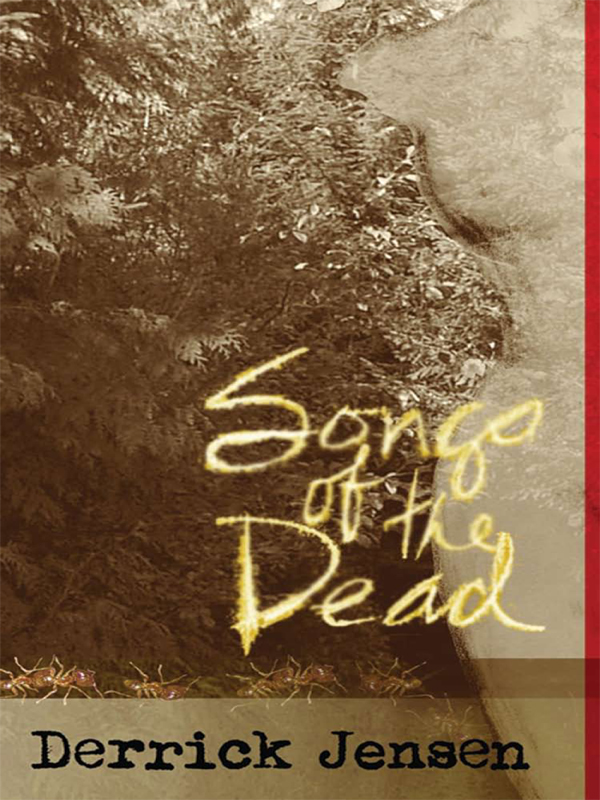

Songs of the Dead

Authors: Derrick Jensen

Tags: #Fiction, #FIC000000, #Political, #Psychological, #Thrillers, #General

Songs of the Dead

Derrick Jensen

Flashpoint Press

An imprint of PM Press

© 2009 Derrick Jensen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electric, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Cover design by Beth Orduna and John Yates

Text design by Michael Link

Edited by Theresa Noll

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-1-60486-044-3

LCCN: 2008934204

Jensen, Derrick, 1960â

Songs of the Dead / by Derrick Jensen.

p. cm.

Fiction

Flashpoint Press

Published by PM Press

Flashpoint Press Box 903 Crescent City, CA 95531

www.flashpointpress.com

PM Press Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623

http://www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper.

Also by Derrick Jensen

Lives Less Valuable

What We Leave Behind

How Shall I Live My Life?:

On Liberating the Earth from Civilization

Now This War Has Two Sides (double CD)

As the World Burns:

50 Simple Things You Can Do to Stay In Denial

Thought to Exist in the Wild:

Awakening from the Nightmare of Zoos

Endgame Volume I:

The Problem of Civilization

Endgame Volume II:

Resistance

Welcome to the Machine

The Other Side of Darkness (triple CD)

Walking on Water

Strangely Like War

The Culture of Make Believe

Standup Tragedy (double CD)

A Language Older Than Words

Listening to the Land

Railroads and Clearcuts

Songs of the Dead

Derrick Jensen

Table of Contents

That we come to this earth to live is untrue:

we come but to sleep, to dream.

Aztec Poem

Each night, I walk the line that wends between unconsciousness and terror, between forgetting and remembering, between present and past. Each night I do not fall asleep but instead stumble through time, falling into deep impressionsâlike five-pointed hand-prints on soft clayâof past on present, living in house after house after house of imagination, each one an edifice of events uncompleted. Does the land dream so, too, carrying with it the weight of thousands of years of nights on nights, remembering salmon that were and are not, caressing them in the infancy of their evolution and caring for them in their absence? Does the land mourn these losses as I mourn my own, and does sheâit, he, pieces of moist soil between my fingertips, the orange bellies of ponderosa pine four arm lengths aroundâdream as well of times unwounded, and of woundings? Does time wind and unwind for herâfor I know now it is herâeach night as she sleeps beneath snow, stars, cold wind, trees sighing sadly or giving up their own ghosts before meeting what we have become, beneath a moon that night after night sees all, yet keeps remembering?

I know now that there is and always has been a heart that beats beyond the grasping of our mechanical fingers, unfound in the claws of our braced backhoes, slipping away in the face of our too-coarse bulldozers. The past resides in the soil, and though we believe it blows away and is lost, that is not true. It is there all the time, though we do not see it.

Our dreams carry with them the perfume of this soil, and will not without a fight let go of that which beneath it all makes each of us who we are. So each night I walk that fine line, and sometimes awaken to freeze before all that has happened to me, to her, to each of us, and to wish that things could be different than they are.

He touches the still-warm skin of her belly with the first three fingers of his left hand. Almost on their own, his fingers trace tiny circles toward the tented skin over her pelvis. Her skin is soft, pale. Her scent fills the room.

He stands between her legs, leans over slightly, then more. He touches the scalpel in his right hand to the skin just below her navel, and draws a line to her pubic hair, pink of skin, thin white layer of subcutaneous fat, light brown layerâso thinâof muscle, then the yellow wall of the abdominal cavity itself. The geology of skin. Which layer came first?

He remembers how she was a short time ago, still breathing, gasping, clinging tight to whatever she could grasp. Her clawed fingers opening and closing, wrists twisting beneath metal holding her to the table, skin tearing, and beneath the skin muscles tightening, rising up, trying to leave her body.

