Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 (4 page)

Read Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 Online

Authors: Philip A. Kuhn

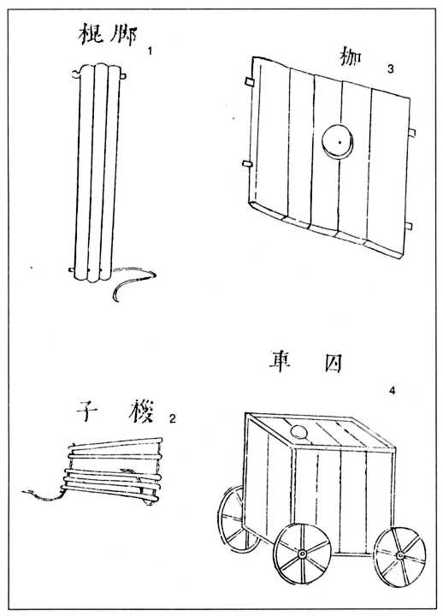

"The ankle-press at work.

Various authorized torture ("punishment") implements:

(i) the ankle-press;

(2) a device for squeezing the fingers;

(3) the cangue;

(4) a prisoner transfer cart.

Ever since their first encounter with the Hsiao-shan authorities,

Cheng-i and Ch'ao-fan had stubbornly clung to the story that constable Ts'ai had arrested them falsely, because they had refused him

money. This was a story common enough in local society. Yet who

would believe these ragged monks? Could the public hysteria about

sorcery be wholly groundless? And what of the concrete evidence

Ts'ai had produced from Chu-ch'eng's baggage? At neither the

county nor the prefectural level were the monks believed. Now the

provincial judge, Tseng Jih-li, pursued the same line of questioning:

Judge Tseng: Chu-ch'eng, you're a beggar-monk, so you naturally have

to beg for your vegetarian food. But how come you had to ask the

name of someone's child? This is crystal-clear proof of your soulstealing. When you made your first confession here, you wouldn't

admit that you had asked the child's name.

Chu-ch'eng: ... That day, at the county yamen, I said I had asked his

name, so the magistrate kept asking about soulstealing. The attendants gave me the chia-kun three times, and my legs still haven't

healed. I was really scared, so when I arrived here and Your Excellencies questioned me, I didn't dare say anything about asking the

kid's name ...

Judge Tseng: ... If there wasn't solid proof that you did these things,

how come the crowd was so angry that they wanted to burn you or

drown you?

Chu-ch'eng: . . . When they saw the parents had grabbed us, they all

suspected we were soulstealers, so they shouted about burning and

drowning us. Really, that was all just guff. Later, when the headman

took us to the post station, the crowd all went away ...

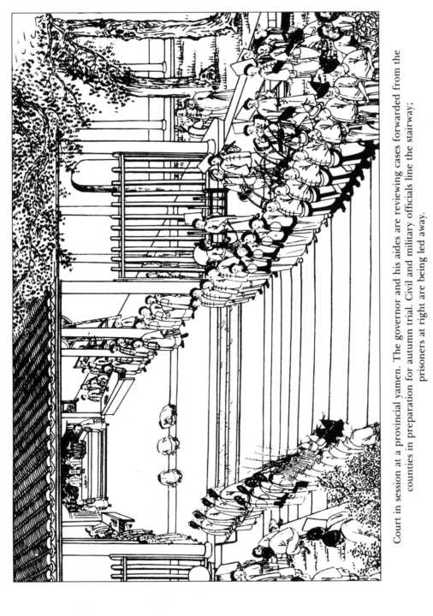

Officials at the grand provincial yamen were apparently less

inclined to coddle police underlings than were officials at the county,

who depended on the likes of constable Ts'ai to carry on their daily

business. As the prisoners cowered before the provincial judge,

Cheng-i repeated his tale of attempted extortion. Ts'ai Jui, he

insisted, had told them that day in the temple that he had been

ordered to arrest "vagrant monks" and would let them off only if

they paid him the "customary fee." Cheng-i had answered, "We're

beggar monks. Where are we going to get money to pay you?"

