Smuggler Nation (45 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Another parallel to alcohol prohibition was the spread of drug-related corruption. The high profits of the trade not only enriched smugglers but also made bribes and payoffs to law enforcement an affordable business expense. Investigations following the fatal shooting of Arnold Rothstein in 1928 revealed not only the magnitude of his illicit drug import business but also the extent of drug corruption. A New York grand jury found that federal drug enforcement in the city—home to

the largest number of agents in the country—was plagued by gross incompetence, negligence, and corruption. Most embarrassing was the revelation that both the son and son-in-law of the deputy commissioner of prohibition, Levi Nutt, were actually employed by Rothstein.

41

America’s First Drug Czar

The New York corruption investigation following Rothstein’s death contributed to the shakeup of the federal narcotics bureaucracy and its separation from the much-maligned Prohibition Bureau. Efforts in Congress to establish an independent drug-control agency paid off in July 1930, with the creation of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) in the Treasury Department. With Nutt’s career derailed by scandal, President Hoover turned to Harry Anslinger, a high official in the Prohibition Bureau with considerable international experience targeting alcohol smuggling, and appointed him as the FBN’s first commissioner.

42

Figure 14.3 Federal Bureau of Narcotics Commissioner Harry J. Anslinger, America’s first “drug czar,” examines seized drugs in the 1950s (DEA Museum).

Anslinger became the J. Edgar Hoover of drugs, America’s first “drug czar.” During his more than three decades on the job, Anslinger never wavered from his commitment to a tough law-and-order approach to drugs. Anslinger told judges to “jail offenders, and then throw away the key.”

43

In his view, the main lesson to be learned from the failures of Prohibition was that it had not been tough enough. He believed that the key challenge was curtailing the drug supply, especially from abroad. As the top U.S. diplomat on drug issues, Anslinger played a lead role in international meetings and conferences concerned with narcotics, continuously lobbying for the increasingly restrictive measures that came to define the emerging global drug prohibition regime. He also spearheaded international efforts to coordinate drug-related intelligence gathering and sharing.

Because of their compact size and low weight relative to value, smuggled drugs were much harder to detect than smuggled alcohol. This made random searches of people, luggage, and cargo even more inefficient than during the Prohibition years. Anslinger therefore increasingly turned to informants and undercover operations to develop cases and make busts. He consequently “plunged the bureau into the murky business of employing smugglers to catch smugglers,” note historians Kathryn Meyer and Terry Parsinnen, with the downside that “using informants brought the agents into the same dark shadowlands as the traffickers they sought to control. At times their identities blurred.”

44

Yet for decades Anslinger turned a blind eye to the spreading rot of corruption within his own agency—which would eventually contribute to its dismantling and reorganization. An investigation initiated decades later found that nearly sixty out of the three hundred FBN agents were corrupt, which included collaborating with traffickers and selling heroin. Ramsey Clark, the U.S. attorney general at the time of the corruption investigation, concluded: “The least you can make of it is that Anslinger was derelict in being so unaware of what was happening in his own agency. Apparently he had decided as a matter of self preservation not to address it.”

45

Meanwhile, to generate the needed support to protect and expand his agency and its mission, Anslinger undertook a sweeping and aggressive campaign in the 1930s and 1940s to mold public antidrug attitudes.

He regularly testified before Congress and became a prolific writer, spreading his antidrug message through all types of media outlets. He persistently blamed particular minority groups, foreigners, and foreign ideological influences for America’s drug problem.

46

He aggressively cultivated a rising chorus of demands from sources from within and outside of government that argued for punitive sanctions against the sale and use of opiates and cocaine. Out of this increasingly moralistic and drug-intolerant social context emerged the criminalization of another drug: marijuana.

Killer Weed

Early drafters of the Harrison Act tried to outlaw marijuana but found little organized support for their efforts—and much opposition from the pharmaceutical industry.

47

By the mid-1920s, however, fear of marijuana was growing in the South and West, spurred by rapidly increasing Mexican migration. Although employers welcomed Mexicans as a source of cheap labor, the new immigrants—like the Chinese and others before them—triggered fears of crime and social corruption.

Racist and nativist suspicions about Mexican immigrants came to focus on marijuana use. Before long, local residents had attributed crime-producing powers to the drug. As the Great Depression made the Mexicans an unwelcome surplus labor force in the 1930s, the identification of Mexicans with both crime and marijuana deepened. Pressure on Washington to “do something” mounted from several quarters, including local police forces, citizens’ groups, state governors, and the Hearst newspaper chain (whose stories and cartoons detailed the ways the drug enslaved its users).

With his agents already plenty busy, Anslinger was at first reluctant to add marijuana to his list of targets. But by 1936 he had joined the push for federal legislation prohibiting it. He and his agency helped forge a more punitive public consensus against marijuana, and they assisted in crafting and securing passage of legislation and lent vocal support in the debate in Congress. In December 1936, Anslinger told Congress that marijuana was “about as hellish as heroin.”

48

Everyone seemed to have forgotten that just a year earlier he had claimed marijuana wasn’t even addictive.

The Marijuana Tax Act passed in the summer of 1937 and took effect in October of that year. By that time forty-six states had placed antimarijuana laws on the books. The Marijuana Tax Act was modeled on some features of the 1914 Harrison Act. Only the nonmedical, untaxed possession or sale of marijuana was outlawed. “Illegitimate transfers” were taxed at $100 a pound—a steep tax considering that marijuana purchased legally cost $2 a pound. Violations brought a fine of $2,000, five years in prison, or both.

