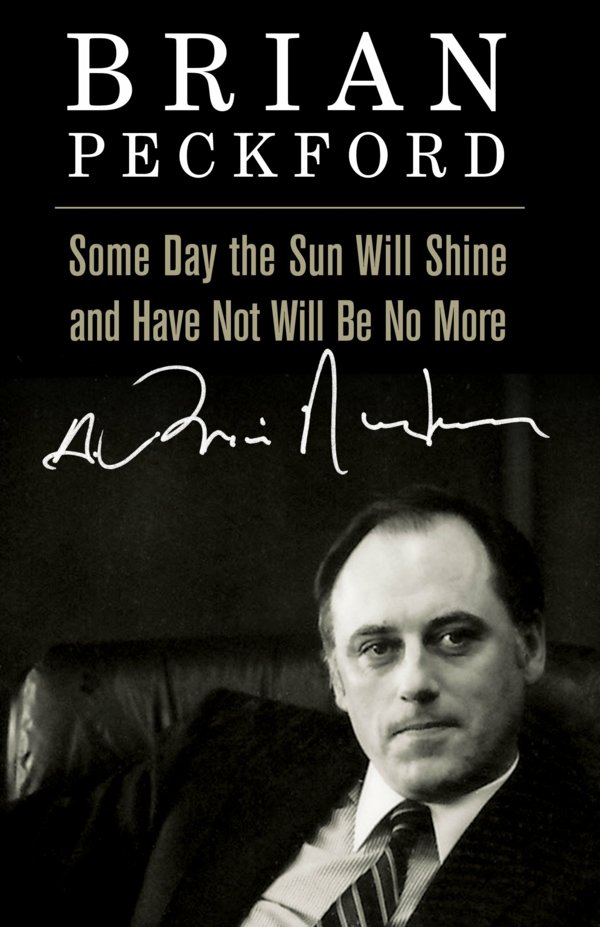

Some Day the Sun Will Shine and Have Not Will Be No More

Read Some Day the Sun Will Shine and Have Not Will Be No More Online

Authors: Brian Peckford

“If we are to achieve results never before accomplished,

we must

employ methods never before attempted.”

â Sir Francis Bacon (1561â1626)

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Peckford, A. Brian

Some day the sun will shine and have not will be no more / Brian

Peckford.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Electronic monograph.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-77117-025-3 (EPUB).--ISBN 978-1-77117-026-0 (Kindle).--

ISBN 978-1-77117-027-7 (PDF)

1. Peckford, A. Brian. 2. Premiers (Canada)--Newfoundland and

Labrador--Biography. 3. Newfoundland and Labrador--Politics and

government--1972-1989. 4. Newfoundland and Labrador--History--1949-. 5.

Federal-provincial relations--Canada. 6. Canada--History--20th century. I.

Title.

FC2176.1.P43A3 2012 971.8’04092 C2012-905010-5

© 2012 by Brian Peckford

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

. No part of the work covered by the

copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic,

electronic or mechanical—without the written permission of the publisher. Any

request for photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and

retrieval systems of any part of this book shall be directed to Access

Copyright, The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 800,

Toronto, ON M5E 1E5. This applies to classroom use as well.

Cover Design: Adam Freake Edited by Erika Steeves

F

LANKER

P

RESS

L

TD

.

PO B

OX

2522,

S

TATION

C S

T

.

J

OHN

’

S

, NL C

ANADA

TELEPHONE: (709) 739-4477 FAx: (709) 739-4420 TOLL-FREE: 1-866-739-4420

WWW. FLANKERPRESS. COM

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the

Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing

activities; the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested

$24.3 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada; the Government of

Newfoundland and Labrador, Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation.

I dedicate this book to all those Newfoundlanders and

Labradorians who remained steadfast against difficult odds so that we were able

to achieve our goal.

The title is taken from a line in a speech I gave, which of course is quoted in

the book. The actual wording was, “One day the sun will shine and have not will

be no more.” Although this book is based on my life, a fifty-year-old memory,

while good, may tend to spice a little for effect.

FOR MANY YEARS NOW I

have been planning to write this book.

The stories, events, and people have been rolling over in my mind on almost a

daily basis.

When I began writing about my experiences as a social worker in rural parts of

the province, I discovered the most unusual thing. It happened one afternoon

when I had begun the exercise. I was writing away in what I thought was a

third-person account of these experiences. I stopped for a moment, and when I

looked at what I had written, I was shocked. I had been writing in the

first-person, complete with dialogue, without my knowing it. And there were

pages and pages of it. I could not believe that I had just written that

material!

