Solomon's Secret Arts (3 page)

Read Solomon's Secret Arts Online

Authors: Paul Kléber Monod

13

The beaming countenance of Ebenezer Sibly, from his

Medical Mirror

(1794), displays the confidence of a Member of the Royal College of Physicians, Aberdeen. The initials “F. R. H. S.” probably refer to a branch of the Harmonic Society, which was dedicated to magnetic healing; the “R” may stand for Rosicrucian rather than Royal. No doubt Sibly was a founding Fellow. The only other occult reference here is to Mercury, who bears alchemical symbols on his shield. The vignette at the bottom of the page depicts the Biblical story of the Good Samaritan, and at right is the Nehushtan, the serpent wound around a staff that appeared to Moses—obviously, a Scriptural counterpart to Mercury's staff or caduceus.

14

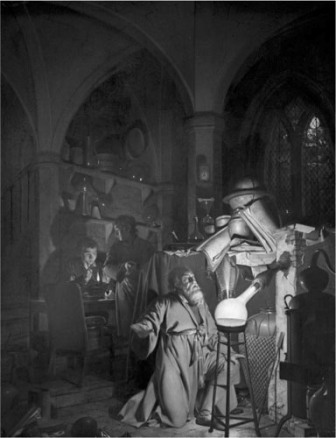

The immediate source of light in Joseph Wright of Derby's remarkable painting, “The Alchymist,” may be the glowing retort containing phosphorus that radiates at the centre of the alchemist's laboratory, but the vessel merely reflects the divine light dimly viewed through the window at the top of the scene. The picture is heavily laden with references to Freemasonry that would have been obvious to any initiate.

15

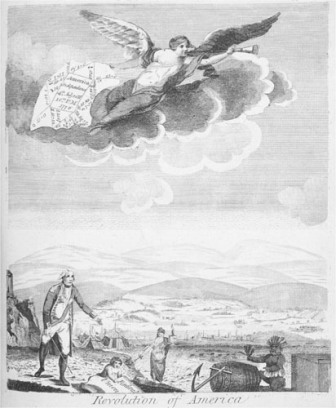

Ebenezer Sibly's famous astrological chart of the birth of the United States on July 4, 1776, is carried aloft by a winged figure of Victory. Below, George Washington gestures towards Justice and a young Federal Union, while a rather ludicrous looking Indian, derived from tobacco advertisements, toasts him and points to symbols of trade. A military camp and a prosperous port town are seen in the background. This is a rare example of a strongly pro-American print, engraved in England only 12 years after American Independence.

16

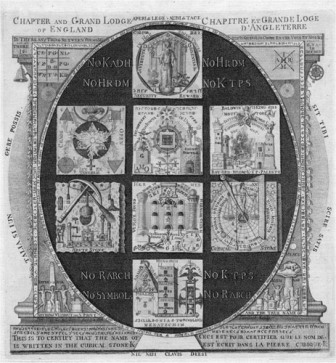

The most imaginative and detailed of Peter Lambert de Lintot's Masonic engravings, dating from 1789, displays the symbols of the different degrees granted by the breakaway Grand Lodge of England. The use of alchemical imagery and language (“Chaos,” “Hermes,” etc.) is striking, as are the multiple representations of Solomon's Temple. The arrangement of the seven degrees might be compared to Newton's plan of the Temple. The inscriptions around the edges are written in English, French and an indecipherable quasi-Hebraic script (perhaps the language of Adam) for the benefit of the multi-cultural members of the Grand Lodge.

17

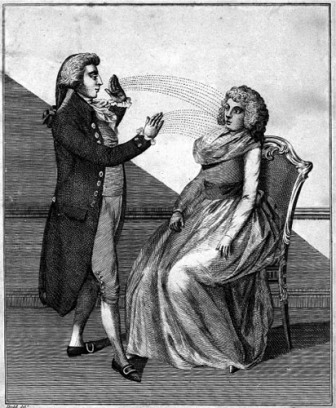

The famous depiction of animal magnetism from Ebenezer Sibly's

Key to Physic, and the Occult Sciences

(1795) shows a male magnetizer operating on a female patient. He stands at a discrete distance from her, his hands radiating magnetic energy at her face and breast. She sits passively and registers no visible signs of a “Crisis”. This was a tame representation of the controversial therapy, engraved at a point when it was no longer widely acceptable among the English elite.

