Socrates (4 page)

Authors: C. C. W. Taylor Christopher;taylor

There is also some evidence that Socrates’ personal religious behaviour and attitudes were seen as eccentric. He famously claimed to be guided by a private divine sign, an inner voice which warned him against doing things which would have been harmful to him, such as engaging in politics (

Apol

. 31c–d), and in the

Apology

(ibid.) he says that Meletus caricatured this in his indictment. Of course, there was nothing illegal or impious in such a claim in itself, but taken together with other evidence of nonconformity it could be cited to show that Socrates bypassed normal channels in his communication with the divine, as Euthyphro suggests in the dialogue (

Euthyph

. 3b, cf. Xen.

Mem

. 1.1.2). Moreover, there is evidence from the fourth century that the Athenian state, while ready enough to welcome foreign deities such as Bendis and Asclepius to official cult status, regarded the introduction of private cults as sufficiently dangerous to merit the death penalty. So any evidence that Socrates was seen as the leader of a private cult would indicate potentially very damaging prejudice against him. We have some hints of such evidence. In

Clouds

Socrates introduces Strepsiades to his ‘Thinkery’ in a parody of the ceremonies of initiation into religious mysteries (250–74), while a chorus of Aristophanes’

Birds

(produced in 414) describes Socrates as engaged in raising ghosts by a mysterious lake, and his associate Chaerephon, ‘the bat’ (one of the students of

Clouds

), as one of the ghosts whom he summons (1553–64). We have here the suggestion that Socrates is the leader of a coterie dabbling in the occult, and the episode of his trance at Potidaea, where he stood motionless and lost in thought for twenty-four hours (

Symp

. 220c-d) may have contributed to a reputation for uncanniness. While it may seem to us that the picture of Socrates as an atheistic natural philosopher fits ill with that of a spirit-summoning fakir, that dichotomy may not have seemed so apparent in the fifth century

BC

; and in any case we are concerned with a climate of thought rather than a precisely articulated set of charges. Socrates, I suggest, was seen as a religious deviant and a subverter of traditional religion and morality, whose corrupting influence had been spectacularly manifested by the flagrant crimes of some of his closest associates.

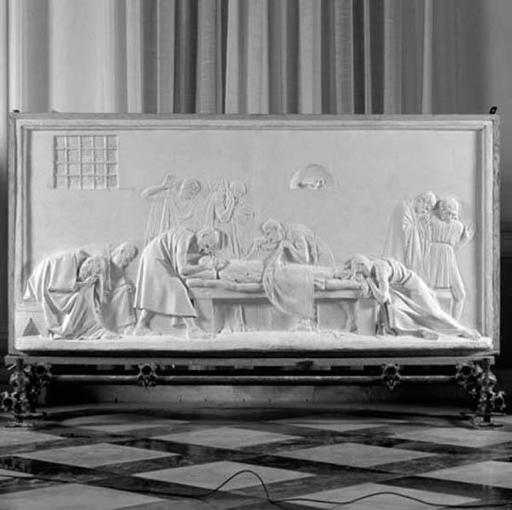

6. The Death of Socrates.

Crito Closing the Eyes of the Dead Socrates

(1787–92) by Antonio Canova.

So much for the case for the prosecution. As for the defence, though there was a tradition (which appears to go back to the fourth century

BC

) that Socrates offered none at all, the weight of the evidence suggests that he did indeed offer a defence, but one which was by ordinary standards so unusual as to give rise to the belief that he had not prepared it in advance, and/or that he did not seriously expect or even intend it to convince the jury (both in Xen.

Apol

. 1–8). (In all probability the story told by Cicero (

De oratore

1.231) and others that Lysias wrote a speech for the defence which Socrates refused to deliver as out of character indicates merely that a defence of Socrates was among the speeches attributed to Lysias; see [Plutarch]