Something about Cheng-i's story struck judge Tseng as plausible.

Men like constable Ts'ai were not professional police, but belonged to the general category of local underlings known as "government

runners" (ya-i). They performed many distasteful and demeaning

local jobs such as torturing suspects, serving summonses, "urging"

the payment of taxes, and running miscellaneous errands around the

government offices. Those who, like Ts'ai, did police work were

considered to be of "mean" status and not permitted to sit for civilservice examinations. They were paid little and had to support themselves by demanding "customary fees" from all commoners whom

they dealt with. Some "runners" were not even on the official rolls,

but were destitute men who had attached themselves as supernumeraries to others. These received no pay at all and simply preyed

upon the public. It was commonly said that runners were a low lot

and had to be kept in check, yet few officials could do so because the

runners' services could not be dispensed with.16

Now constable Ts'ai was brought forward and made to kneel.

Though Judge Tseng probed at his story, Ts'ai clung firmly to it,

and was left kneeling for the rest of the day. At last the exhausted

man realized that the game was up. Indeed, he now confessed, he

had demanded cash. When the monks balked, he proceeded to search

their baggage: "Where did these things come from? Now if you don't

fork over several strings of cash, I'll take you to the county and say

you're queue-clippers."

With the discovery of the compromising scissors and queue-binder,

the stakes rose. As the shouting match grew louder, the inevitable

crowd gathered. Amid the hysteria, Ts'ai sensed more trouble than

he could handle. He persuaded the crowd to disperse by arresting

Cheng-i and dragging him off. Instead of taking him directly to the

county yamen, however, he brought him and the incriminating baggage to his own home, located in a blind alley which backed onto the

city wall. He was followed by the irate Ch'ao-fan, who demanded his

traveling box. "I'll give it to you only if you bring in those two other

monks," said Ts'ai. Ch'ao-fan, fuming, set off for the yamen to

protest.

Constable Ts'ai's confession went on. Once safely in his own house

with the chained Cheng-i, he said, "Now that everyone's gone, just

cough up a few strings of cash, and I'll be glad to let you escape."

But the outraged monk insisted that he was going to file an official

complaint. Ts'ai started beating him, but without result. He realized

that he was in serious trouble unless he could make the queueclipping charge stick. Unfortunately, there was only one lock of hair in Chu-ch'eng's box; furthermore, it was straight hair and did not

really resemble a clipped queue-end. So Ts'ai found an old lock of

hair in his own house, went out in the alley where Cheng-i could not

see him, and carefully braided it. For a bit more evidence, he cut

some strands of fiber from his own hat fringe and braided them up

to resemble two little queues. This hastily concocted evidence he

placed in the monk's traveling box along with his own pair of scissors

(making a total of four), and marched his prisoner off to the magistrate's yamen.

There, even under torture, Cheng-i clung to his extortion story.

But the magistrate sagely pointed out that there was obviously no

bad blood between constable Ts'ai and Cheng-i, the two being total

strangers, so Ts'ai could have had no motive for framing him. On

this basis, the case had gone up through the prefectural court without

being suspected.

Now that Ts'ai had confessed to the frame-up, however, judge

Tseng turned the case back to the Hsiao-shan County authorities.

The constable was beaten, exposed in the cangue, and finally let goperhaps a more circumspect guardian of public order. The monks

were freed, each with 3,200 cash to sustain him while his broken

bones healed.

Popular hysteria and petty corruption had nearly resulted in a

serious judicial error. Courtroom torture had elicited confessions, but

these were compromised by the accuseds' complaints before higher

authorities. Once the case reached the provincial level, the bias

against the accused was balanced by the worldly-wise skepticism of

high officials far removed from the pressures and temptations of

grubby county courtrooms. A case of sorcery? More likely, the usual

nuisance of a credulous rabble abetted by greedy local police ruffians

and incompetent county authorities: a case the province was now

happily rid of.

