Sleight (16 page)

Authors: Kirsten Kaschock

Each one of our animals was an adoption. They were lost. They call it a system—my Ray worked in that system. That system, it didn’t work. We took them in, gave them spirits. Now they are strong. Proud. Beautiful. Free. They belong to Christ. Christ was the lamb. They are what they wanted to be: Christ’s. Ray asked them. Ray gave them choices not many animals get. They didn’t want to be what they were. Their hair, for example. I couldn’t use the hair of all but two. Those two had to do for every mane, every tail. We have eight lions and five horses. And now the bones are clean. You can’t tell anything at all from the bones. I’m very happy about how clean they came.

—transcripted from the Vogelsong tape as it aired on

Channel 8 News

The links were breathtaking. In all four chambers, members of Monk and Kepler were speaking with the architectures—invocations of animals that didn’t exist. A calling forth of alien life: sky-whale and tree-elk and earth-sparrow. Montserrat, Doug, Manny, and Yael joined a member of Kepler in a low structure. They alternated taking two small stutter-steps with a quick carving motion to make the floor swarm with skittering fish, then shot the structure overhead so that mice seemed to spiral along the architectures before moving up into the rafters. Strange mice, smooth as icing. Haley and a pair of Kepler’s men were lumbering gracefully—a two-trunked elephant clearing ground and air as if in preparation for the planting or burial of thought. Latisha and T were bound by their architectures in what seemed a vegetative embrace, until the link began to rotate, arcing them across the floor in a velvet bestial waltz. And they were all wicking. All of them—flashing in and out like the evening news in a July thunderstorm. There was an overpowering static to it, a haze in the chambers that lasted hours.

Kitchen and Clef weren’t themselves inside of it. They walked slowly, slowly between the chambers, disengaging each foot with care each time it left the floor. Mute. It was Kitchen silently crying. Clef, reaching for his hand. The second time they entered chamber two, they saw across the field of sleightists a man and a woman holding hands at the other entrance. This was not a mirror. This was Lark, but the man was white, not Drew. Between the couples, sleight was giving birth. Creature after creature tumbled forth in a discontinuous river of forms. A dumb show. Eden unnamed.

West watched, rotating through each of the four chambers from the office. A door and small tinted window on the fifth wall of each chamber led into the small gray room: file cabinet and telephone. There he had gone, to sit in the dark like a child, choosing the fauna of his next life.

20

The illusion of distance—the illusion of illusion—is created and maintained in sleight by the very theaters in which it is performed. Distance is necessary to transform what is terrifying into what is pleasurable. For the audience, wicking is an illusion. They cannot explain it; they adore not being able to, but they do not believe for one moment that the figures onstage actually flash out of existence. No, the location of sleight—the familiar, deceitful stage—assures them that they are being happily duped. The eventual reappearance of the sleightists similarly pacifies them. Any misgivings someone may have while watching her first sleight vanishes when she witnesses the habitual complacency of fellow theatergoers.

21

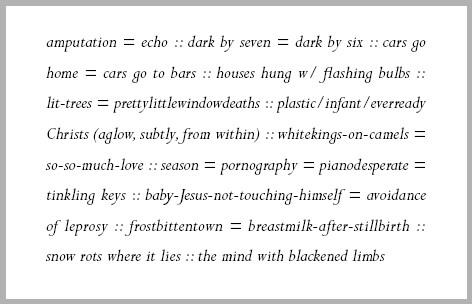

Sleight is stringently antinarrative. Hands have been summarily dismissed from the academy for storying up their precursors, subconsciously or otherwise. Called the

mathematics of performance

and

visual music,

sleight forges its content from the medium itself. Whatever the original reason for its abstraction, by remaining nonreferential, sleight is able to be universally interpreted by its audience. Directors know that the moment meaning is attached to intent (the hands’ or the sleightists’) is the exact moment the audience begins to feel inadequate—and withdraws. The form is all. Sleight’s function has always and only been the breeding, the perfection, the care and feeding of the form.