49

The antimarijuana campaign had succeeded in adding the substance to the public’s list of serious law-enforcement threats: by the time marijuana was outlawed, “common sense” linked its use to deadly crimes. A person under the influence of marijuana could, as Anslinger put it, be provoked by “the slightest opposition, arousing him to a state of menacing fury or homicidal attack. During this frenzied period, addicts have perpetuated some of the most bizarre and fantastic offenses and sex crimes known to police annals.”

50

Little

opposition surfaced to Anslinger’s efforts to define marijuana as a crime-causing “killer weed” and to ban its use; and in the fearful and moralistic mood of the day, few spoke out against the general trend toward a punitive policy of drug prohibition. The government discouraged opposition by blocking critical testimony, disparaging those who publicly questioned policy assumptions, studiously ignoring contrary evidence, and straining to defend the many questionable claims about drugs propounded by prohibitionists and the media.

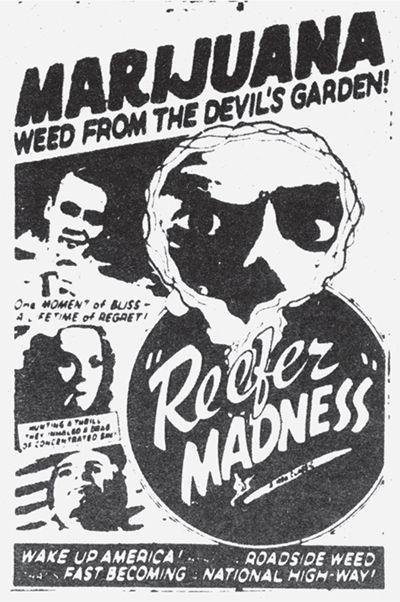

Figure 14.4 Advertisement for the 1936 American film

Reefer Madness

. Decades later it was used by the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws to illustrate the excesses of the antimarijuana campaign (Granger Collection).

If few questioned the criminalization of marijuana, almost no one challenged the basic assumptions of Anslinger’s overall drug-suppression strategy. The only outspoken opposition in Congress in the 1930s and 1940s came from Washington representative John M. Coffee. Coffee pointedly condemned the Harrison Act and the federal government for creating a vast smuggling industry: “If we, the representatives of the people, are to continue to let our narcotics authorities conduct themselves in a manner tantamount to upholding and in effect supporting the billion-dollar drug racket, we should at least be able to explain to our constituents why we do so.” He argued for going back to the original intent of the Harrison Act, bringing addicts under medical supervision to secure the supply they needed legitimately at low cost: “Morphine which the peddler sells for a dollar a grain would be supplied, of pure quality, for 2 or 3 cents a grain. The peddler, unable to meet such a price, would go out of business—the illicit narcotic drug industry, the billion-dollar drug racket, would automatically cease to exist.”

51

Such appeals fell on deaf ears—much to the delight of both drug smugglers and drug law enforcers.

Drugs and Geopolitics

The emerging illicit drug trade was shaped not only by prohibitions but also by geopolitics. As the United States became a dominant player on the world stage, drugs and national security increasingly bumped into each other—at times awkwardly, but also in politically useful ways. Geopolitics trumped drug enforcement during and after World War II, often to the advantage of politically protected traffickers. At the same time, anticommunist anxieties provided added ideological ammunition for America’s antidrug campaign. In other words, the United States

overlooked drug trafficking when geopolitically convenient, while also disparaging geopolitical rivals as complicit in the drug trade.

Anslinger cultivated close relations with the intelligence community, and he was pleased to have the FBN’s surveillance capacities put to good use during the war years when the illicit drug trade had largely dried up with the disruptions in global transportation. For instance, Garland Williams, the head of the FBN’s New York office, became director of special training at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, predecessor of the CIA). Similarly, FBN agent George Hunter White was appointed as director of counterespionage training at the OSS. After the war, the FBN jointly operated safe houses with the CIA in New York and San Francisco, provided CIA operatives with FBN jobs as cover overseas, and even collaborated on mind-control drug research experiments.

52

Not just drug-control agents but also drug traffickers were recruited in the pursuit of American war objectives. Most notable was the case of Charles “Lucky” Luciano, who had made a name for himself as a bootlegger and also engaged in heroin trafficking and organized prostitution. Arnold Rothstein’s illicit drug import business passed on to Luciano and other underlings in the New York underworld, such as Meyer Lansky, Louis Buchalter, and Frank Costello.

53

In 1936 Luciano began a long prison sentence for running a New York prostitution ring. World War II proved to be the break that gave him his get-out-of-jail-free card; he was pardoned and deported to freedom in Italy in 1946 as a reward for his wartime collaboration with U.S. Naval Intelligence.

54

Luciano made a deal: using his business partner Lansky as a go-between, he agreed to gather intelligence from his contacts in New York’s waterfront underworld to protect the city’s harbor against German espionage and sabotage, and also use his mafia contacts in Italy to help prepare the way for the 1943 American invasion of Sicily. It remains unclear how useful Luciano’s information actually proved to be. In any case, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover was stunned when he heard about it: “This is an amazing and fantastic case,” he wrote in a memo. “We should get all the facts, for it looks rotten to me from several angles.” When informed that the Office of Chief of Naval Operations “acknowledges that Luciano was employed as an

informant,” Hoover called it “A shocking example of misuse of Navy authority in interest of a hoodlum. It surprises me they didn’t give Luciano the Navy Cross.”

55