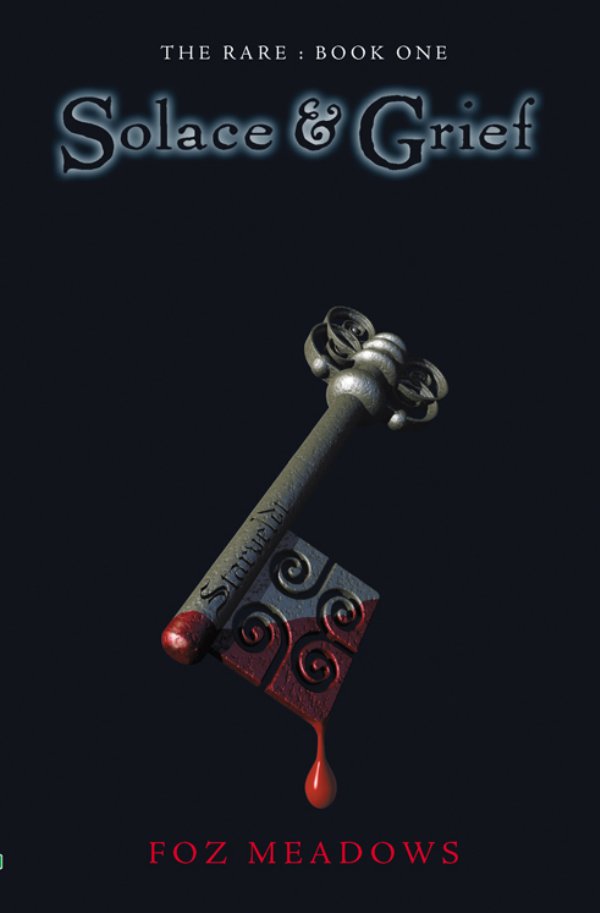

Solace & Grief

Authors: Foz Meadows

Foz Meadows

First published by Ford Street Publishing, an imprint of

Hybrid Publishers, PO Box 52, Ormond VIC 3204

Melbourne Victoria Australia

© Foz Meadows 2010

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to Ford Street Publishing Pty Ltd

2 Ford Street, Clifton Hill VIC 3068.

Ford Street website:

www.fordstreetpublishing.com

First published 2010

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Author: Meadows, Foz

Title: Solace and grief / Foz Meadows

ISBN: 9781876462895 (pbk.)

Target audience: Young adults

Subjects: Vampires – Young adult fiction.

Dewey Number: A823.4

Cover design: Gittus Graphics ©

In-house editor: Saralinda Turner

Printing and quality control in China by

Tingleman Pty Ltd

For Kathryn, who came first,

Angus, who knows why,

and most of all for Toby,

best of bears.

4. Infrequently Asked Questions

9. Dungeons, Castles & Other Anachronisms

17. Where Angels Fear To Tread

B

ehind its curtains, the room was dark and quiet. In one corner stood an antique four-poster bed, sheltered on all sides by tattered hangings of white gauze, ghostly against the black wood. Half-obscured from view, a woman lay sweated to the sheets, her limbs tangled and pale. Though weak, she was also beautiful: soft, black hair framed a delicate, fine-boned face, while her eyes were as fathomless as spilt ink. This trait she shared with the man kneeling by her side, although in all other respects he seemed the dawn to her dusk, light where she was shadow. Silently, the pair held hands and looked tenderly down at the room's third occupant: their newborn daughter, nestled in the crook of the woman's arm. The baby's eyes, too, were liquid black, fixed on her father with an eerie mixture of infant solemnity and adult focus. She blinked rarely, and otherwise lay unnaturally still, her tiny chest scarcely rising or falling. Sweat pearled her too-pale skin. Had any observer feared she was dying, they would have been right.

In a manner of speaking.

