Some of My Lives (25 page)

Authors: Rosamond Bernier

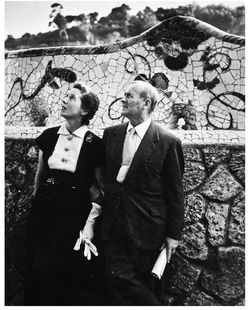

With Miró in the Park Güell, Barcelona, 1954 (© Brassaï)

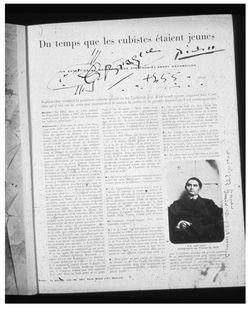

A page from the first copy of

L'ÅIL

, January 15, 1955, signed for me by Braque and Picasso

L'ÅIL

, January 15, 1955, signed for me by Braque and Picasso

The cover of the first

L'ÅIL

, a detail of Léger's

La Grande Parade

L'ÅIL

, a detail of Léger's

La Grande Parade

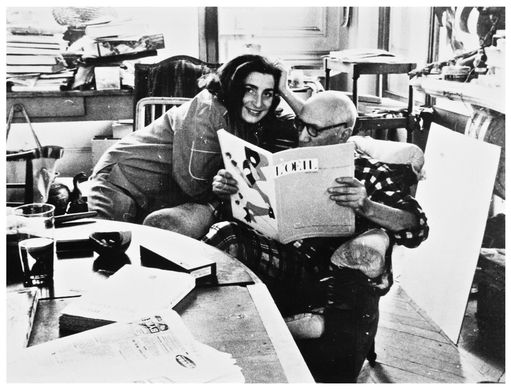

Picasso reading

L'ÅIL

with his wife, Jacqueline, looking over his shoulder (Roland Penrose)

L'ÅIL

with his wife, Jacqueline, looking over his shoulder (Roland Penrose)

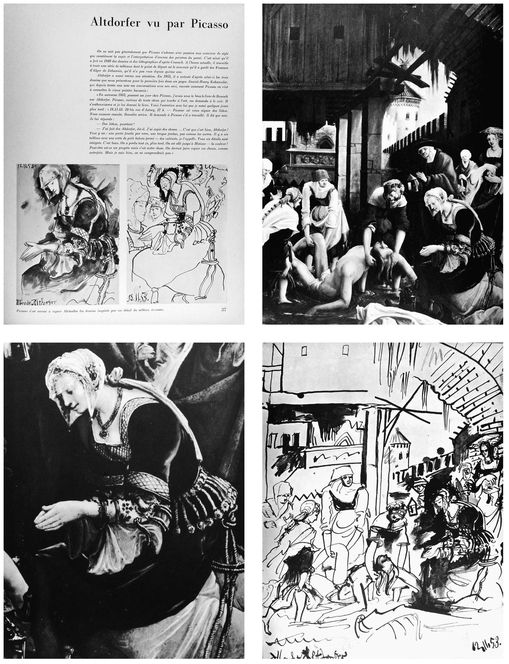

Picasso allowed me to reproduce his copies after Albrecht Altdorfer for the first and last time for

L'ÅIL

in 1957. The drawings disappeared after being returned to him and have never been seen since.

L'ÅIL

in 1957. The drawings disappeared after being returned to him and have never been seen since.

Picasso inscribed this copy of his book

El Entierro del Conde de Orgaz

on the cover and inside for me, 1971

El Entierro del Conde de Orgaz

on the cover and inside for me, 1971

John and me with our hands in plaster (

top

) for a sculpture (

above

) for Louise Bourgeois

top

) for a sculpture (

above

) for Louise Bourgeois

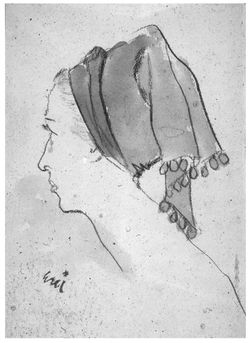

Eric's sketch of me in a Paulette coif, Paris, 1947

Dresses worn over many years for my lectures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Most of these photographs were snapped backstage by John so that I would have a record of what I wore.

