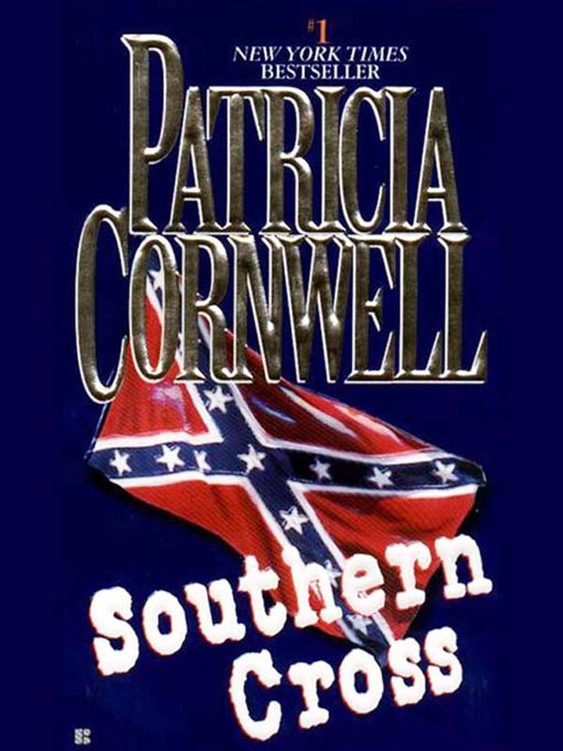

Southern Cross

Authors: Patricia Cornwell

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

SOUTHERN CROSS

A

Berkley

Book / published by arrangement with the author

All rights reserved.

Copyright ©

1998

by

Cornwell Enterprises, Inc.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

The Penguin Putnam Inc. World Wide Web site address is http://www.penguinputnam.com

ISBN: 978-1-1012-0372-9

A

Berkley

BOOK®

Berkley

Books first published by The Berkley Publishing Group, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

Berkley

and the “

B

” design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

First edition (electronic): July 2001

Also by Patricia Cornwell

P

OSTMORTEM

B

ODY OF

E

VIDENCE

A

LL

T

HAT

R

EMAINS

C

RUEL AND

U

NUSUAL

T

HE

B

ODY

F

ARM

F

ROM

P

OTTER

’

S

F

IELD

C

AUSE OF

D

EATH

H

ORNET

’

S

N

EST

U

NNATURAL

E

XPOSURE

P

OINT OF

O

RIGIN

S

CARPETTA

’

S

W

INTER

T

ABLE

L

IFE

’

S

L

ITTLE

F

ABLE

B

LACK

N

OTICE

R

UTH

, A P

ORTRAIT

: T

HE

S

TORY

OF

R

UTH

B

ELL

G

RAHAM

This is a work of fiction. The events

and characters portrayed are imaginary.

Their resemblance, if any, to real-life

counterparts is entirely coincidental.

T

O

M

ARCIA

H. M

OREY

World champion in juvenile justice

reform and all you’ve ever done

For what you’ve taught me

T

HE LAST

M

ONDAY

morning of March began with promise in the historic city of Richmond, Virginia, where prominent family names had not changed since the war that was not forgotten. Traffic was scant on downtown streets and the Internet. Drug dealers were asleep, prostitutes tired, drunk drivers sober, pedophiles returning to work, burglar alarms silent, domestic fights on hold. Not much was going on at the morgue.

Richmond, built on seven or eight hills, depending on who counts, is a metropolitan center of unflagging pride that traces its roots back to 1607, when a small band of fortune-hunting English explorers got lost and laid claim to the region by planting a cross in the name of King James. The inevitable settlement at the fall line of the James River, predictably called “The Falls,” suffered the expected tribulations of trading posts and forts, and anti-British sentiments, revolution, hardships, floggings, scalpings, treaties that didn’t work and people dying young.

Local Indians discovered firewater and hangovers, and traded herbs, minerals and furs for hatchets, ammunition, cloth, kettles and more firewater. Slaves were shipped in

from Africa. Thomas Jefferson designed Monticello, the Capitol and the state penitentiary. He founded the University of Virginia, drafted the Declaration of Independence and was accused of fathering mulatto children. Railroads were constructed. The tobacco industry flourished and nobody sued.

All in all, life in the genteel city ambled along reasonably well until 1861, when Virginia decided to secede from the Union and the Union wouldn’t go along with it. Richmond did not fare well in the Civil War. Afterward, the former capital of the Confederacy went on as best it could with no slaves and bad money. It remained fiercely loyal to its defeated cause, still flaunting its battle flag, the Southern Cross, as Richmonders marched into the next century and survived other terrible wars that were not their problem because they were fought elsewhere.