Moving with the languor of exhaustion, the woman raised her free hand and bit down hard on the wrist, wincing with pain and effort. There was a slurping sound, a flash of teeth. Carefully, spilling nothing, she reached across and let the redness drip into her daughter's barely-open mouth, sighing with relief as the baby swallowed. When the woman finally pulled away, the man took over, biting his wrist to feed the child, such succour, whatever else, being gender-neutral.

In time he too stopped. Neither parent had lost much blood, and yet the giving of it had drained them, as though something even more vital had been exchanged; and perhaps it had. A deathly pallor clung to them. Swaying, the man grasped heavily at the bed, slipping enough that the ragged curtains danced and shivered. Beside him, the woman laboured for breath.

‘Call her,’ she managed. The man nodded. His free hand quested blindly across the ground, eventually coming to rest on a small, bronze bell with an ivory handle. As though his touch had wakened it, a stray beam of light chose that moment to glance off the warm metal, drawing the eye with a strange, fey glow. Hesitant, the man let his fingertips linger on the ivory until, with effort, he lifted the bell and rang it. The sound rippled sweetly through the air, twisting like unfallen motes in a ray of light. With an answering shudder, his hand wrenched open: the bell dropped askew, but somehow landed upright on the wooden floor – steady, as if it had been carefully set down.

From outside the room came the snap and creak of uncertain floorboards as someone shifted their weight from seated to standing. With a rough murmur, the door opened to reveal a thirty-something woman, dressed as a nurse. She halted at the threshold. Her eyes were a watery blue, as vague and unfocused as the baby's should have been, and when the man beckoned, she entered.

‘Take the child,’ he instructed, now gasping for breath. ‘You understand? We have told you what to do and where to go. Take the child.’

‘Take the child,’ repeated the nurse. Her voice seemed to come from far away, as though her tongue were remembering automatically what her brain had forgotten.

‘Her name is Solace,’ the woman said.

The nurse blinked.

‘Solace,’ she echoed. ‘Her name is Solace.’

The woman smiled with weak relief. The man rubbed his face, perhaps in frustration, perhaps to forestall tears. The fingers of his left hand twitched – dismissal.

‘Go, then. Take her. Go.’

The nurse nodded jerkily, but her other movements were sure, their precision ingrained deep in muscular memory. It was she who'd delivered the baby, cleaned the child and burned the bloodied sheets, even replacing them with fresh linen, but the man's control had made her forget. Seeing without seeing, she looked at her charge. The infant was half-swaddled in a white blanket, arms resting free. A cap of black down covered the crown of her head, and there was a red smear on her lips, although the nurse, in her altered state, saw nothing odd in this. As she was lifted away, the girl raised a tiny hand, seemingly without thought, towards her exhausted parents. Both mother and father brushed their fingers against hers, and for an instant their strange, small family seemed frozen in time, each connected to the other by a skin of atoms. Then the moment passed; the nurse moved on, and the two tired occupants – one light, one dark – fell back. Content in the arms of her carer, the baby gurgled and closed her eyes. Her breathing had improved.

‘Go,’ the man repeated.

The nurse went, and the door swung shut behind her.

‘She will be safe?’ The woman's query echoed in the musty room. It already smelled of death. The man nodded. Unable to stay upright any longer, he rested his head on the mattress, blond hair dark with sweat, and barked a dry laugh.

‘Safe enough,’ he managed. ‘As safe as anyone ever is.’

‘I only wish –’

‘I know, love. I know.’

Weeks later, for no reason she could explain, the nurse went back to the old building. She hadn't expected anything, but found she was inexplicably untroubled by her discovery of the two corpses. Had she recalled ever seeing them before, she might have noted that neither the man nor the woman had moved since her departure, nor had they decayed in death. A fine layer of dust covered the bronze and ivory bell. She was tempted to take it, but left the scene undisturbed.

‘Good,’ she said.

And then, her mind blank, she left the building, returned to her car and drove away, never to call the police or disclose what had happened. Often in the following days she was troubled by an uneasy, nagging guilt, as though she'd forgotten something important, but in time, even that ceased.

The man had made certain of that. She'd been meant to forget everything.

Almost.