Alex Katz's double portrait of John and me, presented to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2010

I

met Max Ernst in the early 1940s in New York. He had managed to get out of German-occupied France and had arrived in the United States thanks to the support of Peggy Guggenheim. She prized him as a catch on several levels: he was a leading figure of the Surrealist movement, and he was outstandingly handsome. He looked like a cross between a noble bird of prey and a fallen archangel. He was known for his beauty of person, his laserlike intelligence, his idiosyncratic command of at least three languages, and his gift for the lapidary phrase that stops the stuffed shirt dead in his tracks.

met Max Ernst in the early 1940s in New York. He had managed to get out of German-occupied France and had arrived in the United States thanks to the support of Peggy Guggenheim. She prized him as a catch on several levels: he was a leading figure of the Surrealist movement, and he was outstandingly handsome. He looked like a cross between a noble bird of prey and a fallen archangel. He was known for his beauty of person, his laserlike intelligence, his idiosyncratic command of at least three languages, and his gift for the lapidary phrase that stops the stuffed shirt dead in his tracks.

Although he had lived in France since 1922, German born, he had never bothered to take out French nationality. As he described it, he arrived in the United States by plane: “Splendid view of the Statue of Liberty. I was met by immigrations authorities, who sent me straight to Ellis Island. Splendid view of the Statue of Liberty.”

The only way out of this impasse was to give in to Peggy Guggenheim's insistence that he marry her, giving him American citizenship. I don't think either of them expected a smooth crossing. As Peggy put it to me, “When Max paints a picture, I like him. When Max sells a picture, I love him.”

We happened to be fellow houseguests for a weekend in the Hamptons. A group of us had been swimming. The beach was a short walk to the house, and there were bicycles. Max and I rode back to the house on bicycles, and so we arrived a few minutes before the others. When Peggy arrived, she made a terrible scene, accusing Max of dalliance with me. Max commented drily, “Not even I can make love on a bicycle.” Later, Peggy told me about this herself and said, “Wasn't I foolish?” which was endearing.

Not much later, Max was sent by Peggy Guggenheim's organization in New York (the gallery she established there was called Art of This Century) to select work by women artists for an exhibition. A singularly unwise move. One of the artists on his rounds was Dorothea Tanning. He went to her studio. She was pretty, a good painter, and she could play chess. They played chess and fell irrevocably in love.

After the inevitable skirmishes and recriminations, the painter Matta lent them some money; they bought a broken-down Ford and headed west, to Sedona, Arizona. I lost touch with them for a while because I went back to Europe. A few photographs arrived, showing a very sunburnt Max, shirtless, and Dorothea (with shirt), literally building their own house.

We met again in the early 1950s in France. The Ernsts had a house in Touraine in a village called Huisme. We had a weekend house not far from them at Suèvres. An evening with them usually turned into a hilarious romp. Max kept a hamper with ridiculous disguises and joke elementsâit was not for nothing that he used to say, “To take the banal and make the marvelous.” Max and Dorothea always outshone us in creating new and often farcical identities. For a fancy-dress ball given by Marie-Laure de Noailles, a famous Parisian hostess, the guests were meant to appear as figures from paintings. Dorothea was a personage from the Netherlandish Master of the Female Half-Lengths: she had half a table cut out and somehow attached to her person, laid out with a complete meal.

The Ernsts moved to Paris. I was living there too. There were many outings togetherâgoing to see the movie

Jules et Jim

, a rerun of a favorite,

King Kong

, sampling restaurants, going to the Natural History Museum to look at rows of exotic beetles.

Jules et Jim

, a rerun of a favorite,

King Kong

, sampling restaurants, going to the Natural History Museum to look at rows of exotic beetles.

I soaked up stories of his peripatetic life. He was born in Germany in 1891 but left it for good in 1922. He left on a passport borrowed from the poet Paul Eluard, who had come to see him with his wife, Gala, who later married DalÃ. Max moved in with the Eluards and became Gala's lover, all this routine according to Surrealist tenets that ruled out conventional rules.