Life of Lysias

836b.) It is natural to enquire how much of the substance of his defence can be reconstructed from the two versions which we possess, those by Plato and Xenophon. The two are very different in character. Plato’s, which is over four times as long, purports to be the verbatim text of three speeches delivered by Socrates, the first in reply to the charges, the second, delivered after his conviction, addressed to the question of penalty, and a final address to the jury after their vote for the death penalty. Xenophon’s is a narrative, beginning with an explanation of Socrates’ reasons for not preparing his defence in advance, continuing with some purported excerpts (in direct speech) from the main defence and the final address to the jury, and concluding with some reports of things which Socrates said after the trial. There are also considerable differences in content. Both represent Socrates as replying in the main speech to the three counts of the indictment, but the substance of the replies is quite different. Xenophon’s Socrates rebuts the charge of not recognizing the gods of the city by claiming that he has been assiduous in public worship; he takes the charge of introducing new divinities to refer only to his divine sign, and replies by pointing out that reliance on signs, oracles,

etc.

is an established element in conventional religion. The charge of corruption is rebutted primarily by appeal to his acknowledged practice of the conventional virtues, backed up by his claim (admitted by Meletus) that what is actually complained of is the education of the

young, which should rather be counted benefit than harm. The tone throughout is thoroughly conventional, to such an extent that the reader might well be puzzled why the charges had been brought at all.

Plato’s Socrates, by contrast, begins by claiming that the present accusation is the culmination of a process of misrepresentation which he traces back to Aristophanes’ caricature, in which the two cardinal falsehoods are (i) that he claims to be an expert in natural philosophy and (ii) that he teaches for pay. (In rebutting the second point he contradicts Xenophon’s Socrates in denying that he educates anyone.) In response to the imagined question of what in his actual conduct had given rise to this misrepresentation he does indeed claim that it is possession of a certain kind of wisdom. The explanation of what this wisdom is takes him far beyond Xenophon’s Socrates, since it involves nothing less than a defence of his whole way of life as a divine mission, but one of a wholly unconventional kind.

This mission was, according to Plato’s Socrates, prompted by a question put by his friend Chaerephon to the oracle of Apollo at Delphi. Chaerephon asked whether anyone was wiser than Socrates, to which the oracle replied that no one was. Since Socrates knew that he possessed no expertise of any sort, he was puzzled what the oracle could mean, and therefore sought to find someone wiser than himself among acknowledged experts (first of all experts in public affairs, subsequently poets and craftsmen). On questioning them about their expertise, however, he found that they in fact lacked the wisdom which they claimed, and were thus less wise than Socrates, who was at least aware of his own ignorance. He thus came to see that the wisdom which the oracle had ascribed to him consisted precisely in this awareness of his ignorance, and that he had a divine mission to show others that their own claims to substantive wisdom were unfounded. This enterprise of examining others (normally referred to as ‘the Socratic elenchus’, from the Greek

elenchos

, ‘examination’), which was the basis of his unpopularity and consequent misrepresentation, he

later in the speech describes as the greatest benefit that has ever been conferred on the city, and his obligation to continue it in obedience to the god as so stringent that he would not be prepared to abandon it even if he could save his life by doing so.

This story poses a number of questions, of which the first, obviously, concerns the authenticity of the oracle. Is the story true, or, as some scholars have suggested, is it merely Plato’s invention? There are no official records of the Delphic oracle against which we can check the story; the great majority of the oracular responses which we know of are mentioned in literary sources whose reliability has to be considered case by case. The fact that Xenophon too mentions the oracle is no independent evidence, since it is quite likely that he wrote his

Apology

with knowledge of Plato’s, and it is therefore possible that he took the story over from him. Certainty is impossible, but my own inclination is to think that the story is true; if it were not, why should Plato identify Chaerephon as the questioner, rather than just ‘someone’, and add the circumstantial detail that, though Chaerephon himself was dead by the time of the trial, his brother was still alive to testify to the truth of the story? More significant than the historicity of the story is the different use which Plato and Xenophon make of it. According to Xenophon what the oracle said was that no one was more free-spirited or more just or more self-controlled than Socrates, and the story then introduces a catalogue of instances of these virtues on his part, in which wisdom is mentioned only incidentally. According to Plato what the oracle said was that no one was wiser than Socrates, and Socratic wisdom is identified with self-knowledge. Xenophon uses the story to support his conventional picture of Socrates’ moral virtue, Plato to present Socratic cross-examination as the fulfilment of a divine mission and therefore as a supreme act of piety.

