Smuggler Nation (18 page)

Authors: Peter Andreas

Tags: #Social Science, #Criminology, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Perhaps most importantly, the War of 1812 should be remembered for what it failed to do: conquer Canada. Hugely consequential, this non-event has nevertheless long been forgotten (along with the war itself) in the popular imagination in the United States, but certainly not in Canada. Massive smuggling was just one of the factors that undermined American territorial ambitions during the war, but it was certainly the most embarrassing and even scandalous. During the war, it is fair to say that Canadians and Americans proved far more interested in illicitly trading than in fighting with each other, and indeed trade would continue to be the defining feature of their relationship for the next two centuries.

As for the Laffites, it is perhaps ironic that they contributed to a victory that led to the strengthening of government authority—including a beefed-up U.S. naval presence in the Gulf—making the area less hospitable for their illicit business. The Laffites subsequently moved their base of operations further west, to the more remote Texas coast in Mexico beyond the reach of U.S. authorities. But they would never again experience the same profitable opportunities that the embargo and war years provided in New Orleans and the Mississippi River Valley.

71

Although historians continue to debate the significance of the role of the Laffites and the Baratarians in the battle of New Orleans, Louisianans have immortalized Jean Laffite’s contribution to the state’s history by naming a 20,020-acre park and wildlife preserve the “Jean Laffite National Historical Park and Preserve.” The city of Lake Charles, Louisiana, also puts on an annual festival, appropriately named Contraband Days, in honor of Jean Laffite.

6

The Illicit Industrial Revolution

THE AMERICANS NOT ONLY

fought the British on the battlefield and on the high seas but also systematically stole from them as part of the nation’s early industrialization strategy. Although typically glossed over in the sanitized accounts found in U.S. high school textbooks, as a young and newly industrializing nation the United States aggressively engaged in the kind of intellectual property theft it now insists other countries prohibit and crack down on. So we now turn to examine how America became such a hotbed of intellectual piracy and technology smuggling in its adolescent years, particularly in the textile industry. Only after it had become a mature industrial power did the country vigorously campaign for intellectual property protection—conveniently overlooking its own illicit path to industrialization.

1

In the aftermath of the American Revolution, the smuggling of industrial technologies into the new republic was the one form of smuggling still viewed as unquestionably patriotic—especially since Great Britain was the main target. Indeed, it was encouraged and celebrated as essential to building the new nation and reducing its dependence on old colonial masters. It wasn’t usually called “smuggling,” but this is certainly what it was. It was also not called “intellectual piracy,” as it is today, but it was certainly a form of theft.

Illicit industrialization involved both smuggled machinery and smuggled migrants with the skills, knowledge, and expertise to assemble and operate the equipment. There was an overwhelming demand for both in the early years of the nation. Smuggled machinery violated British export laws. Smuggled migrants—which really meant self-smuggling even if sometimes involving aggressive recruiting by covert American agents abroad—violated British emigration laws. The two were closely intertwined. After all, the illicitly obtained machinery was of no use if no one knew how to use it. In this regard, the machinist was more valuable than the machine: ideally, he could not only re-create but also improve upon the original design. British prohibitions slowed the clandestine outflow of brainpower and technology but ultimately failed to stop it. By 1825, cotton textile production was entirely mechanized, with the United States “only slightly trailing, if at all, Britain in the adoption of power weaving.”

2

By midcentury, the United States had become one of the world’s leading industrial powers.

A Backward but Ambitious New Nation

The United States emerged from the Revolutionary War acutely aware of Europe’s technological superiority. But it also had enormous ambitions and aspirations to rapidly catch up and close the technology gap. The acquisition of new industrial technologies from abroad, it was hoped, would help solve the country’s chronic labor shortage and enhance its economic self-sufficiency and competitiveness. As the

Pennsylvania Gazette

put it in 1788, “Machines appear to be objects of immense consequence to this country.” It was therefore appropriate to “borrow of Europe their inventions.”

3

“Borrow,” of course, really meant “steal,” since there was certainly no intention of giving the inventions back.

The most candid mission statement in this regard was Alexander Hamilton’s

Report on Manufactures

, submitted to the U.S. Congress in December 1791.

4

The secretary of the treasury argued that “To procure all such machines as are known in any part of Europe can only require a proper provision and due pains. The knowledge of several of the most important of them is already possessed. The preparation of them here is, in most cases, practicable on nearly equal terms.”

5

Notice

that Hamilton was not urging development of indigenous inventions to compete with Europe but rather direct procurement of European technologies through “proper provision and due pains”—meaning, breaking the laws of other countries.

6

As the report acknowledged, most manufacturing nations “prohibit, under severe penalties the exportation of implements and machines which they have either invented or improved.”

7

At least part of the

Report on Manufactures

can therefore be read as a manifesto calling for state-sponsored theft and smuggling.

