Someday, Someday, Maybe (2 page)

Read Someday, Someday, Maybe Online

Authors: Lauren Graham

Tags: #Romance, #Humorous, #General, #Contemporary Women, #Fiction

“It’s kind of cold in here, you know,” Dan announces, scrutinizing the room from beneath his long brown bangs. Dan always needs a haircut.

“Dan,” I say, sitting up, pulling the covers to my ears, “I have to tell you—this flair for the obvious? Combined with your shoe-throwing accuracy? You should submit yourself to the front desk at The Plaza Hotel or something, and start a personal wake-up service. New Yorkers

need

you. I’m not kidding.”

Dan knits his brow for a moment, as if concerned he might actually be called upon to present his qualifications for the job, but then a little light comes into his eyes. “Aha,” he says, pointing his forefinger and thumb at me, play-pistol style. “You’re joking.”

“Um, yes,” I say, pulling an arm out of my blanket cocoon to play-pistol him back. “I’m joking.”

“Did you know, Franny,” Dan begins, in a bland professorial tone, and I steel myself in anticipation of the inevitable boring lecture to come, “the statue in front of The Plaza is of Pomona, the Roman goddess of the orchards? ‘Abundance,’ I believe it’s called.” Pleased with his unsolicited art history lesson, Dan squints a little and rocks back on his heels.

I stifle a yawn. “You don’t say, Dan. ‘Abundance’? That’s the name of the bronze topless lady sculpture on top of the fountain?”

“Yes. ‘Abundance.’ I’m sure of it now. Everett did a comprehensive study on the historically relevant figurative nude sculptures of Manhattan while we were at Princeton. Actually,” he says, lowering his voice conspiratorially, “the paper was considered rather

provocative

.” He pumps his eyebrows up and down in a way that makes me fear his next words might be “hubba-hubba.”

Dan and Everett, engaged to be married. Dan and Everett, and their mutual interest in the historically relevant figurative nudes of Manhattan. Apparently, that’s the kind of shared passion that tells two people they should spend the rest of their lives together, but you wouldn’t know it to see them in person. To me, they seem more like lab colleagues who respect each other’s research than two people in love.

“That

is

fascinating, Dan. I’ll make a note of it in my diary. Say, if it’s not too much trouble, would you mind checking the clock on the landing and telling me the actual time?”

“Certainly,” he says, with a formal little half-bow, as if he’s some sort of manservant from ye olden times. He ducks out of the room for a moment, then sticks his head back in. “It is ten thirty-three, exactly.”

Something about the time causes my heart to jump, and I have to swallow a sense of foreboding, a feeling that I’m late for something. But my shift at the comedy club where I waitress doesn’t start until three thirty. I had intended to get up earlier, but there’s nothing I’m actually late for, nothing I’m missing. Nothing I can think of, anyway.

“You know, Franny—just a thought,” Dan says solemnly. “In the future, if you put the alarm clock right by your bed, you might be able to hear it better.”

“Thanks, Dan,” I say, stifling a giggle. “Maybe tomorrow I’ll give that a try.”

He starts to leave, but then turns back, again hesitating in the doorway.

“Yes, Dan?”

“It’s six months from today, right?” he says, then smiles. “I’d like to be the first to wish you luck. I have no doubt you’ll be a great success.” And then he does his little half-bow again, and plods away in his size-fourteen Adidas flip-flops.

I flop back on my pillow, and for a blissful moment, my head is full of nothing at all.

But then it comes rushing back to me.

What day it is.

The reason I asked Dan to make sure I was up.

Why I’m having audition anxiety dreams.

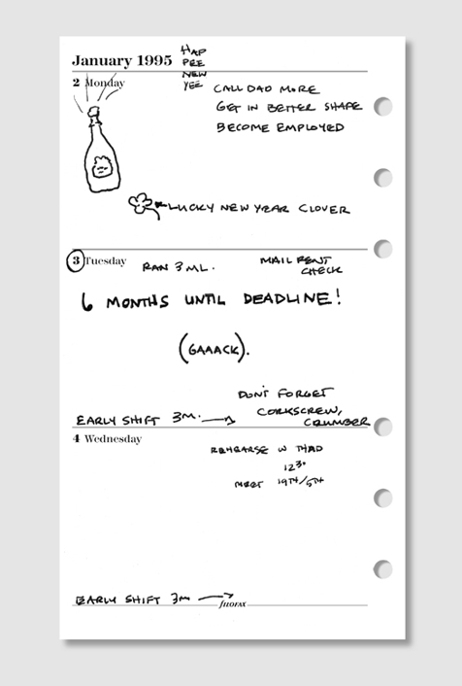

A wave of dread crashes over me as I remember: when I looked at the year-at-a-glance calendar in my brown leather Filofax last night, I realized that, as of today, there are exactly six months left on the deal I made with myself when I first came to New York—that I’d see what I could accomplish in three years, but if I wasn’t well on my way to having a real career as an actor by then, I absolutely, positively wouldn’t keep at it after that. Just last night I’d promised myself that I’d get up early, memorize a sonnet, take in a matinee of an edgy foreign film. I’d do something,

anything

, to better myself, to try as hard as I could to

not fail

.