He was an émigré and occasional enemy alien in France and the United States. For his first sixty years and in practical terms, he was over and over again a paperless near pauper, a man on the run who

belonged nowhere. While he may have had uncertain nationality, he never lost his hold on the ultranatural.

belonged nowhere. While he may have had uncertain nationality, he never lost his hold on the ultranatural.

He never lost his faith in chance. He told me that when he was still interned in southern France as an enemy alien, he agonized about how to get his great premonitory painting

Europe After the Rain

safely out of France. (It is now in the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford.) In this painting he had set down once and for all the worst that could happen to a Europe that was overrun, broken-down, and returned to the jungle. How could the painting be kept safe? He decided there was only one way. He would roll it up, wrap it up, and mail it to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He did, and when he got to New York in 1941, there it was waiting for him.

Europe After the Rain

safely out of France. (It is now in the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford.) In this painting he had set down once and for all the worst that could happen to a Europe that was overrun, broken-down, and returned to the jungle. How could the painting be kept safe? He decided there was only one way. He would roll it up, wrap it up, and mail it to the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He did, and when he got to New York in 1941, there it was waiting for him.

It took the world a very long time to recognize Max Ernst as one of the major artists of his century. But when it finally happened, nothing was too good for him. He won first prize at the Venice Biennale of 1954, but not even official honors seemed to follow their ordinary course where Max was concerned.

He had gone to the award ceremony with his old friend Jean Arp, who had won the sculpture prize. The president of Italy, who was to make the presentations, got so carried away by the list of foreign dignitaries attending that he forgot to give the prizewinners' names.

Then Max was stopped in the park grounds, where the Biennale is held, by the carabinieriâthe Italian national policeâwho asked for his pass. He fished ineffectually in his pocket, he had left it behind at his hotel, but he told the guards that he had won the “

primo premio

” (first prize). The men stepped aside and talked, gesturing to each other, clearly indicating that they were saying, “This guy is nuts.” Whereupon they marched him smartly to the exit.

primo premio

” (first prize). The men stepped aside and talked, gesturing to each other, clearly indicating that they were saying, “This guy is nuts.” Whereupon they marched him smartly to the exit.

“That,” said Max, “was my triumph at the Biennale.”

In 1970, I was involved in a divorceâmine. I was living on the rue du Bac, and the Ernsts lived nearby on the rue de Lille. At one point the situation grew unpleasant, and I wanted to move out. Max declared that as long as he was alive, I would never go to a hotel in Paris; in fact, he said, you must come here. The Ernsts had leased an apartment above theirs so that there would be no noise. This became

my temporary headquarters. I arrived to find the Ernsts had improvised a welcome party, and Max had written my name in white icing over a chocolate cake.

my temporary headquarters. I arrived to find the Ernsts had improvised a welcome party, and Max had written my name in white icing over a chocolate cake.

I was actually working at that time on lectures I was to give, in French, at the Grand Palais. One of them was on Max. He had to go to Cologne to collect an honorary bachelor of arts degree, so I had the place to myself. His studies had been interrupted by World War I. As he said, “To get a degree, all you have to do is wait.”

It was curious, and moving, to sit at Max's desk with its miniature red devil on a bicycle (which I now own) and work on my Ernst notes. The lecture went well, but it gave him the wrong idea.

One morning he called me to come down. Usually, I only joined them at drinks time. There was a group of men waiting there, looking expectantly. They were from French television. They had been trying to persuade Ernst to let them do a feature film about him. He always refused. This time, to my dismay and the dismay of the television people, he announced, “This is Rosamond Bernier, she will make your film.” He gave us all a glass of champagne and left.

So French television and I were locked into a shotgun marriage. Max apparently was under the illusion that since I had lectured about him without bothering him, I would do the same thing here. Naturally, I wanted to record him on camera and keep out of the picture myself.

I thought Max might be more relaxed in the sunny atmosphere of Seillans, in the south of France, where Dorothea had designed a large house for them, with a studio at either end.

I had visited the Ernsts there a number of times. Roland Penrose, the English collector and champion of Surrealism, and I had stopped by when the Ernsts were just moving in. Max was eighty, but he was already planting the vegetable garden, some fruit trees, and two kinds of American cornâunknown in these partsâa taste acquired during his stay in Arizona.

So off to Seillans, with a director, a soundman, a lighting man, and a few hangers-on.

