had more than one room as well, so that there were a series of doors. There even seemed to be some kind of signaling system to prevent the all-doors-open-at-once disaster, a system of strings rigged up along the ceilings between the pairs of doors.

The buildings had markings in the form of colored dashes and dots along their outer walls. Thanks to the magic of dreams, I could read the signs. I saw a hot dog stand that I remembered from my boyhood: Cowboy Zeke's Dawg 'N Suds. I watched a man eating a Wrangler Dog; he chewed it up and swallowed the pieces down into the sack of his stomach, washing down the food with a two-dimensional bottle of root beer. The woman behind the T-shaped counter had popped off the two-dimensional bottle-cap for him; the cap was a neat little thing shaped like a staple.

In my dream I knew that the flat man was my Dad. This hadn't mattered at first, but now it did matter. Dad reached up high to wipe off the mouth on the top of his head, then leaned on the counter of the hot dog stand, pointing his mouth towards the

shapely young counter woman, bulging out his eyes so that he could look at her. They got into a lively conversation. I reached out and gently touched the surface of the flat world so that the sounds of their voices could travel up my arm and into my inner ear. The Flatlanders sounded country, just like the folks back in the real Matthewsboro.

shapely young counter woman, bulging out his eyes so that he could look at her. They got into a lively conversation. I reached out and gently touched the surface of the flat world so that the sounds of their voices could travel up my arm and into my inner ear. The Flatlanders sounded country, just like the folks back in the real Matthewsboro.

The woman's name was Dawna. Dad wanted Dawna to come for a walk and let him “pitch some woo.” Dad often talked that way, using that forties kind of big-band slang. Some women liked it. Dawna sealed up the hot dog stand and they set off, scrambling over building after building until they'd found their way into the woods to the east of Matthewsboro.

The woods were like the cross section of a broccoli plant: green and filled with nooks and crannies. Beyond the woods lay the shallow bowl of a lakeâa water-filled dent in the planet's surface. People were swimming in the lake, diving to pass under each other when necessary. There was steady foot traffic back and forth over the woods between Matthewsboro and the lake, but the daytrippers stuck to the outmost edges of the vegetation rather than pushing down into its depths. Dad and Dawna were as private as a pair of aphids in a tea rose.

I watched them bend their heads to rub their mouths together, and then they peeled off their clothes, the thin strings they wrapped around themselves to hide their skin. How small their clothes were compared to their bodies.

Dad's penis stiffened between his legs. He and Dawna folded and bent their double-jointed legs so they could have sex. Dawna helped Dad insert tab A into slot B. It looked so strange from the third dimension.

A teenage girl was passing westward over the outer edges of the woods, on her way home from swimming in the lake. She looked familiar, but for the moment I couldn't place her. She wore her hair glued into two ponytails below her eyes, one ponytail on either side of her head. She had a little pet with her, a small darting animal like a dog. The pet unexpectedly burrowed down into a narrow inlet of the woods, and the girl followed after it. Perhaps the dog was drawn by Dad and Dawna's rustlings. The ponytailed girl saw the two lovers, but they didn't see her. Very agitated, the girl grabbed her dog and took off towards Matthewsboro.

Other books

Who's Afraid of Mr Wolfe? by Hazel Osmond

Shadow Zone by Iris Johansen, Roy Johansen

Dead Heading by Catherine Aird

Shallow Pond by Alissa Grosso

Kay Springsteen by Something Like a Lady

Burned by Natasha Deen

A Lady's Secret Weapon by Tracey Devlyn

The Dawn of a Dream by Ann Shorey

El psicoanálisis ¡vaya timo! by Ascensión Fumero Carlos Santamaría