18

The morose and misguided Urizen calmly measuring out the universe with a compass at the opening of William Blake's

Europe: A Prophecy

. The instrument is an unmistakable reference to Freemasonry, and to the Masonic concept of God as the architect of the universe. Urizen's uncomfortable crouch also resembles the bending pose of Isaac Newton in a print issued by Blake in 1795, where the great scientist uses a compass to measure out a conical section. The compositional structure of the Urizen painting, with its combination of a circle and a triangle, can be compared to the alchemical diagram in

The Philosophical Epitaph of W.C. Esq.

, which was in turn derived from the illustrations to Jacob Boehme's works. In the end, however, Blake's personal vision trumps Masonry, Newton, alchemy and even Boehme.

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

T

HIS BOOK

has taken longer to realize than any alchemical recipe known to me. The journey, however, has been fascinating. It has included a visiting fellowship at Harris Manchester College, Oxford University, in 2001–2, as well as research fellowships at the Getty Research Institute in 2004 and the Huntington Library in 2008. During a leave year in 2007–8, research on this project was supported by a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The most consistent support came from Middlebury College, largely through the A. Barton Hepburn Professorship. Parts of this book have been presented in seminar talks at the University of California at Los Angeles, the Newbury Library, Warwick University, the University of Glasgow and McGill University, as well as conference talks at the Università del Salento in Lecce, the British Institute, the University of Strathclyde, the Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen and the Karl Franzens Universität Graz. The organizers of those seminars and conferences deserve gratitude for inviting me to speak on often half-baked ideas.

I must also thank a host of individuals who assisted me along the way with advice, information, suggestions and comments. They include David Armando, Robin Briggs, Bob Bucholz, Louisa Burnham, R.J. Evans, Antoine Faivre, Joscelyn Godwin, Anthony Grafton, Wouter Hanegraaff, Ronald Hutton, Sarah Hutton, Colin Kidd, Jim Larrabee, Diarmaid MacCulloch, Scott Mandelbrote, Alex Marr, Mark Morrisson, Victor Nuovo, Kapil Raj, Peter Reill, Isabel Rivers, Teofilo Ruiz, Bill Sherman, Marsha Keith Schuchard, Susan Sommers, Bob Tittler, John Walsh, David Womersley and David Wykes. The staff at all the institutions listed in the bibliography deserve praise, in particular those at the Getty Research Library, the Clark Library, Dr Williams's Library, the Library of Freemasonry, Swedenborg House and Chetham's Library. I must especially thank the duke of Northumberland for permission to use the archive at

Alnwick Castle, and the estate office at Alnwick for assisting me in working there.

My greatest debt, as always, is to my wife, Jan Albers, who has lived cheerfully with this rather offbeat project for the past eleven years. Our son, Evan, wonders why I am not able to perform conjuring tricks, because he does not realize that he is the best magic his mother and I could produce. My own mother has provided constant reminders of how receptive West Country Methodists were to the supernatural, while my late father bequeathed to me a French-Swiss scepticism that occasionally surfaces in this book. In carrying out research, I have depended on the unflagging hospitality of Colin and Lucy Kidd at Glasgow, my ever-welcoming cousin Margaret Monod and her wonderful partner, Joyce Chester, in Sussex and my dear uncle Dennis Donovan, who kept me up to date with happenings in his village of West Lydford, Somerset, where John Cannon lived.

This book is not a gateway to occult knowledge, but it should help to explain why that knowledge has been of such vital interest to past generations of Britons. What distinguishes the British version of the occult is its openness to both learned and popular ideas, making its history intellectually messy yet constantly surprising. If this book brings some surprises, a few insights and some pleasure, then perhaps its flaws, which are entirely my own responsibility, may be forgiven. As for the Philosopher's Stone, readers, seek that out for yourselves.

Weybridge, Vermont, June 2012

I

NTRODUCTION

What Was the Occult?

L

IKE POVERTY

, death and taxes, the occult seems always to have been with us. From the mysterious cave painters of Lascaux to today's online astrologers and televised psychic readers, human beings throughout history have sought ways of tapping into hidden powers, to gain knowledge and influence through what is now commonly referred to as “the unexplained.” Contemporary British culture is hardly immune to a fascination with the occult—witness the immense popular success of the Harry Potter novels, replete with witches, wizards and alchemists, or the stupendous magical confrontations of the

Lord of the Rings

film trilogy, or any number of “sword and sorcery” computer games. More serious manifestations of occult belief, from Spiritualism to Wicca to Druids to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, have proliferated in Britain over the past century. Although the United States (where the Golden Dawn has been incorporated since 1988) is now the intellectual hub and chief recruiting ground for occult organizations, a large number of them have British origins or maintain affiliates in the United Kingdom. “Occultism” is often associated with the New Age religious philosophies of California, but many of its roots are thoroughly British.

1