Small Man in a Book (18 page)

Read Small Man in a Book Online

Authors: Rob Brydon

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

For one of his classes I memorized and performed the opening page or so of

The Catcher in the Rye

. I sat, or maybe leaned, against the classroom wall and stared down at my feet and out of the window, taking a while before I began, ‘If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know …’ I was pleased with how it went; I’d tried to make it as naturalistic as possible, a low-key performance like those of my cinema heroes. I was thrilled when John said how much he’d liked it, and that a sign of how good it had been was the fact that he didn’t know I’d started. I don’t think I gave another performance that natural and unforced until

Marion and Geoff

, fifteen years later.

Alongside James I became very friendly with another student, an altogether different type of personality. Dougray Scott was not Dougray Scott in those days; he was Stephen Scott (the name was changed out of necessity when he joined the actors’ union, Equity). Dougray was an intense young man whose natural talent, drive and good looks marked him out to me as winner of the ‘most likely to succeed’ competition. We bonded over a shared love of that holy trinity of actors, Hoffman, Pacino and De Niro, and an appreciation of Arthur Miller’s masterpiece

Death of a Salesman

. Like my dad, Dougray’s father had been a salesman, and the play resonated deeply with both of us. We would read it to each other and talk of one day playing the sons, Biff and Happy, together on the stage. It never happened – and now we’re too old. I’d still like to do the play, and so would he; it’ll be interesting to see who’s first to show their Willy. Forgive me.

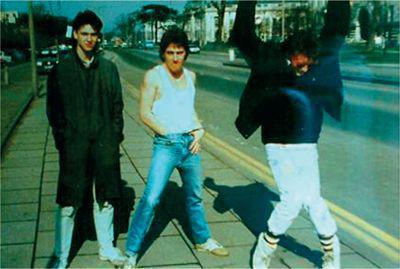

With Dougray and James in Cardiff. I appear to be searching for my keys.

Dougray was very much a devotee of ‘the method’ and by his own admission went through college ‘like a tortured young artist’ while I ‘breezed through it, destined to make people laugh’. In improvisation classes our different approaches to our craft were evident. When asked to observe an animal and then present our interpretation to the class, Dougray spent all his spare time in the park, notebook in hand, studying the pigeons. He arrived in class and gave us his pigeon; it was a very intense, beautifully nuanced pigeon. It may have been one of the pigeons from

On the Waterfront

, with maybe just a slight hint of one of the doves from the wedding scene in

The Godfather

. I had done no preparation at all, but entered into a lively impersonation of our dog at the time, a Yorkshire terrier named Purdey. I jumped up and down, yapping excitedly, much to the delight of our teacher, who praised my diligence and remarked that I’d obviously spent many hours studying the creature. I nodded sagely in agreement, while making a mental note that you can indeed fool some of the people some of the time.

Along with James and Dougray, my main friendships were with David Broughton Davies and John Golley. Dave was a Welshman from Wrexham and, at twenty-six, a little older than the rest of us. This age difference gave him the air of a man who had already lived his life and had come to college as a project to see him through his retirement. He had begun his working life as a civil servant for nine years, before turning his back on the security and heading off to drama school. He shared my love of Springsteen and had his own collection of bootleg cassettes, which we would listen to religiously. Dave stood out for many reasons: his age, his ever-so-slightly-portly frame, his generally upbeat nature, and the fact that he owned a car. It might have been the worst car I’ve ever known – an appalling black Fiat Panda that seemed to be made of the material used to make fizzy-drink cans. It was also the best car I had ever known, by simple virtue of the fact that it was there and Dave was very generous in his use of it. Dave was very generous, full stop. He was always encouraging me and making me feel that I was a little bit more talented than was necessary. He seemed to love college life too – partly, I’m sure, because he’d known what it was to work in an ‘ordinary’ job. College must have seemed a breeze by comparison.

Dave also had a girlfriend, a fellow student called Debbie. My memory of Debbie is that she came from London and had quite a hard, cynical edge. The three of us were in a pub one night talking about another student when Debbie said, ‘Yeah, well, he’s all right but I wouldn’t part my legs for him.’ As ridiculous as it sounds, I was rather shocked by her remark; I’d certainly never heard a girl speak like this before. If I’d been holding a cup of tea to my lips, it would have been the perfect moment to pay tribute to Terry Scott and spit it out.

Dave lived in a big house on Llandaff Road, which he shared with James and also John Golley. John is a very easy man to describe. Picture David Bowie in his Thin White Duke period and you’re almost there. John was the epitome of cool, and his room, as was the case with all of us, was the perfect representation of his personality. It was an eaves room at the top of the house with little or no clutter. A row of carefully arranged cassettes, a hairdryer and a vintage Gretsch guitar are all I can remember. As wonderful as the guitar was, I don’t recall ever seeing him play it. He would laugh at my jokes with the easy air of an indulgent uncle whilst, in the corner of his mind, calculating the details of his next sexual conquest. Thinking again of his room, I would describe it as a Zen temple of benign narcissism and sex.

Number 186 Llandaff Road was a welcoming environment. It had a sense of community that my own digs in Oakfield Street lacked, with their strictly enforced immersion heater rules and cold-water kitchen facilities. It turned out that the music student who had brought me there in the first place was a practising Christian Scientist. This only came to light when he went down with a very heavy cold but refused to take any kind of medication. He survived, although he was very poorly for some time (during which I went in his place to see Level 42 at the university with his girlfriend, so the tickets wouldn’t go to waste).