Yet the tide of public fear was stronger than judge Tseng and his

colleagues knew. The same day that Chu-ch'eng and his friends were

arrested, persons elsewhere in Hsiao-shan had beaten an itinerant

tinker to death because they believed that two charms found on him

were soulstealing spells. Officials later discovered that they were conventional formulae for propitiating the Earth deity. The unlucky

tinker had been carrying them while cutting trees in his ancestral

cemetery. A week earlier in An-chi County, which bordered Tech'ing, the epicenter of sorcery fears, an unidentified stranger with an unfamiliar accent had been roped to a tree and beaten to death

by villagers on suspicion of soulstealing."

Within a fortnight, rumors of soulstealing in Chekiang had spread

to Kiangsu. Soulstealing (by the queue-clipping method) was believed

to be practiced by itinerant beggar-monks from Chekiang, who were

entering the neighboring province to practice their loathsome craft.

The local authorities were alerted. Likely suspects were quickly

found.

The Beggars of Soochow

In Soochow, an ornament of China's most elegant urban culture, seat

of the governor of Kiangsu, China's richest province, on May 3, 1768,

local constables seized an old beggar of "suspicious" appearance. The

charge was clipping queues for the purpose of soulstealing.'s Local

authorities did not, however, allege an association between queueclipping sorcery and the political symbolism of the queue.

The ragged creature who was dragged into the constabulary on

that May morning was Ch'iu Yung-nien, a native of Soochow Prefecture. Ch'iu, fifty-eight, was an unemployed cook who had turned to

begging "along the creeks and rivers." By April 26, his wanderings

had brought him to Ch'ang-shu, a county seat just south of the

Yangtze, where he took lodgings at a rooming house. There he met

two unemployed men who, like him, had taken to the road in order

to survive: Ch'en Han-ju, twenty-six, an unemployed "maker of dusters and hat fringes," whose home was Soochow; and Chang Yuch'eng, forty-one, formerly a peddler of dried salt fish. Chang was

the only one from outside the province, having wandered all the way

from Shao-hsing, Chekiang (a journey of i 20 miles along the Grand

Canal). These three marginal men, cast off by the "prosperous age"

of the mid-Ch'ing, found that they were all heading south toward

Soochow, and on May 2 set out together.

By the next day they had reached Lu-mu, a teeming commercial

district north of the Soochow city wall, on the banks of the Grand

Canal. While his companions begged in a pawnshop, Ch'iu squatted

by the roadside. There he was seized by constables from the Soochow

garrison, accompanied by two constables from the Ch'ang-chou

County yamen. He was found to be carrying a knife and some paper

charms. As the constables questioned him, a crowd gathered. Among

the bystanders was a ten-year-old boy, Ku Chen-nan, who told anyone who would listen that earlier the same day he had felt his queue

tugged, but could not see who had done it. That was enough for the

police. Beggars Chang and Ch'en were quickly found and imprisoned

with Ch'iu. The three were tortured with the chia-kun in the usual

manner. Confronted with the incriminating evidence found on him,

Ch'iu insisted that the knife was for making "orchid-flower beans"

for sale. The paper charms (each imprinted with "great peace," t'aip'ing) he would paste on doorways in the market streets and then ask

for handouts. All three steadfastly denied the crime of queue-clipping. The boy, brought in and questioned, repeated his story:

I'm ten years old and I study at the County Academy. On the third of

May, as I was going home, walking north, someone gave my queue a

yank from behind. I turned right around, saw someone running away.

My queue had not been cut. Later I was told that the constables' post

had arrested some men and I was ordered to go there and identify

them. When it happened, I was walking along and the person was

behind me. I couldn't see his face. The man wearing black here, Ch'en

Han ju, looks sort of like that person, but I can't identify him for sure.