I am sure there are those who would say that these short stories are fodder for

another book. For me, they must be in this book since it is only through such

stories that I think one has the opportunity to realize why I was so passionate

about our place. I was lucky to experience both the older way of the early

fifties as a boy and then to see it repeated later in northern Newfoundland and

southern Labrador as a university student before the roads, electricity, and

jukeboxes came to be, and then to experience the transition as it began, and

simultaneously to have been a part of the “new” in Lewisporte and St.

John’s.

These experiences as a student have had a profound effect upon me. I remember

my first political adventure, not counting high school

and

university. I decided to run for the presidency of the Green Bay Liberal

Association at the last minute, and against the person who was being supported

by Premier Smallwood, who was also in attendance at the meeting. In this, my

first political speech (discounting the school and university politics), I

remember using the experiences of my student days to describe my understanding

of the province and hence why I was qualified to run for the office. Of course,

it also signalled that from the start I was anything but an insider. And during

my political career I always seemed most at home when I was in rural parts: yes,

asking for a vote, but being impacted by what I saw and heard, especially the

resilience and tolerance of the people. These experiences seem photographed in

my mind and are an integral part of my sensibility.

It is really not the story of one person, but through one person the lives of

many who thought like me and fervently desired to see a more prosperous place

and our history respected.

The process by which we were able to help to effect this change was anything

but smooth. Of course, there were moments of joy, but most were a struggle and

often it looked impossible.

I am sure there are those who would argue that I overemphasize Newfoundland’s

struggles. Well, my life seems to replicate that view, both my own early

experiences and those in public life. I make no apologies.

Better times have arrived, and let us hope that we have learned from distant

and recent history. I still hold out the hope that, now, through these better

times, we can address our fishery, achieve more influence, and see a revitalized

rural Newfoundland.

“Being grown up is not half as much fun as growing up.”

— Anonymous

BESSIE R

LEFT BAY

Bulls with a cargo of salt for Port aux Basques and

intended to load a cargo of fish at the latter port. It arrived in Fermeuse on

the Southern Shore on Sunday, February 17, 1918, and its master, Sandy Thistle,

fully expected to harbour at Trepassey that night. However, once out and en

route, the fickle forces of nature took command.

Thistle had an experienced crew; most like himself belonged to Hickman’s

Harbour on Random Island: Mate Joseph T. Blundon (or Blundel) and Levi Benson.

Cook John Anderson lived in British Harbour, but he later moved to Britannia on

Random Island. W. J. Peddle hailed from Little Heart’s Ease and Lewis Rice from

Bay Bulls. Joseph Peckford, a well-known citizen of St. John’s, was supercargo

on the schooner. As supercargo he would have managed the business transactions

of the

Bessie R

, whose main work seems to have been trading fish and

supplies along the coast.

The skills of Thistle’s crew were soon to be tried, for the schooner ran

headlong into a snowstorm with southeast winds. Within hours this swung around

to a gale from the northwest—the worst winds for sail-driven vessels off

southeastern Newfoundland. For twenty-four hours

Bessie R

was pushed to

sea, and during the gale the jumbo boom broke off. The log—towed on its line

behind the ship, which would give some indication of speed and distance—broke

and Captain Thistle had no idea how far his schooner had drifted off.

Slowly he and his crew worked the vessel back to within sight of

land, perhaps somewhere on the east side of St. Mary’s Bay. Thistle figured this

was the general area, but

Bessie R

was near a rock called by local folks

The Bull. Thistle didn’t recognize it at the time, but he realized he needed to

keep his schooner out to sea. Despite the best intentions of his crew, contrary

winds pushed

Bessie R

near Holyrood Arm and there was no way to swing the

schooner around to get out. The vessel made its last-ditch standoff the town of

Point LaHayse, or as it is known today, Point La Haye.

Meanwhile, the residents of Point La Haye had gathered on a headland and were

watching the valiant efforts of the six seamen. When

Bessie R

sailed in,

they ran to the beach to help if they could. At first it seemed as if it would

ground and break up offshore. There seemed to be no recourse but disaster and

death. One account of the wreck says, “The people on the shore never thought

that any of the crew would reach the shore alive, and they gathered on the beach

praying for their safety.”

But Captain Thistle drove

Bessie R

right up on the beach and the crew

were able to jump off from the bowsprit to the shore, much to the amazement of

Point La Haye residents. Joseph Peckford sustained the only injury. During the

two or three days of fighting the storm, Peckford had taken his turn at the

wheel and bent over to examine the compass. The main boom swung, hitting him in

the middle of the back, and his chest struck the wheel with considerable force.