Llandaff Road was always buzzing. James had an electric keyboard, as well as an upright piano and a toasted sandwich maker. This splendid machine was never off. James would pile in as many ingredients as the thing would take, most notably ham and cheese. James’s cheese of choice was Edam, a new experience for me; until then my cheese life began and ended with Dairylea. It was while eating toasted sandwiches that I introduced James to Bruce Springsteen, an artist whom he had yet to encounter, content as he was with Noël Coward, Cole Porter et al. After munching the sandwiches, we would sing together. James would work out the chords to songs by Bruce and Elvis, and I would wail away to my heart’s content.

As time went by, these evenings became more frequent and eventually we would find ourselves slipping away during free periods at college up to the top floor where the music department’s practice rooms were to be found. These were tiny cells, just big enough for an upright piano and a chair; there was certainly no way they could accommodate the circular transit of a dead cat. James and I would walk along the corridors and glance in through the little oblong window in each door until a vacant room was found. Then we’d slip inside and work through our favourite songs. Anyone walking past would have been perplexed at the sudden change from Elgar to Elton John. They would have considered the college to be rather progressive – or perhaps catering for children with learning difficulties.

As we pressed on with our practices, they began to take on the feel of rehearsals, and so we decided to put on a show. The ‘show’ consisted of a big, overblown, over-generous, expectation-raising introduction from one of our fellow students followed by James and me, under the title of Rob and James, rattling through a collection of songs. James banged away at the piano while I cavorted with the microphone, hoping to summon the spirit of Jim Morrison as I writhed and spun amongst the assembled crowd in the student bar. It’s safe to say that the Lizard King’s spirit remained unevoked – beyond, perhaps, an irritable turning in his grave. The performance was not so much Jim Morrison as Jim Carrey. I suspect I brought to mind a mid-period Bruce Forsyth. And yet despite or perhaps, to be fair to Brucie,

because

of this, we went down a storm.

We were soon known as a double act, spoken of throughout the college with some affection, and with almost indecent haste we landed our first broadcast gig. We were called into our head of year’s office one day and told that BBC Radio Wales, based just up the road in Llandaff, were looking for local acts to take part in a live radio show, in front of an audience. Would we like to give it a go and try out for a spot? It amazes me now to think that we didn’t hesitate for a moment; we jumped at the chance. We can only have done two or three public performances at this point, but that didn’t stop us from taking the bit between the teeth and trotting on towards potential humiliation.

It transpired that we had to complete not one but several auditions to win a spot on

Level Three

. It was a magazine-style show on BBC Radio Wales, which was broadcast live each Friday morning from the recently opened St David’s Hall in Cardiff. In a classic example of the psyche of the performer (years later, an agent would enlighten me with his opinion that all performers are in possession of high ego and low self-esteem) I was simultaneously overawed and tremulous at climbing the steep and imposing steps that led to the mighty BBC Wales, and appalled that we were having to audition more than once for what was essentially a local radio show.

My memory now projects a sepia-tinted silent movie of James and I playing and singing our hearts out in a vast, cavernous studio along the lines of the fabled Abbey Road. I think I’ve fallen victim here to the

Vanilla Sky

scenario whereby Tom Cruise’s memories (or manufactured reality/lucid dream) are made up largely of the pop-culture influences he has absorbed during his lifetime, as opposed to any actual reality. I now know that the studio wasn’t all that big; my memory has allowed all the biopics of struggling artists, and the documentaries on the making of classic albums that I’ve seen, to seep in and corrupt my consciousness. This must explain why, when thinking of our audition for Radio Wales, I can remember Paul Simon in a far corner of the room, becoming increasingly irate with Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

We decided that we would audition in character, with me playing the role of Tony Casino. Tony was a Welsh nightclub singer who thought of himself as Tom Jones but in reality was sadly lacking in every department. I can’t claim that Tony was a masterpiece of observational comedy or, for that matter, a stinging satire on the state of light entertainment; he was basically me with a more pronounced Welsh accent. We went through our collection of numbers: an upbeat ‘Amarillo’, a ludicrously French-accented ‘She’ (a nod of recognition here, surely, to Kenneth Williams and his ‘Ma Crêpe Suzette’) and finally, fresh from its success at the Swansea Camp Society audition, my moving interpretation of Lionel Richie’s ‘Hello’. We played them again and again for the producer of the show, Caroline Sarll, and her assistant, Siân Roberts, until finally we were given the nod and told that we’d made it onto the show.

Tony Casino and the Roulette Wheels

I’m playing down its significance now, but at the time this was a very big deal indeed – a live radio show, a live audience not made up of friends but of real people who would judge us entirely on merit. The Friday morning of the broadcast duly arrived. With time off from classes we set out for what was to be, for both of us, our first paid gig. I’m not sure how it is today, when it would seem that any sixteen-year-old with the slightest inclination towards performance can stick themselves up on YouTube with a potential audience of millions, and at the very least secure a regular role in

Hollyoaks

. In 1985, things were very different. Short of bellowing out of your bedroom window, you couldn’t broadcast yourself; you were always in the hands of others, and so the radio held an air of exotic inaccessibility. To my twenty-year-old self it represented a fair chunk of my dream pie.

I had for a long time held an above-average interest in the medium of radio, listening to it avidly and even hoping that one day I might myself become a disc jockey. My heroes were disappointingly predictable; when grouped together they effortlessly formed a list of solid, middle-class BBC-approved respectability. Names like Ed Stewart, Tony Blackburn and Noel Edmonds would have been high up the chart, although I also possessed a slightly more risqué (if that’s not too misleading a word, and I’m fairly certain that it is) fondness for some of the presenters on whistling and whiney Radio Luxembourg.