Y

ou shouldn't be here

.

The words resonated bluntly, jarring her into consciousness. Solace Morgan blinked, struggling through the combined disorientation of broken sleep and faded dreams for some context with which to interpret the thought, but none was forthcoming. Instead, the phrase hung naked in her head, a disquieting slogan.

‘I shouldn't be here?’ she asked aloud, tasting morning muzziness on her tongue. ‘Yeah. That sounds about right.’

Sitting up, she swung her legs over the mattress edge, shivering as her bare soles scraped the floor. Autumn, it seemed, had packed its bags, and winter was at the door.

The analogue wall clock read 8:17, but Solace knew it lied: because Luci, for reasons known only to herself, had set it thirty-eight minutes fast. Miss Daisy and Mrs Plumber tried their best, of course, but in defiance of all persuasion, the tiny girl refused to mend her ways, regularly resetting every clock in the house to its own unique calibration. This week, she'd been merciful: no dissonance was greater than an hour, although there were, in perverse balance, a larger number of awkward minutes. Sighing, Solace made the mental adjustment to 7:39 and headed for the bathroom, hoping Leonie wasn't already barricaded in. Again.

As things turned out, Solace had a rare clean run, showering and dressing without so much as a peep from her housemates. It wasn't until she made it downstairs for breakfast that she realised why: it was Saturday, and the others were still asleep. Groaning only a little, she opened the fridge and scanned for viable foodstuffs. Much to her regret, Solace's diet was forcibly limited to meat, sweets, bread and a handful of fruit and vegetables, as most anything else made her throw up violently. Numerous doctors had scratched their heads at this.

Technically

(they always said),

technically,

she wasn't allergic. No rash, no constricted breathing, no hives, nor even any real poisoning. Her body just rejected what was put into it. Though undeniably frustrating, it was something she'd learned to live with. On the plus side, at least she remained exempt from Miss Daisy's occasional vegetarian crusades, while bacon sandwiches held not a shred of guilt.

Finally spying a plate of cold sausages, Solace helped herself and pulled up a chair at the edge of the table, chewing idly as she considered her faint reflection in the glass door opposite. Even unwashed, her fine, thick hair clung silkily to her neck and face, with odd strands drifting loose like black cat whiskers. Her eyes were black, too, or else so dark a brown as to moot the difference. Her skin was Northern fair: not china-white, because china

gleamed,

but linen-pale, as soft and semi-translucent as her favourite old sheets. Fashion-wise, Solace often thought she'd make a good Goth, but with Miss Daisy and Mrs Plumber firmly in charge of her wardrobe, the opportunity of finding out had never presented itself.

From outside, she heard a familiar clicking sound: the side gate being unlatched. Thoughtfully, she gulped the last of her sausage, thumped a foot against the chair leg and sing-songed a ‘five, four, three, two,

one

’ countdown on each exhaled breath. Then: ‘Liftoff!’ – just as the door creaked open. A spindly pair of high heels clinked on the threshold.

Annamaria, unlike Solace, chose her own clothes; indeed, she often neglected to pay for them. Apart from the heels, she was wearing a tight faux-leather miniskirt, a gold halter-top overburdened with diamantes, large hoop earrings, entirely too much make-up, and a wary, hung-over expression.

‘They up?’ she asked, over-casual. Her eyes darted from the oven clock (8:19) to the microwave LCD (7:07) before finally lighting on Solace, who shrugged.

‘Not yet. How's Blake?’

‘Peachy, not that it's any of yours.’ Annamaria flashed her gentlest scowl. ‘Bathroom free?’

‘Should be.’

The blonde girl gave a grunt of acknowledgement, bending to slip her shoes off. The backs of her legs were bruised, Solace noted, but not, thankfully, from needles. Probably she'd just banged herself or slipped in her ludicrous stilettos. The glitzy straps sparkled as Annamaria dangled them from a finger.

‘I won't say a word,’ said Solace, answering the unasked question. Tilting her chin, Annamaria toyed with a strand of dry, peroxided hair. The roots were starting to grow out.