By the late twentieth century, things were going rather poorly in the capital city. Its homicide rate had climbed as high as second in the nation. Tourism was suffering. Children were carrying guns and knives to school and fighting on the bus. Residents and department stores had abandoned downtown and fled to nearby counties. The tax base was shrinking. City officials and city council members didn’t get along. The governor’s antebellum mansion needed new plumbing and wiring.

General Assembly delegates continued slamming desktops and insulting one another when they came to town, and the chairman of the House Transportation Committee carried a concealed handgun onto the floor. Dishonest gypsies began dropping by on their migrations north and south, and Richmond became a home away from home for drug dealers traveling along I-95.

The timing was right for a woman to come along and clean house. Or perhaps it was simply that nobody was looking when the city hired its first female police chief, who this moment was out walking her dog. Daffodils and crocuses were blooming, the morning’s first light spreading across the horizon, the temperature an unseasonable

seventy degrees. Birds were chatty from the branches of budding trees, and Chief Judy Hammer was feeling uplifted and momentarily soothed.

“Good girl, Popeye,” she encouraged her Boston terrier.

It wasn’t an especially kind name for a dog whose huge eyes bulged and pointed at the walls. But when the SPCA had shown the puppy on TV and Hammer had rushed to the phone to adopt her, Popeye was already Popeye and answered only to that name.

Hammer and Popeye kept a good pace through their restored neighborhood of Church Hill, the city’s original site, quite close to where the English planted their cross. Owner and dog moved briskly past antebellum homes with iron fences and porches, and slate and false mansard roofs, and turrets, stone lintels, chased wood, stained glass, scroll-sawn porches, gables, raised so-called English and picturesque basements, and thick chimneys.

They followed East Grace Street to where it ended at an overlook that was the most popular observation point in the city. On one side of the precipice was the radio station WRVA, and on the other was Hammer’s nineteenth-century Greek Revival house, built by a man in the tobacco business about the time the Civil War ended. Hammer loved the old brick, the bracketed cornices and flat roof, and the granite porch. She craved places with a past and always chose to live in the heart of the jurisdiction she served.

She unlocked the front door, turned off the alarm system, freed Popeye from the leash and put her through a quick circuit of sitting, sitting pretty and getting down, in exchange for treats. Hammer walked into the kitchen for coffee, her ritual every morning the same. After her walk and Popeye’s continuing behavioral modification, Hammer would sit in her living room, scan the paper and look out long windows at the vista of tall office buildings, the Capitol, the Medical College of Virginia and acres of Virginia Commonwealth University’s Biotechnology Research Park. It was said that Richmond was becoming

the “City of Science,” a place of enlightenment and thriving health.

But as its top law enforcer surveyed edifices and downtown streets, she was all too aware of crumbling brick smokestacks, rusting railroad tracks and viaducts, and abandoned factories and tobacco warehouses with windows painted over and boarded up. She knew that bordering downtown and not so far from where she lived were five federal housing projects, with two more on Southside. If one told the politically incorrect truth, all were breeding grounds for social chaos and violence and were clear evidence that the Civil War continued to be lost by the South.

Hammer gazed out at a city that had invited her to solve its seemingly hopeless problems. The morning was lighting up and she worried there would be one cruel cold snap left over from winter. Wouldn’t that be just like everything else these days, the final petty act, the eradication of what little beauty was left in her horrendously stressful life? Doubts crowded her thoughts.

When she had forged the destiny that had brought her to Richmond, she had refused to entertain the possibility that she had become a fugitive from her own life. Her two sons were grown and had distanced themselves from her long before their father, Seth, had gotten ill and died last spring. Judy Hammer had bravely gone on, gathering her life’s mission around her like a crusader’s cape.

She resigned from the Charlotte P.D., where she had been resisted and celebrated for the miracles she wrought as its chief. She decided it was her calling to move on to other southern cities and occupy and raze and reconstruct. She made a proposal to the National Institute of Justice that would allow her to pick beleaguered police departments across the South, spend a year in each, and bring all of them into a union of one-for-all and all-for-one.

Hammer’s philosophy was simple. She did not believe in cops’ rights. She knew for a fact that when officers, the brass, precincts and even chiefs seceded from the department to do their own thing, the result was catastrophic. Crime rates went up. Clearance rates went down. Nobody

got along. The citizens that law enforcement was there to protect and serve locked their doors, loaded their guns, cared not for their neighbors, gave cops the finger and blamed everything on them. Hammer’s blueprint for enlightenment and change was the New York Crime Control Model of policing known as COMSTAT, or computer-driven statistics.

The acronym was an easy way to define a concept far more complicated than the notion of using technology to map crime patterns and hot spots in the city. COMSTAT held every cop accountable for everything. No longer could the rank and file and their leaders pass the buck, look the other way, not care, not know the answer, say they couldn’t help it, were about to get around to it, hadn’t been told, forgot, meant to, didn’t feel well or were on the phone or off duty at the time, because on Mondays and Fridays Chief Hammer assembled representatives from all precincts and divisions and gave them hell.