22

In the syntax of sleight, an architecture is a word. A manipulation is a single definition of an architecture; an architecture can be moved through several different manipulations—anywhere from three to thirty. A link is the method by which one architecture attaches to another. Links are phrases. A structure is a group of links that works together coherently: a sentence. When hands draw sleights, the structure is the most minute level they work with. Thus it is the director, not the hand, who chooses the architectures that best correspond to the structure on the page and then links them to create an approximation. The director is interpreter—wielding as much power as an interpreter chooses to wield. More. The product—the poem or the essay or the diatribe the director lifts out of the blueprint—is sleight. A hand, then, could be likened to a womb-deaf composer, arranging his notes not for instruments but solely in terms of color. It is the director and not the hand who transports prism to symphony.

23

Bugliesi began sleight with just under fifty architectures. Currently, there are sixty-odd institutionalized designs; preexisting ones are rarely altered—new ones are added to the official list at a rate of less than two per decade by a process both arduous and spuriously bureaucratic.

24

Unlike the system of rules provided for the structures and even the naming of sleights, the writing of precursors is a fairly unfettered practice. A hand must not create narrative, but no word is off limits, and there are no guidelines to suggest how a precursor might match language with form. Precursors are the intuition of sleight, its curve. Hands who fall into formula with their precursors inevitably effect redundant sleights.

25

Sleight is not routinely perceived as grotesque, despite its recorded adrenal effect: a heightened sense of threat. In a study done by Dr. G. T. Theva of the Hookings Medical Institute, puzzling chemical phenomena were documented in a third of the study’s participants—all seated audience members. Indeed, the number of heart incidents occurring in sleight theaters prompted managers to equip them with defibrillators far before it was fashionable. Beyond the effect Theva noted in its spectators, sleight has also been described as “a carnival of self-annihilation” and “a compulsive reenactment of the death-wish.” This is to say that, despite its continuing success with the general public, there are a minority who find sleight theoretically abhorrent.

NOVEMBER.

T

he first night back in York, Lark had joined Byrne in his bed—a simple platform with a thin, hard mattress, no springs—large enough for two people, if they made a concerted effort, not to touch. Byrne had fallen in love with her little girl. He liked Drew. And Lark loved Drew: they had a little girl. So Byrne and Lark had not slept together. Other than to sleep.

The second night, after a grueling day in the chambers, they came back and she, wordlessly, grabbed a flannel blanket from his one closet and curled into the sunken sofa Byrne had inherited from the landlord. The next morning, he took the top sheet from his bed and set it on the already-folded blanket. Lark spent the next four weeks, ten hours a day, working in the chambers. Twice, she’d said for him to go home without her, and she’d slept at the studio. A large, zebra-striped sectional dominated the Kepler lounge. Dizzying pattern—sleek, retro lines. He’d passed out there often enough during rehearsals. Daymares.

On several occasions he overheard Lark tell West she didn’t know how to begin drawing a sleight. She said it defiantly. And each time West answered, “Whatever you need.” So she trained. Byrne had been watching sleightists all his life, closely now for three months, and he had not seen anyone go at the practice—go at themselves—so ruthlessly.

Monk and Kepler would begin each day in chamber one, warming up. Some arrived a half hour before class, to prime their bodies for priming. Others came into the chamber only when called. Lark was among the former. In her unrelieved intensity, she stood out. Although the other sleightists worked through class in seeming unison, each focused on his or her unique body. Kitchen began his exercises loose and small, at a lower level and with eyes closed, for balance. Clef was nursing an ankle, lifting and circling her foot until the joint cracked or, alternately, bending her knee to elongate a powerfully articulated calf. T, easily the most flexible sleightist in Kepler, maybe Monk too, spent the mornings testing the outermost limits of her contortions. Byrne had noticed, previously, that although sleightists spent a great deal of time on the weak areas of their technique, they invested even more in pushing their strengths to summation. In this regard, Lark’s practice was different. Her effort nondiscriminatory. She applied equal energy to each exercise, each body part, each quality of movement. To watch her was to be exhausted. She might not be as talented as the others, he couldn’t tell, and certainly she was out of practice—but she saved nothing.