Dying, she'd terrorized him more than ever before. Again and again he'd asked her the one simple question he always asked, and again and again she'd pretended not to know. She'd kept up that feigned ignorance to the end, when with her last wordsâmore a sigh, really, a gurgle, a retch, than any sort of sentenceâshe'd been able to convince him her ignorance might be real. “Nothing, nothing. Not at all.” That's what she had said.

The scalpel. So small. Sharp. Bright. He breaks into the peritoneum. The first time he had done that he'd been surprised there was no stench. Some animals stink when you open them up. Most people don't. He sees the intestines, long tubes sheathed in fat, lifts them up and sees the bladder. It's also white. So much white. The size of a fist. Beneath that, what he's looking for. Pale pink, white, another fist. He slices at the ligaments, then pulls at the uterus. It doesn't come out easily. It never does. He reaches behind and beneath to sever the attachments, and finally the organ is liberated. He brings with it the ovaries.

His fingers are red. Cherry. Burgundy. Darker. Almost black. He looks at his watch. It's late. He puts down the scalpel.

This time he burns the body. He puts it in the back of his pickup and takes it south of town. It rides wrapped in blue plastic beneath the shell. The ride is smooth until near the end, when he drives across railroad tracks, up a slope, around a corner, and into a small quarry. Fractured rock on three sides, and trees on the other.

Good cover. Here he can watch, just a little. He wants to see the fire. He's never done that before.

He stops the truck, hears the click of his door opening and the soft catch as he slowly shuts it. Walking to the back of the truck, he hears the gravel grind beneath his feet. He opens the shell and rear gate, then reaches for the tail of the blue tarp and pulls it toward him. The tarp is heavy, but not so heavy that he isn't able to carry it.

Then the unwrapping. He rolls the body free of the tarp, but doesn't look at it until he returns from the truck with the gasoline. Now he looks at her. Dark blonde hair, soft, tangled. Pockmarks on her face. Missing a tooth. That wasn't his doing. It was already gone.

She was not a pretty woman, he thinks, not very pretty at all. But at one time she had been. She'd had a picture in her wallet of a younger woman, standing next to a man. The woman was beautiful: slender, long blonde hair, smooth skin. He had asked her who that was, and she'd said it was her. “What happened?” he'd asked.

She hadn't answered, but she hadn't needed to. He'd known the answer. He'd seen the tracks on her arms when he first picked her up. Scabby, scarred, bruised. Abuse, drugs, alcohol, and sunlight had all worked together to harden the muscles of her face until she could no longer remove the mask of impassivity that protected her from customers, and from everyone. Or almost everyone.

He pours the gasoline, sets the near-empty gas can a safe distance away, lights a match, then uses it to ignite a twisted piece of newspaper. The flame describes a soft arc toward the body, then flashes outward in a concussive wave he feels in his belly. For a short time the flames seem to hold themselves above the body, but as he watches the skin begins to darken, then split away from the muscles tightening and becoming dark themselves, braiding to look like nothing so much as jerked meat. He follows the smoke up and realizes he needs to leave. Too much smoke, more than he anticipated. Someone could see. Still not too worried, though, he watches a few more moments before retreating to the truck, and afterwards driving back to the highway, back to the town.

For the past few years, I've been working on a book called

Possession

. It is, like all of my other books, an attempt to provide at least preliminary answers to what I perceive are some pressing questions.

A Language Older Than Words

, for example, is, among other things, an attempt to explore the relationships between silencing and atrocity, and between remembering and healing. In

The Culture of

Make Believe

I wanted to ask and attempt to answer questions like, What is hate? What are the relationships between hatred, perceived entitlement, objectification, and atrocity? What are the logical endpoints of this culture's way of perceiving and being in the world? And

Endgame

was centered around the questions, Do you believe this culture will undergo a voluntary transformation to a sane and sustainable way of living? If not (and almost no one I ever talk to believes it will) what does that mean for your strategy and tactics to defend the places you love?

It's always easier to articulate the questions that drive a book long after that book is done. During the writing itself, it often seems as though I'm slowly feeling my way forward in the dark, arms outstretched in front of me to warn of obstacles, as I attempt to follow some almost entirely unseen path toward some entirely unseen goal. Often this goal is not only unseen, but literally unimaginedâthat is, after all, one of the points of writing a book: to imagine and articulate that which before, you could not put words to or sometimes even conceptualizeâbut it feels like

Possession

is yet another attempt to understand the incomprehensible destructiveness of this culture. We can talk all we want about silencing, perceived entitlement, and all that, but none of it could ever be sufficient to explain how any group of people, no matter how stupid or arrogant, could kill the planet they live on so that they can make money.

Possession

is about more than that, though. It's also about our relationships to various parts of the world about us. And this is where

Possession

veers slightly away from the other books; in this book, far more than in the others, I ask about our relationshipsâsometimes beneficial, sometimes harmful, sometimes neither, sometimes bothânot only with those others we can see and feel and hear, like trees and dogs and cats and rivers, stars, mountains, and so on, but even moreso with those we can't: muses, fates, the dead, and so many others. Asking these questions is then leading me, shuffling as always and sometimes stumbling, toward questions concerning free will, or put more straight, toward questions about how I make decisions, or put straighter still, toward the question: when I do make a decision, who is making that decision? Who's in charge? And further, whoâchance, physics, fates, God, the gods, or any (and maybe all) of a myriad of othersâ determines the results of that decision?