Something Red (37 page)

They swung along, through oakwood rich in wood sorrel and wood anemone; this gave way to ash forest with its ground cover of bluebells, and primrose whose leaves Molly used in some of her wound-healing salves, and wild garlic. Red squirrels scampered through the branches; the air was alive with birdsong, blackbirds and mistle thrush predominating; and over all was the scent of fresh breezes, green life, sun-warmed earth: forest delights after so many days cooped up indoors.

After a while Jack leaped down from the wagon seat and stretched; he threw the reins over the mare’s head and walked ahead, using the reins as a lead. As Hob trudged forward, he kept his eyes on Jack, walking in front. For a time Jack walked along with his gaze on the ground in front of his feet, but after a while his pace picked up; he looked about; he breathed deep of the clear air. He straightened, and despite the slight limp left him from his crushed ankle on that day, so long ago, when his Fate came bounding out at him from a seething cloud of sand, he began to fall into a marching rhythm, and now for just a moment Hob could see him as a younger man, as the soldier he had been, trudging stolidly down the long and dusty road to Jerusalem.

At a pass where the road began its descent to the eastern coast and the roads to Durham and York, the escort halted, the knights backing their mounts to the side of the road and saluting as Molly and her troupe passed them. Hob looked back a few times, and the knights remained motionless, till they had dwindled to specks, a courtesy: watching over them as long as possible.

A

LL THE REST OF THAT DAY

they wound down out of the hills at the familiar plodding pace, dropping down toward the moorlands, the wind from the fells rising to meet them. Jack was up on the wagon seat again, he and Molly and Nemain working the brakes, and Hob trying to keep Milo from wandering onto the downslopes at the side of the path. Blocks of worn diabase formed giant steps down which cold gray streams poured, foaming into white at each successive level. Cool mist hung over the downrushing water, and drifted over them whenever the wind shifted their way, wetting Hob’s garments, forming a sheen on Milo’s hide.

Molly had elected to keep her original configuration of animals, rather than accept the offers of horses and gold and an escort and such

that Sir Jehan had wanted to press on them. She had seen some signs—in the flight of crows, in the movement of dark rain-heavy clouds—that she had interpreted as guidance from her patron Babd, telling her that she must remain as inconspicuous as possible for a bit longer. Nemain teased her about this, pointing out that Molly was noticed wherever she went, but Molly was adamant.

“And at any road, we’ll be back in Blanchefontaine this fall, when the weather begins to turn, for Sir Jehan must have care just as Jack must have care, lest he find himself howling at the moon, and changing to a Fox, and what then? Mayhap being burnt alive by the Church.”

“Does he know his peril, Mistress?” Hob asked.

“Aye, he is well aware of this—and that being one other reason for him to be our staunch ally, and like to be a great help when we return to Erin. And you, young man,” she said to Hob, “he has said he will make a rider of you, and help you win belt and spurs: for Sir Balthasar’s after telling him he sees something in you that he sees in few others, and that a fine knight in the Norman style might be made of yourself. And if so, so much the better for yourself, and for ourselves and our hope to return to Erin.”

For now Hob was content with the sun on his face and the road before him, and the wheels rumbling along, bearing the little troupe into an uncertain but promising future.

M

OLLY CHOSE A SPOT

on the slope of a hill crowned with a copse of trees; a common sight in Britain, where wooded hills served as sacred groves for sacrifices, before the coming of Christ. They pitched camp just below the trees. Jack busied himself clearing a place for a campfire, and gathering wood for it.

A stream ran down out of the grove to the meadow below. Where

it passed the camp, though, it was choked with rushes and soggy leaves from last fall. There was no way to bring the wagons into the wood. Molly sent Hob with a bucket to follow the stream up the hill, into the trees, to obtain cleaner water from the source.

Somewhat to his surprise, Nemain trailed after him. Up and up they made their way, in the dim aisles between the trees, through fern and violet, following the lively gurgle of the brook as it rushed downhill past them. A last push through vines and wood anemone and herb Paris, and they came upon a little clearing where the space between trees was somewhat greater.

There a spring welled up into a natural rock basin of no great size. The water in the basin was clear as air, and Hob could see the several sources of the spring as disturbances in the water, bubbling up through the smooth gray stones on the bottom. The irregular bowl was constantly spilling from the lower, downhill side of its lip, silver sheets splashing out and away down the hillside in the stream they had followed here. It was as beautiful in its rough way as the formal white-marble fountain of which Sir Jehan was so proud.

Nemain knelt beside the spring and drank from her cupped palm. Hob watched her, the curve of her back as she bent over the water, and it came to him that she had gained some weight during the spring, and her face was a little fuller; it was softer and prettier than it had been; and her skin had long since cleared. There was a curving width to the once-narrow hips, no longer much like a boy’s, and a slight but distinct swell to her bosom.

Nemain stood and retreated a pace or two, wiping her lips on her sleeve. She leaned back against a tree, and the dappled light fell across her. This time Hob was not behindhand: he set the bucket down with a muffled bump, took two strides toward her, and put a hand on the curve of her hip. She looked up at him, that look he had seen before,

enigmatic, challenging. Green eyes, green eyes! He raised his hands and placed them gently to either side of her face, as someone had taught him once, so long ago, and kissed her full on the mouth.

She threw her arms about his neck, and kissed him back with an ardor that surprised him. “Hob,” she said, and gripped his shoulders. She hesitated a moment, distracted by the new musculature beneath her hands.

“Hob—Robert, Herself was in the right,” she said. “She’s just after seeing you in the priest house, and she tells me, ‘That’s your man-to-be,’ and you a wee boy, so that I laughed.”