It was not easy. My subject was skittish. He might tell me fascinating stories at lunch, but when I asked him to repeat them on camera, he would say, “You know all that. I just told you.” And

there was the inescapable impression that Dorothea thought the film should be about her.

there was the inescapable impression that Dorothea thought the film should be about her.

I doubled as director and occasional guest chef. In the morning, on request, I would make the menu, naming each dish after one of Max's paintings. He liked my cooking, so I would stir up one of his favorites. A photograph records me on the job in the pretty tiled kitchen, a towel around my waist, having just emerged from the pool.

I finally managed to capture Max on film and kept myself out of not only the picture but also the sound track. Unfortunately, French television had a heavy hand in the editing room and added a most inappropriate, grandiloquent sound background.

Some time later, there was a Max Ernst retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, and I was asked to give a lecture about him. I did, with the artist sitting in the front rowâsomewhat disconcerting. When I came off the stage, he had tears streaming down his cheeks. “No one has ever spoken like that about me before,” he said.

The German chancellor, Willy Brandt, was in town and wanted to see the exhibition. Normally, the Guggenheim curator who organized the show would have been asked to show him around. But Max insisted that I do the honors, so I did.

I went with Max and Dorothea to Cologne, where Max's eightieth birthday was celebrated. This prodigal son who had been ignored by his compatriots for half a century naturally enjoyed all the attention. Now the Ernsts were guests of the town in the presidential suite, and he was amused by the flowery tributes, special boat trips down the Rhine, tea with the president of the republic, and the inevitable bottles of eau de cologne. With his usual irony, however, he enjoyed reminding his hosts that his rare exhibitions in Germany, until very recently, had been “total flops.”

He was born in a modest little house in Brühl, near Cologne, which now has a plaque identifying the rare bird that was hatched under these eaves. Just down the road is the great baroque Augustus Palace, once the residence of the prince bishops of Cologne, now used for special state occasions. It has a spectacular staircase by Balthasar Neumann. That is where the state dinner in his honor, hosted by the chancellor of West Germany, was held. It took Max Ernst about eighty years to make the few steps from cottage to castle.

The setting was an exuberant south German rococo fantasy of multicolored marbles, putti sailing through space, angels blowing trumpets, caryatids projecting from a foam bath of stucco ornaments. After numerous courses and speeches, the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, his long blond hair held by a barrette, appeared. He announced, “This is for

lieber

Max,” whereupon a few acolytes twisted some dials and a blast of electronic music thundered out loud enough to project the putti right through the painted dome.

lieber

Max,” whereupon a few acolytes twisted some dials and a blast of electronic music thundered out loud enough to project the putti right through the painted dome.

During one of our many conversations, Max told me that the Impressionists lived in a happy period when people could believe that the retina played the essential role in the creation of art. “One could take one's easel, canvases, and paints and brushes and go off for the day to paint in front of the subjectâthe landscape or whateverâand come back in the evening more or less pleased with what one had done. But this concept of painting was finished by my time. I had decided to become an artist. I had to devise my own answers to the problems.

“I said to myself, when I'm forty, I will stop painting. At the time, that seemed so old to me. I told myself that most painters, once they have achieved a certain result, content themselves with the result. This is not what I wanted to do.

“An artist who finds himself is lost. I had the good luck not to find myself. So I didn't stick to my promise. I went on painting.”

I did not know it at the time, but my future husband, John Russell, was working on a major biography of Max Ernst. When, a few years later, our stories combined, Max wanted to join us formally at Seillans. Only a heart attack thwarted this master of the marvelous from his generous plan.

Other books

La biblioteca de oro by Gayle Lynds

What a Carve Up! by Jonathan Coe

Holdin' On for a Hero by Ciana Stone

Under the Red Flag by Jin, Ha

The Mysterious Disappearance of the Reluctant Book Fairy by Elizabeth George

Red Meat Cures Cancer by Starbuck O'Dwyer

Thai Horse by William Diehl

Hector and the Secrets of Love by Francois Lelord

Castle of Shadows by Ellen Renner

Stage Fright (Nancy Drew/Hardy Boys Book 6) by Carolyn Keene, Franklin W. Dixon