Clearly, Hammer’s battle plan was a northern one, but as fate would have it, when she presented her proposal to Richmond’s city council, it was preoccupied with infighting, mutiny and usurpations. At the time, it didn’t seem like such a bad thing to let someone else solve the city’s problems. So it was that Hammer was hired as interim chief for a year and allowed to bring along two talents she had worked with in Charlotte.

Hammer began her occupation of Richmond. Soon enough stubbornness set in. Hatred followed. The city patriarchs wanted Hammer and her NIJ team to go home. There was not a thing the city needed to learn from New York, and Richmonders would be damned before they followed any example set by the turncoat, carpetbagging city of Charlotte, which had a habit of stealing Richmond’s banks and Fortune 500 companies.

Deputy Chief Virginia West complained bitterly through painful expressions and exasperated huffs as she jogged around the University of Richmond track. The slate roofs of handsome collegiate Gothic buildings were just

beginning to materialize as the sun thought about getting up, and students had yet to venture out except for two young women who were running sprints.

“I can’t go much farther,” West blurted out to Officer Andy Brazil.

Brazil glanced at his watch. “Seven more minutes,” he said. “Then you can walk.”

It was the only time she took orders from him. Virginia West had been a deputy chief in Charlotte when Brazil was still going through the police academy and writing articles for the

Charlotte Observer.

Then Hammer had brought them with her to Richmond so West could head investigations and Brazil could do research, handle public information and start a website.

Although one might argue that, in actuality, West and Brazil were peers on Hammer’s NIJ team, in West’s mind she outranked Brazil and always would. She was more powerful. He would never have her experience. She was better on the firing range and in fights. She had killed a suspect once, although she wasn’t proud of it. Her love affair with Brazil back in their Charlotte days had been due to the very normal intensity of mentoring. So he’d had a crush and she had gone along with it before he got over it. So what.

“You notice anybody else killing himself out here? Except those two girls, who are either on the track team or have an eating disorder,” West continued to complain in gasps. “No! And guess why! Because this is stupid as shit! I should be drinking coffee, reading the paper right now.”

“If you’d quit talking, you could get into a rhythm,” said Brazil, who ran without effort in navy Charlotte P.D. sweats and Saucony shoes that whispered when they touched the red rubberized track.

“You really ought to quit wearing Charlotte shit,” she went on talking anyway. “It’s bad enough as is. Why make the cops here hate us more?”

“I don’t think they hate us.” Brazil tried to be positive about how unfriendly and unappreciative Richmond cops had been.

“Yes they do.”

“Nobody likes change,” Brazil reminded her.

“You seem to,” she said.

It was a veiled reference to the rumor West had heard barely a week after they had moved here. Brazil had something going on with his landlady, a wealthy single woman who lived in Church Hill. West had asked for no further information. She had checked out nothing. She did not want to know. She had refused to drive past Brazil’s house, much less drop by for a visit.

“I guess I like change when it’s good,” Brazil was saying.

“Exactly.”

“Do you wish you’d stayed in Charlotte?”

“Absolutely.”

Brazil picked up his pace just enough to give her his back. She would never forgive him for saying how much he wanted her to come with him to Richmond, for talking her into something yet one more time because he could, because he used words with clarity and conviction. He had carried her away on the rhythm of feelings he clearly no longer had. He had crafted his love into poetry and then fucking read it to someone else.

“There’s nothing for me here,” said West, who put words together the way she hung doors and shutters and built fences. “I mean let’s be honest about it.” She wasn’t about to paint over anything without stripping it first. “It sucks.” She sawed away. “Thank God it’s only for a year.” She pounded her point.

He replied by picking up his pace.

“Like we’re some kind of MASH unit for police departments,” she added. “Who were we kidding? What a waste of time. I don’t remember when I’ve wasted so much time.”

Brazil glanced at his watch. He didn’t seem to be listening to her, and she wished she could get past his broad shoulders and handsome profile. The early sun rubbed gold into his hair. The two college women sprinted past, sweaty and fat-free, their muscular legs pumping as they showed

off to Brazil. West felt depressed. She felt old. She halted and bent over, hands on her knees.

“That’s it!” she exclaimed, heaving.

“Forty-six more seconds.” Brazil ran in place like he was treading water, looking back at her.

“Go on.”

“You sure?”

“Fly like the wind.” She rudely waved him on. “Damn it,” she bitched as her flip phone vibrated on the waistband of her running shorts.

She moved off the track, over to the bleachers, out of the way of hard-bodied people who made her insecure.

“West,” she answered.

“Virginia? It’s . . .” Hammer’s voice pushed through static.

“Chief Hammer?” West loudly said. “Hello?”