‘Thanks.’ She paused, opened her mouth again, but didn't speak. Then, setting her jaw, she padded silently from the kitchen and down the hall, her creeping footsteps on the distant stairs echoing in Solace's sensitive ears.

Solace stopped listening once the shower turned on. Annamaria was fifteen and had been at the group home just a few months, stranded after her last foster-mother had died unexpectedly of a heart attack. Luci, by contrast, had arrived five years ago at age three: she'd been fostered out since, but problematic behaviour, like getting into fights or flooding houses, always brought her back. Leonie was eleven, and didn't speak - or at least, not in any fashion Mrs Plumber and Miss Daisy understood. She'd come to them a year ago, mute from a horror that neither adult would openly discuss, but which Solace had nonetheless managed to overhear, and afterwards wished she hadn't. They were damaged, or dangerous, or some combination thereof, at least as far as the system was concerned, which was why they'd been placed in the care of Sarah Plumber (widow) and Daisy Elkton-Sprague (relationship pending). Only Annamaria attended school, and even then, it was more in theory than practice. The others were tutored internally in a kind of home/ Steiner school, depending on how cooperative Leonie and Luci were feeling.

Solace, however, was a different story, having arrived at the group home in infancy and without ever managing to leave. It was, she reflected, a decidedly unusual situation. Her very first carer, one Clara Morgan, had planned to adopt her, only to inexplicably change her mind – and, indeed, move countries – at the last minute. Solace had taken a surname from the incident, but little else: she'd returned to the group home, where a dearth of prospective parents (and a string of besotted house-mothers) had seen her stay. At age three, a childless couple mysteriously failed to appear on the eve of signing adoption papers, a sad peculiarity which occurred no less than eight times throughout her childhood. For a while, the young Solace had suffered nightmares about being cursed, fearful that something about her was innately wrong or repulsive. It took the arrival of Mrs Plumber and Miss Daisy shortly after her ninth birthday to master that fear, as the pair went on to become the closest thing she'd ever known to parents.

She didn't attend school, either, but existed in a constant state of administrative flux, learning from whoever was available and socialising exclusively with the likes of Luci, Leonie and Annamaria, children whose own bad circumstances or behavioural quirks had seen them forced from the mainstream. By age twelve, she'd started to chafe fiercely at her situation, simmering in quiet indignation at the strange, nonsensical barriers separating her from the real world. She'd turned sullen and resentful, snapping at Miss Daisy's questions and playing truant from Mrs Plumber's lessons, although thanks to some internal, guilty compulsion, she never strayed farther from the group home than a block or two. And then, one insufferably awful day, Kelly – an older girl, delinquent, cruel – had mocked her for a freak; and Solace had snapped, picking up the kitchen table and hurling it through the glass doors, screaming in rage and frustration. The table, which weighed a good forty kilos, had clipped Kelly's shoulder as it flew by. She went to hospital with a fractured collarbone and returned a meeker individual, albeit temporarily, while Solace received neither the reprimand nor the anger management sessions she'd been dreading. Instead, she was treated to several weeks of awed quiet, not only by her housemates (including Luci, then a toddling newcomer) but by the adults, too. It was an awful time, and her childhood nightmares resurfaced, warped with pubescent angst.

There'd been other changes, too, not all of them hormonal. Solace's skin began reacting badly to sunlight, turning perversely pale the longer she was exposed, as though she were bleaching into translucency. The inhuman strength with which she'd hurled the table didn't abate, but continued to come in waves, rippling through her slender frame like a series of electrical surges. Each one left her stronger than the last, until, by the time they stopped at age fourteen, she was able to bend metal. Her senses, which had always been acute, intensified and where before she'd been able to drink milk, her body now rejected it. Some of these changes she kept secret; others were harder to hide. After the incident with Kelly, word seemed to carry to each new housemate that Solace was not to be trifled with, and so they stayed away, or treated her warily, even the wild ones. Mrs Plumber and Miss Daisy noticed but they too seemed unwilling to pry into her affairs. Trapped by silence, she resolved to break it, asking questions of everyone and anyone out of a half-formed desire to provoke conflict. But here was another queer ability: her questions earned answers they didn't deserve, prising out secrets like black oil from earth. The power of it frightened her: on some marrow-deep level, she

knew

the honesty was her fault. She became quieter, more cautious, and asked nothing she didn't genuinely want to know.

