Sound

Authors: Sarah Drummond

First published 2016 by

FREMANTLE PRESS

25 Quarry Street, Fremantle WA 6160

Copyright © Sarah Drummond, 2016

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the

Copyright Act

, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

Editor Georgia Richter

Cover design Carolyn Brown

Cover photograph Sergey Sizov,

www.shutterstock.com

Printed by Everbest Printing Company, China

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Drummond, Sarah, 1970â

The sound / Sarah Drummond

ISBN: 9781925163773 (epub)

Sealers (persons)

â

Western Australia

â

History

â

Fiction

Women, Aboriginal Australian

â

Western Australia

â

History

â

Fiction

First contact with Europeans

â

Western Australia

â

Fiction

Dewey Number: A823

Fremantle Press is supported by the State Government through the Department of Culture and the Arts. Publication of this title was assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

For my mum, Carmelita O'Sullivan

K

ING

G

EORGE

S

OUND,

W

ESTERN

A

USTRALIA,

1827.

ING

G

EORGE

S

OUND

J

ANUARY

1827

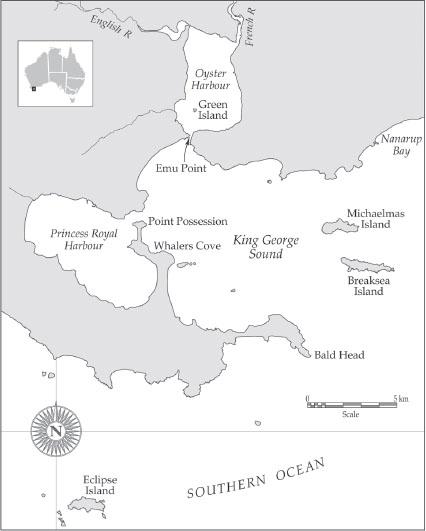

My name is Wiremu Heke. Some people call me Billhook. On this day, with the story I had to tell, the Major called me Mister Hook. I stood outside a canvas tent on a reedy foreshore in the cleavage of two mountains, from which grey plates of granite channelled water down to the inlet. There were no buildings here, no roads or even horses, only a few tents, the bush and a brig sitting out on the water. I was oceans away from my home and I was waiting to be interviewed about a murder.

Beside me a soldier jingled the keys to my handcuffs. My stomach felt sharp and tight. Golden light filtered through the tent, musty from the ship's hold. I stood at the flap, looking in. A young man stared out at me, like a child who has heard stories of savages and cannibals. Only his white man's stiffness stopped him from reaching out to touch the pounamu stretching my earlobe, or the huge, glossy teeth around my neck. The young man sniffed and touched his nostrils with soft fingers. From the set of his eyes and his jaw, he must have been the son of the man writing at the desk behind him.

“Sir,” the soldier said. “William Hook, sir.”

The Major twisted in his chair and I looked down to the frayed canvas feathering my feet. The Major had just shaved and his jowls gleamed. He stood, a straight man.

“Are you from the same gang as Samuel Bailey?”

“

Gov'nor Brisbane

sir, yes.”

“Where are you from, Mister Hook?”

From the little bay, where the eels are, near the marae, before the sand spit, before the open cliffs where the kelp surges like great black snakes in the swell.

“Aramoana. Otakau.”

“A native of the south island of New Zealand.” He sat and wrote. “MÄori.” His hand stayed on the paper and he looked at me. “The

Sophia

?”

Ae, they all know, these men under the banner of the King. They know who did the burning and the killing. My father on the beach, bleeding, his fleet of waka sawn in half by Kelly and his thugs. But those men don't know the smell of my charred Otakau. The work of a torch and a following wind.

The Major's grim smile made me want to turn and leave his stinking golden tent but there was the idling soldier, and there were things that I needed done.

“I was a boy sir.”