“Herself said—” Hob began, dazed, happy.

“But after a time I was no longer laughing, and I knew it also, that you should be my man, and I not needing yarrow under my pillow come Midsummer Eve, that I might have a dream of my future consort.”

She kissed him again, with a kind of ferocity, and the mention of yarrow that had put him in mind of last summer’s camp slipped away, his arms full of her warm body and her face so close to his, so that what he remembered was not the yarrow but the glade where he drew water for that other camp, and how her green gaze reminded him of that deep fern-shaded pool, and how her hair was like the tumble of wild roses down the water’s bank in that glade, and how her face was the white of lilies.

“Nemain,” he said simply, and then found that he could say no more; then he thought that there was no more that he need say.

“And next year,” she said, “it’s you and I, Robert, will be clasping hands over a stream, and swearing to one another, and then you will be my consort for aye.” And after the next kiss she slipped from his arms, and said, “Are you ever going to fill us that bucket?”

She walked away laughing, with some of the mockery that he knew so well from Nemain the little girl, but she turned and looked at him over her shoulder, and it was not a little girl’s look; and she was no longer

the scrambling child he remembered: she moved as a lynx moves, with a dangerous grace.

She was away and down the hill before he could rouse himself to dip the bucket into the rock basin. He set off down the hill, the weight of the water unnoticed, because of either his new strength or the exalted singing of his blood. He came out from the shelter of the trees in time to see her climb into the small wagon, and he stopped.

He stood there for a long time. He could just barely make her out through the open window as she moved about within, busy, perhaps, preparing one of Molly’s mysterious remedies. He took a fine deep breath. He had the sense that the ground had shifted underneath his feet, and that he saw his life from a new vantage point: it was like looking down on the hawks by Monastery Mount, instead of up at them.

Later, when he was a man of property and power in Ireland, and a queen’s consort as well, Hob could still recall unaltered this moment, this fragment of life in which his time-to-come stood forth and revealed itself to him.

The world seemed to widen, rippling outward from where he stood, and the air to take on a luster, so that the sunlight playing in among the clouds of leaves bore a brilliant clarity he had never before encountered. The wind twirled the leaves on their stems; the alternating surfaces, green above and silver beneath, twinkled before him. Within all this woodland glory was set the wagon like a jewel box, and within the wagon Nemain, that jewel, moved back and forth across the window. And this was all his.

He thought that he almost remembered this scene, and all this beauty, from another time, or from another campsite, or from a dream: her bare forearm as she reached for the wagon’s high shelves, that quick gleam of white skin; and her hair swinging forward to hide her features as she bent to her work, that flicker of something red.

GLOSSARY OF IRISH TERMS

a chuisle | pulse, heartbeat (“O pulse”) |

a rún | love, dear (“secret treasure”) |

Mavourneen | my sweetheart ( |

mo chroí | my heart |

mo mhíle stór | my thousand treasures |

seanmháthair | grandmother (literally: “old mother”) |

stór mo chroí | treasure of my heart |

uisce beatha | whiskey (“water of life”) |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank my editor, Emily Bestler, for her enthusiasm for this book, and for her intelligence and good cheer. I am grateful to my agent, the excellent George Hiltzik, a man who gets things done. My gratitude also to dear friends Patricia and Michael Sovern for their support of this project, and, always, the pleasure of their company. My thanks to Susan Holt, for her unfailing advocacy and encouragement; to Polly Pen, Susan Blommaert, and Craig Every for their kind and helpful comments; to Juosef Natangas Tysliava for help with the pronunciation of Lithuanian names; and, for her sharp eye and shrewd advice and heartening words, to the First Reader and Fairy Bride, Theresa Adinolfi Nicholas.

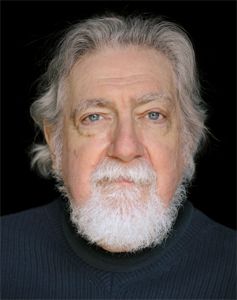

DOUGLAS NICHOLAS

is an award-winning poet whose work has appeared in numerous publications, among them

Atlanta Review, Southern Poetry Review, Sonora Review, Circumference, A Different Drummer,

and

Cumberland Review,

as well as

South Coast Poetry Journal,

where he won a prize in that publication’s Fifth Annual Poetry Contest. Other awards include Honorable Mention in the Robinson Jeffers Tor House Foundation 2003 Prize for Poetry Awards, second place in the 2002 Allen Ginsberg Poetry Awards from PCCC, International Merit Award in

Atlanta Review

’s Poetry 2002 competition, finalist in the 1996 Emily Dickinson Award in Poetry competition, honorable mention in the 1992 Scottish International Open Poetry Competition, first prize in the journal

Lake Effect

’s Sixth Annual Poetry Contest, first prize in poetry in the 1990 Roberts Writing Awards, and finalist in the Roberts short fiction division. He was also recipient of an award in the 1990 International Poetry Contest sponsored by the Arvon Foundation in Lancashire, England, and a Cecil B. Hackney Literary Award for poetry from Birmingham-Southern College. He is the author of

Iron Rose,

a collection of poems inspired by and set in New York City;

The Old Language,

reflections on the company of animals;

The Rescue Artist,

poems about his wife and their long marriage; and

In the Long-Cold Forges of the Earth,

a wide-ranging collection of poems. He lives in the Hudson Valley with his wife, Theresa, and their Yorkshire terrier, Tristan.

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

www.SimonandSchuster.com

• THE SOURCE FOR READING GROUPS •