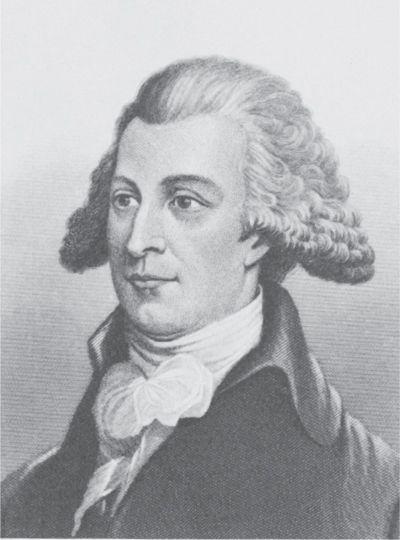

Hamilton appointed Tench Coxe as assistant secretary of the treasury and tasked him with writing the initial draft of the report. Coxe was one of the most well-known and outspoken advocates for illicitly acquiring European manufacturing technologies, and personally invested in several technology-smuggling schemes.

8

He was a spokesman for the

Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Useful Arts, which early on helped turn Philadelphia into the nation’s leading center for acquiring foreign technologies and the artisans to operate them.

9

Figure 6.1 Tench Coxe (1755–1824), a leading proponent of industrializing through the clandestine importation of British machinery and machinists. Coxe served as assistant secretary of the treasury when Alexander Hamilton was secretary of the treasury, and he wrote the

Report of Manufacturers

with Hamilton (Granger Collection).

Other American statesmen were equally enthused about illicitly acquiring European industrial technologies, even if they were less public than Hamilton and Coxe in advocating official government sponsorship. After all, doing so entailed violating the export laws of another country and was thus diplomatically awkward and delicate, to say the least. Benjamin Franklin, for instance, enthusiastically encouraged British artisans to violate British emigration laws and come to America, providing letters of introduction to facilitate the move—but was reluctant to provide material assistance and inducements.

10

George Washington was also a strong supporter of acquiring European manufacturing technologies, but as president he was wary of the reputational consequences of appearing directly complicit in such illicit schemes. In January 1791 he explained why he was backing away from direct involvement in setting up a Virginia textile factory using smuggled machines. “I am told that it is a felony to export the machines, which it is probably the artist contemplates to bring with him,” Washington wrote to the governor of Virginia, Beverly Randolph, “and it certainly would not carry an aspect very favorable to the dignity of the United States for the President in a clandestine manner to entice the subjects of another nation to violate its laws.”

11

Nevertheless, the president had no qualms about encouraging others to do so. In his first State of the Union Address in January 1790, Washington declared, “I cannot forbear intimating to you the expediency of giving effectual encouragement as well to the introduction of new and useful inventions from abroad.”

12

The first U.S. Patent Act and its subsequent revisions reflected the government’s eagerness both to adopt new technologies through any means and also to maintain the appearance of upholding the rule of law. At least on paper, the patent law of 1790 protected inventors. But as historian Doron Ben-Atar explains: “this principled commitment to absolute intellectual property had little to do with reality. Smuggling technology from Europe and claiming the privileges of invention was quite common and most of the political and intellectual elite of the

revolutionary and early national generation were directly or indirectly involved in technology piracy.”

13

The revised U.S. Patent Act of 1793 required patent applicants to take an oath certifying that their invention was original, but the administrator of the patents did not even insist that the oath be taken. The Patent Board lacked the will and the capacity to check the originality of patent requests.

14

Moreover, the Patent Act did not protect foreign inventors; they could not obtain a U.S. patent on an invention they had previously patented in Europe. In practice, this meant that one could steal a foreign invention, smuggle it to the United States, and develop it for domestic commercial applications.

15

The patent registration system “allowed wealthy importers of European technology, such as the Boston Associates, to claim exclusive rights to imported innovations and use the courts to validate their claims and intimidate competitors.”

16

In other words, the law could be used to protect lawbreaking. Through its discriminatory patent rules, America became the world’s most notorious haven for industrial piracy.

17

Especially sought after—and especially protected—were the new textile manufacture technologies. “Strange as it may appear,” observed Coxe, “they also card, spin, and even weave, it is said, by water in the European manufactories.”

18

In the 1750s, historian Carroll Pursell reminds us, textile production still remained largely a medieval enterprise based on manual labor. It had not substantially changed for centuries but was suddenly revolutionized in just a few decades with the introduction of mechanical power. In Britain, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny in 1764 and patented it in 1770; Richard Arkwright patented his water frame in 1769 and a carding engine in 1775. Around the same time, Samuel Crompton created his mule (integrating the tasks of the water frame and the jenny). These various machines all performed the same key task of turning cotton fiber into thread. In 1790, England was the only country in the world with the technology to spin yarn by waterpower. But that was about to change.

19

Indeed, by mid-1791, note Anthony F. C. Wallace and David J. Jeremy, there were already copies of Arkwright’s water frame, Hargreaves’s jenny, and perhaps even Crompton’s mule in America, and the British were launching a “clandestine counterintelligence operation to recover them. Several British agents or patriotic merchants were buying the American machines wherever possible and shipping them

back to England, and, in some instances, when the machines could not be procured, allegedly burning down the factories that contained them. And American agents—some of them secretly financed by the secretary of the Treasury—kept on bringing in more plans, more models, and more English mechanics.”

20