One of the wheel spokes injured his chest.

Despite their close call and two or three days of exciting and anxious

hardships, the crew, all but businessman Peckford, went about their life work on

the sea. They found employment at Harbour Grace and went there to join the

schooner

Henry L. Montague

for another stint on the ocean.

This was not the last word on the wreck of

Bessie R

. Apparently one man

was so impressed with the self-rescue of the hardy seamen, he wrote an unsigned

letter to the St. John’s newspaper

Evening Advocate

dated March 11, 1918.

The heading says, “Nothing Can Daunt Our Brave Seamen.”

Dear Sir:

Please allow me space to say a few words about the loss of

Bessie R

at Point La Haye, St. Mary’s Bay, in one of the heaviest seas of thirty

years and in the height of a winter storm. She ran ashore and everything was

handled so well that every man was landed in twenty-five minutes in a way

that no one but Newfoundland fishermen could do.

My pen cannot tell you what a hero Mr. Joseph Peckford is. He nobly stayed

to the wheel until the vessel grounded on the beach and the first place he

was up to was the middle of the storm trysail which was set. If there are

any medals to be given, those men deserve them. There are brave men in all

ranks, but I think seamen beat them all.

Another matter I would like to mention is that I think outport men might

have a little more rum than men in the city. When you drag a man out of the

surf the bottle seems mighty small nowadays. I hope we will be able to get

some more.

Yours very truly,

“A Good Hand to Throw a Line”

Point La Haye, St. Mary’s

In the June 22 edition of the

Trade Review

, as quoted by Patrick

O’Flaherty in his book

The Lost Country: The Rise and Fall of

Newfoundland

, the following article appeared:

One other development in the 1907 fishery should be noted. In June a

fishing craft of “ordinary open boat style” about twenty feet keel

“propelled by a 4 1/2 horse power one cylinder gas engine was in

use in St. John’s. The owner of this “motor boat” was the

fisherman, Joseph Peckford. The engine for those who could afford

one—Peckford’s cost $350—was a major development.

In volume four of

The Book of Newfoundland

, one finds the following

concerning Joseph Peckford:

Peckford fished from the Battery and Bay Bulls for most of his life and

spent 49 years spring sealing. He was a survivor of the Greenland disaster

and was once master watch of the sealing steamer

Florizel

. He is said

to have been the first Newfoundlander to use a gas-powered engine in the

shore fishery. The Knox engine had originally been used in oil exploration

at Parson’s Pond and was purchased by Peckford in 1905. Crowds of people

gathered around the St. John’s waterfront to watch the motorboat on its

trial run. (p. 244)

This was my grandfather Peckford, who came to St. John’s from Fogo Island after

jumping a sealing ship in St. John’s in the 1890s. In St. John’s he met Clara

Brett, also from Fogo Island, and married. Joe fished out of St. John’s harbour

for fifty years and reportedly went to the seal fishery for forty-nine years,

and my grandmother kept a small store. The Peckford home that Joe built still

stands; some of his wharf and rooms were at the bottom of Temperance Street, now

all filled in as part of harbour enlargement and on which the Terry Fox Memorial

now stands.

In 2009 I visited Fogo Island to further investigate the birthplaces of these

two grandparents: Locke’s Cove and Lion’s Den. Walking a wonderful new walking

trail on a glorious August day, I visited Lion’s Den and Locke’s Cove. It was

only then that I realized that Joe and Clara had likely known one another before

their St. John’s days, as the distance between both places was not great. Who

knows? They might have been earlier lovers and Joe’s jumping ship was to find

his lost love. Curiously, no headstone remains of the Peckfords

on Fogo Island. After some crawling around in one of three cemeteries, I found a

fallen headstone of my great-grandfather Jonathan Brett, Clara’s father, who it

is reported was a shipbuilder.

My maternal grandparents were Hiram Young and Queen Victoria Ross.

Great-grandfather Young moved from Greenspond, his birthplace, when my

grandfather was a young boy. Queen Victoria was born on the Ross farm, now

Pleasantville. The Rosses were originally from Margaree Valley, Cape Breton

Island. My grandmother, who kept a diary, recorded the following:

I was born on March 23, 1885, in St. John’s, Newfoundland. As far as I know

I was born in an old farm house called Grove Farm, Quidi Vidi Road, North

Side. At that time I had seven sisters, six of whom were born in Margaree,

Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. The Ross name is a well-known name in the

Margaree area seeing five different families of Rosses immigrating there

from Scotland in the 1700s, each claiming they were unrelated to the

other.