I throw off my covers, now welcoming the shock of the cold. I have to wake up, have to get up, get dressed, for … well, I don’t know for what exactly yet. I could go running … running—yes!—I have time before work, and I’m already in sweatpants, so I don’t even have to change. I trade the fuzzy pull-on slipper-socks I slept in for a pair of athletic socks I find in the back of my top drawer, and I tug on the one Reebok that’s lying on the floor. I’m going to run every day from now on, I think to myself as I wriggle on my stomach, one arm swallowed beneath the bed, fishing blindly for the second shoe. I realize there’s no direct line between running this morning and reaching any of my goals in the next six months—I don’t think I’ve ever heard Meryl Streep attribute her success as an actor to her stellar cardiovascular health—but since no one’s likely to give me an acting job today, and there probably won’t be one tomorrow either, I have to do something besides sit around and wait.

And I’m not going to break my deadline the way I’ve seen some people do. You start out with a three-year goal, which then becomes a five-year goal, and before you know it you’re still calling yourself an actor, but most days you’re being assigned a locker outside the cafeteria of the General Electric building so you can change into a borrowed pink polyester lunch-lady uniform and serve lukewarm lasagna to a bunch of businessmen who call you “Excuse me.”

I’ve made some progress, but not enough to tell me for sure that I’m doing the right thing with my life. It took most of the first year just to get the coveted waitressing job at the comedy club, The Very Funny, where I finally started making enough in tips to pay my own rent without any help from my father. Last year, after sending head shots month after month to everyone in the

Ross Reports

, I got signed by the Brill Agency. But they only handle commercials, and it’s erratic—sometimes I have no auditions for weeks at a time. This year, I got accepted into John Stavros’s acting class, which is considered one of the best in the city. But when I moved to New York, I envisioned myself starting out in experimental theaters, maybe even working Off Broadway, not rubbing my temples pretending I need pain relief from the tension headache caused by my stressful office job. And one accomplishment a year wasn’t exactly what I had in mind.

Still wedged halfway beneath the bed, it takes all my strength to push a barely used Rollerblade out of the way. At this point, I’m just sweeping my arm back and forth, making the same movement under my bed as I would if making a snow angel, only the accumulated junk is a lot harder to move. I give up for a moment, resting my cheek against the cool wooden floor with a sigh.

“Do you have any idea how few actors make it?” people always say. “You need a backup plan.” I don’t like to think about it—the only thing I’ve ever wanted to be is an actor—but I do have one, just in case: to become a teacher like my dad, and to marry my college boyfriend, Clark. It’s not a terrible scenario on either count—my dad makes teaching high school English look at least vaguely appealing, and if I can’t achieve my dream here, well, I guess I can picture myself having a happy normal life with Clark, living in the suburbs, where he’s a lawyer and I do, well, something all day.

I played the lead in lots of plays in high school and college, but I can’t exactly walk around New York saying: “I know there’s nothing on my résumé, but you should’ve seen me in

Hello, Dolly!

” I suppose I could ask one of the few working actors in class, like James Franklin, if he has any advice for me—he’s shooting a movie with Arturo DeNucci, and has another part lined up in a Hugh McOliver film, but then I’d have to summon the courage to speak to him. Just picturing it makes me sweat: “Excuse me, James? I’m new in class, and (

gasps for air

), and … whew, is it hot in here? I’m just wondering … (

hysterical giggle/gulp

) … um … how can anyone so talented, also be

so gorgeous?

Ahahahahaha excuse me (

Laughs maniacally, runs away in shame

).”

I just need a break—and for that I need a real talent agent. Not one who just sends me out on commercials, but a legit agent who can send me out on auditions for something substantial. I need a speaking part at least, or a steady job at best, something to justify these years of effort that might then somehow, eventually, lead to

An Evening with Frances Banks

at the 92nd Street Y. Most people probably picture receiving an award at the Tonys, or giving their Oscar acceptance speech, but the 92nd Street Y is the place my father loves best, the place he always took me growing up, so it’s easier for me to imagine succeeding there, even though I’ve only ever sat in the audience.

Six months from today

, I think again, and my stomach does a little flip.

Trying to imagine all the steps that come between lying on the chilly floor of my bedroom in Brooklyn and my eventual appearance at the 92nd Street Y, I’m sort of stumped. I don’t know what happens in between today and the night of my career retrospective. But on the bright side, I can picture those two things at least, can imagine the events like bookends, even if the actual books on the shelves between them aren’t yet written.

Finally, my fingertips graze the puffy ridge on the top of my sneaker, and I wedge my shoulder even more tightly under the bed, straining and stretching to grab hold of it. The shoe emerges along with a box of old cassette tapes from high school, my Paddington Bear with a missing yellow Wellington, and a straw hat with artificial flowers sewn onto the brim, which Jane begged me to throw out last summer.

I push these shabby tokens of the past back under the bed, put on my shoe, and get ready to run.

2

You have two messages

.

BEEEP

Hello, this message is for Frances Banks. I’m calling from the office of Dr. Leslie Miles, nutritionist. We’re happy to inform you that your space on the wait list for the wait list to see Dr. Miles has finally been upgraded. You are now on the actual wait list to see the doctor. Congratulations. We’ll call you in one to sixteen months

.

BEEEP

Hello, Franny, it’s Heather from the agency. You’re confirmed for Niagara today, right? Where’s the … Sorry, all these papers! Here it is. Also, just wondering if—do you have a problem with cigarettes? I’m working on a submission for a cigarette campaign to air in France, I think, or someplace Europe-y. Anyway, you wouldn’t have to actually smoke the cigarette, I don’t think—Jenny, does she have to put it in her mouth? No? Okay, so you’d just have to hold the lit cigarette while smoke comes out of it. You’d get extra for hazard pay. Let us know!