“Approximately twenty years of age.” The Major wrote on his paper again. He asked me questions and then the same questions again. He ran around my story of the killing and then around it again. The Major wrote all of the names down carefully. His son returned with sweet black tea in white cups and the tent grew warmer with its steam and our bodies and the climbing sun. Finally the Major dipped the end of a pen in ink, blotted it on rough paper and handed it to me.

“Sign please.”

I stared at the black lines tattooing the paper. “If I do this, then you will go to the island and rescue Tama Hine and Moennan.”

The Major sighed. “Your ⦠sort are called sea wolves and pirates and that is in polite society, Mister Hook. Worse down on the docks. Your crimes in King George Sound have created tremendous hardship for my men and myself. Your actions are â”

“I beg your pardon, sir. But will you get them from the island?”

“My pardon is the least of your concerns.” But he nodded. “First light. I intend to have Samuel Bailey arrested.”

I bent over the table and signed the paper.

X.

RAMOANA

1825

Wiremu Heke was newly a man when the chiefs called a public meeting about Captain Kelly and the

Sophia.

Wiremu's father limped along. He was too broken to work but the elders held him in high esteem. Eight years after the attack and the people still wanted revenge. Several young men needed to avenge fathers and mothers who had died from the bullets. It was part of their heritage and their right, they argued, to gather up honour, the way the white man gathers up medals and stripes.

They had to find the sea captain. For all the rumours and stories from visiting whalers, Kelly and the

Sophia

never returned to Whareakeake or Murdering Bay as the whalers called it. Wiremu's father knew of his son's hankerings and volunteered him to the sea and a seaman's life in search of information on the Captain's whereabouts. “Send young Wiremu. He is hungry for the ocean.” Wiremu was hungry for the girl Kiri too but the sea collected him up like a cuttlebone.

The chiefs ordered him and five other young men to work aboard the whalers, to collect crop seeds and knowledge from the shores of New South Wales, and find Captain Kelly. If they found him, they would entice him to return on a peace mission to Otakau where the chiefs would be waiting for him. No man explained to Wiremu how to garner a sea captain.

Life for this Otakau boy changed quickly after the meeting. A sealing schooner arrived and its captain offered to take him aboard as a mate to Van Diemen's Land, where he could then

work his way to the New South Wales colony. He had time to romance the girl but briefly, in a sweaty rush by the river. She had a knowing glint in her eye that he would leave soon. Kiri's breath whistled as she cried out, and later as she slept on the thatch mat he'd laid down for her, he watched her breathe. When she awoke, he asked her about her wheeze. She did not think of herself as unhealthy or ill. “Born on the river, Wiremu,” she said, stroking his face. “Born on the river.”

His father arranged for Wiremu to be tattooed. He squatted on the mat beside his son and talked as the tattooist worked. His father told him stories to distract him from the pain of the chisel. He talked and talked. It seemed rudderless talk until Wiremu realised he was talking his way into ancestral stories, carving them into Wiremu's memory while the tattooist carved the spirals into his flesh.

He told Wiremu how he came to build boats, the same boats Wiremu would paddle out beyond the heads to catch barracouta. He had learned his trade from his uncle who had learned from his grandfather. Wiremu's great-grandfather was first a boatbuilder, but when he was broken by his enemy's mere, he became a carver of wood and then a tohunga tÄ kaue, a carver of flesh.

Wiremu's great-grandfather had fallen in love with a Ngai Tahu girl. She was the daughter of a visiting chief. She wore a necklace of orca teeth. She saw Wiremu's great-grandfather carving into bartered kauri, on the edge of the river where he lived with his wife and son. She watched him carve the ocean into the wood with chisel and hammer. He may well have been using a leaf, his blows and strokes were so fine. He asked the wood politely to work for him. She saw that and she asked him, “Why don't you work it harder and it will be quicker?” He replied that he must ask or the ocean would be lost. It was a mere he was

carving and as he smoothed his hand over the wood, he thought that one day it may kill a man or break him, and his blood would fall over the earth like resin. Only when she said she had sought him out because she was told he could give her moko, did he look up at the girl.