Great-grandfather Ross owned 100 acres of what is now Pleasantville, formerly

Fort Pepperell, and farmed there, supplying St. John’s with vegetables, milk,

and cream, including the General Hospital and the Governor’s House. He operated

a store on Water Street at one time, imported cattle from the Maritimes, and

raised thoroughbred horses. Grandmother Ross actually taught weavery at Mount

Cashel orphanage at one time. An enterprising lot!

Of course this enterprise came naturally, if one studies this Ross family. My

great-great-great-grandfather David Ross was brother to James Ross, the first of

his clan to settle in Margaree and third husband to Henriette LaJeune. She

fought with the French (coming from France herself) at Louisbourg when it fell

to the English. She had a medical background and became famous in Cape Breton

for nursing, administering the smallpox vaccine that she had brought

from France. She became affectionately known to all as Granny

Ross and lived to the age of 117. At St. Patrick’s Church in northeast Margaree,

there is a cedar sign which reads:

Welcome to St. Patrick’s Church

Built in 1871 on land granted

To James Ross, English Pioneer

For fighting at Louisbourgh in 1758.

Buried in this graveyard is his wife

‘The Little Woman’

Who fought for the French.

A memorial (although there is now some dispute over the veracity of her age) on

the south side of the church reads:

In Memory of

The Little Woman

Henriette LeJeune

Wife of

James L. Ross, pioneer

The first white woman to settle

In North East Margaree

Born in France 1743

Died in Margaree in 1860

Fought with the French in the

Second Siege of Louisbourgh 1758

Administered smallpox vaccine

Brought with her from France

To the settlers of this valley

Benefactress of both white

And Indian.

Erected by her Great Grandson

Thomas E. Ross

I WAS BORN IN

Whitbourne, a small railway town just sixty

miles from St. John’s, one of a handful of communities in Newfoundland that was

not next to the ocean. Although both my parents were St. John’s people, my

father’s position with the Newfoundland Ranger Force necessitated that he be

stationed at the force’s training facility in Whitbourne. I remember the train

passing through the town and how we kids would play close to the moving train,

almost daring it to touch us. I remember taking it to St. John’s with my mother,

and riding the streetcar in bustling St. John’s. Years later as a university

student I would take the train home for Christmas to Lewisporte, and even later

I was to take the train in an unsuccessful attempt to save it.

My first three years of school were in Whitbourne, the Anglican School; the

Catholic one was just across the road, just close enough so that we could throw

snowballs at one another in winter. You did not have to attend church to know

that there were major separations in the community. You knew through school. And

it was weird since it was the same God, same Jesus, and same book. But little

was said other than you were United, Salvation Army, or Anglican, or that real

strange one, Catholic. And that is the way it was. But fate was soon to bring me

closer to that strange denomination, only we called them religions then.

In December, 1951, when I was the age of nine, the family moved to Marystown,

my father having changed from being a law enforcement officer and small business

owner to a social worker. After his social worker training he was posted to

Marystown, a small, undeveloped community over 200 miles from St. John’s on the

Burin Peninsula. It was more isolated than Whitbourne and without electricity;

farther along the peninsula were the more developed towns of Burin, Grand Bank,

and Fortune, all economically active with fish plants serviced by offshore

trawlers.

It’s a bit of family lore as to how the family arrived in Marystown. Father had

gone to Marystown a few weeks earlier in December to finalize arrangements for a

house and to meet with the outgoing social worker and other such matters. Mother

and her brood of five were to follow later. There was a ninety-nine-mile drive

from the Goobies

railway station to Marystown, and we were to

travel there by train from St. John’s, a further 100 miles. Father would pick us

up there in a rented vehicle and drive all the family to our new community, to

our new home. Ah! The best-laid plans . . .

To Goobies we arrived—in a snowstorm—and Father was somewhere on the

ninety-nine-mile gravel highway, stuck in snow. So here we were—no doubt a

forlorn-looking group. Someone at the railway station who knew of a boarding

house nearby took pity on us and we were brought there to reside overnight. The

next day we learned that it would be impossible for Father to meet us—the road

was blocked. In those days, without the mechanical machinery of today, it would

be blocked for quite some time. Father would go back to Marystown. A new plan

had to be devised. Back to St. John’s we were to go, and to take a train as soon

as we could (a half-day journey) to the port of Argentia, where we could catch a

coastal passenger freight boat, which plied Placentia Bay communities including

Marystown.