Some Luck

ALSO BY JANE SMILEY

Fiction

Private Life

Ten Days in the Hills

Good Faith

Horse Heaven

The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie Newton

Moo

A Thousand Acres

Ordinary Love and Good Will

The Greenlanders

The Age of Grief

Duplicate Keys

At Paradise Gate

Barn Blind

Nonfiction

The Man Who Invented the Computer

Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel

A Year at the Races

Charles Dickens

Catskill Crafts

For Young Adults

Gee Whiz

Pie in the Sky

True Blue

A Good Horse

The Georges and the Jewels

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2014 by Jane Smiley

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Smiley, Jane.

Some luck : the last hundred years trilogy, a novel / Jane Smiley. — First edition.

pages cm

“This is a Borzoi book”—Title page verso.

ISBN 978-0-307-70031-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-385-35039-6 (eBook) 1. Rural families—Fiction. 2. Farm life—Fiction. 3. Iowa—Fiction. 4. Social change—United States—History—20th century—Fiction. 5. United States—Civilization—20th century—Fiction. 6. Domestic fiction. I. Title. II. Title: Last hundred years trilogy.

PS3569.M39S66 2014

813′.54—dc23

2013041010

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Jacket photograph by Amy Neunsinger / The Image Bank / Getty Images

Jacket design by Kelly Blair

v3.1_r1

This trilogy is dedicated to John Whiston, Bill Silag, Steve Mortensen, and Jack Canning, with many thanks for decades of patience, laughter, insight, information, and assistance

.

Contents

1920

W

ALTER LANGDON HADN

’

T WALKED OUT

to check the fence along the creek for a couple of months—now that the cows were up by the barn for easier milking in the winter, he’d been putting off fence-mending—so he hadn’t seen the pair of owls nesting in the big elm. The tree was half dead; every so often Walter thought of cutting it for firewood, but he would have to get help taking it down, because it must be eighty feet tall or more and four feet in diameter. And it wouldn’t be the best firewood, hardly worth the trouble. Right then, he saw one of the owls fly out of a big cavity maybe ten to twelve feet up, either a big female or a very big male—at any rate, the biggest horned owl Walter had ever seen—and he paused and stood for a minute, still in the afternoon breeze, listening, but there was nothing. He saw why in a moment. The owl floated out for maybe twenty yards, dropped toward the snowy pasture. Then came a high screaming, and the owl rose again, this time with a full-grown rabbit in its talons, writhing, going limp, probably deadened by fear. Walter shook himself.

His gaze followed the owl upward, along the southern horizon, beyond the fence line and the tiny creek, past the road. Other than the big elm and two smaller ones, nothing broke the view—vast snow faded into vast cloud cover. He could just see the weather vane and the tip of the cupola on Harold Gruber’s barn, more than half a

mile to the south. The enormous owl gave the whole scene focus, and woke him up. A rabbit, even a screaming rabbit? That was one less rabbit after his oat plants this spring. The world was full of rabbits, not so full of owls, especially owls like this one, huge and silent. After a minute or two, the owl wheeled around and headed back to the tree. Although it wasn’t yet dusk, the light was not very strong, so Walter couldn’t be sure he saw the feathery horns of another owl peeking out of the cavity in the trunk of the elm, but maybe he did. He would think that he did. He had forgotten why he came out here.

Twenty-five, he was. Twenty-five tomorrow. Some years the snow had melted for his birthday, but not this year, and so it had been a long winter full of cows. For the last two years, he’d had five milkers, but this year he was up to ten. He hadn’t understood how much extra work that would be, even with Ragnar to help, and Ragnar didn’t have any affinity for cows. Ragnar was the reason he had more cows—he needed some source of income to pay Ragnar—but the cows avoided Ragnar, and he had to do all the extra milking himself. And, of course, the price of milk would be down. His father said it would be: it was two years since the war, and the Europeans were back on their feet—or at least back on their feet enough so that the price of milk was down.

Walter walked away from this depressing thought. The funny thing was that when he told his father that he broke even this year, expecting his father to shake his head again and tell him he was crazy to buy the farm when land prices were so high, his father had patted him on the back and congratulated him. Did breaking even include paying interest on the debt? Walter nodded. “Good year, then,” said his father. His father had 320 acres, all paid for, a four-bedroom house, a big barn with hay stacked to the roof, and Walter could have gone on living there, even with Rosanna, even with the baby, especially now, with Howard taken by the influenza and the house so empty, but his father would have walked into his room day and night without knocking, bursting with another thing that Walter had to know or do or remember or finish. His father was strict, and liked things just so—he even oversaw Walter’s mother’s cooking, and always had. Rosanna hadn’t complained about living with his parents—it was all Walter wanting his own place, all Walter looking at the little farmhouse (you could practically see through the walls, they were so thin),

all Walter walking the fields and thinking that bottomland made up for the house, and the fields were rectangular—no difficult plowing or strange, wasted angles. It was all Walter, and so he had no one to blame but himself for this sense of panic that he was trying to walk away from on the day before his birthday. Did he know a single fellow his age with a farm of his own? Not one, at least not around here.

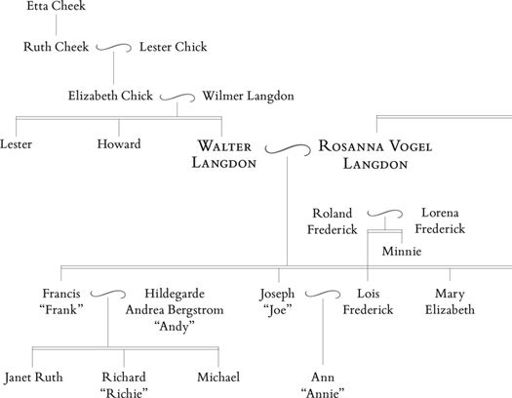

When you looked at Rosanna, you didn’t think she’d been raised on a farm, had farms all through her background, even in Germany. She was blonde, but slender and perfectly graceful, and when she praised the baby’s beauty, she did so without seeming to realize that it reproduced her own. Walter had seen that in some lines of cows—the calves looked stamped out by a cookie cutter, and even the way they turned their heads or kicked their hind feet into the air was the same as last year’s calf and the one before that. Walter’s family was a bastard mix, as his grandfather would say—Langdons, but with some of those long-headed ones from the Borders, with red hair, and then some of those dark-haired Irish from Wexford that were supposed to trace back to the sailors from the Spanish Armada, and some tall balding ones who always needed glasses from around Glasgow. His mother’s side leavened all of these with her Wessex ancestry (“The Chicks and the Cheeks,” she’d always said), but you couldn’t tell that Walter’s relatives were related the way you could with Rosanna’s. Even so, of all Rosanna’s aunts and uncles and cousins, the Augsbergers and the Vogels, Rosanna was the most beautiful, and that was why he had set his heart upon winning her when he came home from the war and finally really noticed her, though she went to the Catholic church. The Langdon and Vogel farms weren’t far apart—no more than a mile—but even in a small town like Denby, no one had much to say to folks who went to other churches and, it must be said, spoke different languages at home.