Another striking feature of Plato’s version of the oracle story is the transformation of Socrates’ quest from the search for the meaning of the oracle to the lifelong mission to care for the souls of his

fellow-citizens by submitting them to his examination. By 23a the meaning of the oracle has been elucidated: ‘In reality god [i.e. god alone] is wise, and human wisdom is worth little or nothing…He is the wisest among you, 0 humans, who like Socrates has come to know that in reality he is worth nothing with respect to wisdom.’ But this discovery, far from putting an end to Socrates’ quest, makes him determined to continue it: ‘for this reason I go about to this very day in accordance with the wishes of the god seeking out any citizen or foreigner I think to be wise; and when he seems to me not to be so, I help the god by showing him that he is not wise.’ Why is Socrates ‘helping the god’ by showing people that their conceit of wisdom is baseless? The god wants him to reveal to people their lack of genuine wisdom, which belongs to god alone; but why? It was traditional wisdom that humans should acknowledge their inferiority to the gods; dreadful punishments, such as Apollo’s flaying of the satyr Marsyas for challenging him to a music contest, were likely to be visited on those who tried to overstep the gulf. But the benefits accruing from Socratic examination are not of that extrinsic kind. Rather, Socrates’ challenge is to ‘care for intelligence and truth and the best possible state of one’s soul’ (29e), since ‘it is as a result of goodness that wealth and everything else are good for people in the private and in the public sphere’ (30b). There is, then, an intimate relation between self-knowledge and having one’s soul in the best possible state; either self-knowledge is identical with that state, or it is a condition of it, necessary, sufficient, or perhaps necessary and sufficient. That is why no greater good has ever befallen the city than Socrates’ service to the god.

The details of the relation between self-knowledge and the best state of the soul are not spelled out in the

Apology

. What is clear is that here Plato enunciates the theme of the relation between knowledge and goodness which is central to many of the dialogues, and that that theme is presented in the

Apology

as the core of Socrates’ answer to the charge of not recognizing the gods of the city. Unlike Xenophon,

Plato says nothing about Socrates’ practice of conventional religious observance, public or private. Instead he presents the philosophic life itself as a higher kind of religious practice, lived in obedience to a god who wants us to make our souls, that is, our selves, as perfect as possible. Each author has Socrates reply to the charge in the terms of his own agenda, Xenophon’s of stressing Socrates’ conventional piety and virtue, Plato’s of presenting him as the exemplar of the philosophic life.

Plato’s version of the replies to the other charges shows the power of Socratic questioning. The charge of introducing new divinities is rebutted by inducing Meletus to acknowledge under cross-examination that his position is inconsistent, since he maintains both that Socrates introduces new divinities and that he acknowledges no gods at all, while the charge of corruption is met by the argument that if Socrates corrupted his associates it must have been unintentionally, since if they were corrupted they would be harmful to him, and no one harms himself intentionally. As the latter thesis is central to the ethical theses which Socrates argues for in several Platonic dialogues, we see Plato shaping his reply to the charges against Socrates by reliance, not merely on Socrates’ argumentative technique, but also on Socratic ethical theory. Plato sees the accusation of Socrates as an attack, not just on the individual, but, more significantly, on the Socratic practice of philosophy, which is to be rebutted by showing its true nature as service to god and by deploying its argumentative and doctrinal resources. Xenophon’s reply, by contrast, has little if any philosophical content.

It is clear, then, that the hope of reconstructing Socrates’ actual defence speeches at the trial by piecing together the evidence of our two sources is a vain one, since each of the two presents the defence in a form determined by his own particular agenda. The question of whether any particular statement or argument reported by either Plato or Xenophon was actually made or used by Socrates seems to me

unanswerable. Looked at in a wider perspective, it seems to me that Plato’s version may well capture the atmosphere of the trial and of Socrates’ defence more authentically than Xenophon’s, for two reasons. First, the prominence which Plato gives to Aristophanes’ caricature and its effects (entirely absent from Xenophon’s version) sets the accusation in its historical background and gives much more point to the accusations of religious nonconformity and innovation than does Xenophon. Secondly, the presentation of Socrates’ elenctic mission as service to the god and benefit to the city expresses much better than Xenophon’s bland presentation the unconventional character of Socrates’ defence, and, ironically enough, displays much more forcefully than his own version the arrogance which he says all writers have remarked on and which he sets out to explain.