Not long before Solace turned fifteen, she watched

Dracula

on TV, a black-and-white version with overly dramatic music and fainting damsels. As the Dark Prince leered over Miss Mina's neck, she found herself idly wondering what it would be like to bite someone. Her own teeth were noticeably sharp (

all the better to eat you with, my dear),

but not malformed, and as she ran her tongue over them, probing, a bizarre, speculative thought occurred: that perhaps

she,

Solace Morgan, had been a vampire all along. Certainly, she didn't like sunlight; her diet consisted mainly of red meat; she was strong in a way unheard of outside bodybuilding competitions or sci-fi flicks; and then there was the question of thrall, which was as good a word for her persuasive skills as ever she'd encountered. Why should bats and silver have anything to do with it? At that, she began to tremble, hugging herself, and though she dismissed the notion as late-night jitters, something of it lingered.

Sighing, she stood up from the table and carried her empty plate to the sink. Tomorrow, she'd be seventeen: only one year from freedom. It was an intoxicating thought, but also a frightening one. As she soaped the cold grease from her fingers, she contemplated, not for the first time, what it would be like to make her own decisions, live in her own apartment, have her own friends. What kind of work might she do? Insofar as she was able to judge, her marks had always been good, despite Mrs Plumber's tendency to deploy her in class as a buffer between the most disruptive element and everyone else, but would they count in the real world? Social problems were equally concerning: there'd rarely been boys in the group home, and all of them young. Thomas had been the last, she recalled, a shy pyromaniac who'd left some weeks before Luci's arrival. Since then, Solace's sole interaction with the opposite sex had come from TV and trips to Westfield. Which of these was least helpful was anyone's guess.

‘I'll do fine,’ she muttered. ‘I'll manage.’

‘Manage what?’

Solace jumped. It was rare that someone snuck up on her, but lost in thought, she hadn't heard Luci approach. Turning, she smiled as the little girl hugged the edge of the doorway, the ends of two ratty, slept-in plaits brushing against her Minnie Mouse nightie.

‘Nothing. How're you?’

Luci stretched theatrically. ‘Hungry! Can I have some breakfast?’

‘Depends on what you want. We're out of cereal.’

‘Crap,’ said Luci.

Solace raised an eyebrow. ‘Mrs Plumber doesn't like you swearing.’

‘Mrs Plumber can bite me.’

‘Luci!’

The eight-year-old giggled and poked out her tongue. ‘Toast, then? Please?’

Rolling her eyes, Solace opened her mouth to tell Luci to heat her own bread when she remembered the Exploding Jam Incident and thought better of it.

‘How many slices?’

‘Two.’

‘Okay. Just sit down and wait.’

She worked in silence. Luci was many things, but a chatterbox wasn't one of them, and so she sat obediently at the table, content with thrumming her fingers on the wooden top. ‘Strawberry jam,’ was her only comment on hearing the toaster pop.

Solace was just serving up when Miss Daisy arrived downstairs, yawning in pleasant surprise at their seeming domesticity. Nodding a hello to Solace, she reached for the topmost cupboard where the coffee was kept and spoke without turning around, her voice carefully neutral.

‘Luci, you wouldn't happen to know who's been playing with my clothes, would you?’

‘No, Miss Daisy,’ Luci said through a mouthful of toast. Solace poured herself a glass of water, watching her house-mother's expression through sideways eyes. Miss Daisy frowned.

‘You're very sure? Someone's cut some words into my favourite shirt. It's not a very nice thought, Luci. Could it have been part of a game?’