Sometimes Byrne would stand in the back first thing in his sweats, doing what he could, which wasn’t much. Spine articulations, grounding exercises, some joint release. Once they began the larger motor movements—stridings or redemptions or flailings

26

—he’d slip out the back, into his shoes, and head to Jersey’s for breakfast and to think, write. Lark didn’t eat breakfast, and she didn’t like his coffee. On the way in each day they stopped to get her something stronger. His hosting abilities were lacking, he wasn’t reciprocating her family’s generosity—but how could he? He wasn’t a family. He didn’t have the depth of bench for graciousness. He kept thinking she’d leave to stay with her sister, but Clef only had the motel room she shared with Kitchen, and Lark said Byrne’s was fine. When he came back from his Denver omelet each day, the sleightists were separated into three chambers, perfecting the animal work they’d begun just before he and Lark had arrived in York.

The pair had pulled into the parking lot that first afternoon, beat. They’d walked up to the dented steel door, the back entrance Byrne knew would be unbolted. Entering, covered in the film of a twelve-hour drive begun before dawn, they immediately sensed it—the multiple, nearly constant wicking. Though they could see nothing from the lounge, the air was charged, popping. They couldn’t look at each other. Making contact in that air would have been, Byrne thought, intolerable.

When Lark dropped her bag and keys onto the loud couch, he’d looked at her, but not into her face. Although the lounge was well heated—a blast of warmth had hit them when they’d come in—she’d grabbed herself, maybe to confirm she was still there. The air was fanatical. It was like the air at book burnings perhaps, or cockfights, maybe prisons. The air had color the way Lark’s Souls had it—erratic and palpable. It was how the air must have been at Marvel’s studio in Kenosha, when he was still making rent. His brother had asked him, more than once, but Byrne could never bring himself to go.

She’d stood, shaken her body from its cold pose, and moved toward the closest door—the door to chamber two. When Byrne didn’t follow, she walked over and took his hand, to lead him. Her fingers were articulate; whenever she spoke, they went to her head or fluttered and tapped one another, as if counting. He had imagined their touch: abrasive—a fine sandpaper. But they were water. She took his rock hand and together they entered the chamber. They’d stayed that way, watching the menagerie unfold. For an afternoon, they were statued witness—two hands enveloping stone. Flesh, grown around a pit.

Each day since, when the sleightists separated to work on the creatural links, Lark went to chamber four, kept open for her use. And after Jersey’s, Byrne went into the office to watch her. West was often there, laughing at him.

“T’s been missing you, Byrne.”

“T still has you, at least occasionally. She told me. She also has a husband.”

“As do many of the women who spark your interest, it would seem.”

“Screw you.”

“Screw whomever you like, as long as you’re writing.”

“I’m writing.”

“Good. It’s why I keep you around.”

West spent some of these weeks on the phone, putting the tour in order, doubling hotel arrangements and bus rentals to accommodate two troupes instead of one—they were to leave seven days into the new year. With the rest of the time, he observed the links, occasionally entering a chamber to suggest a different entrance into a structure, a different path through a manipulation. Byrne had known West was talented, but in these weeks he saw just how. West would walk into the room, take a sleightist aside, quietly conferring for a minute or two. Invariably the sleightist would nod, or her eyes would light up and she’d excitedly move to rejoin the link, explaining West’s insight to the others as she did so. It was fine-tuning, but without West’s eye, these novel configurations wouldn’t blossom. They would startle, yes, so full of promise. But seeds—they would not, without him, become something beyond themselves. West was chef, gardener, alchemist. He would harvest.

Meanwhile, Monk’s director roamed at the level of the chambers, bumbling. And then suddenly, he’d needed to be gone. He told West, who told the troupes. There were familial matters, he’d be back before tour. Byrne thought, probably not. He might have felt sorry for the man. He didn’t. For one thing, Monk seemed more at ease; not everyone liked West, but they didn’t doubt him. Only Kitchen seemed sad. He sometimes ran rehearsal from his customary perch atop a stool in the corner. He liked a balconist’s perspective, he’d explained to Byrne—the cheaper seats. He mentioned Monk’s missing director whenever there was a question of line. The man had an eye, it couldn’t be denied, for the organics. How to prepare the shell for immolation. Lark noted none of the troupe politics, or didn’t care to speak of it. She rarely spoke at all—a little, if prompted, over late dinners. They ordered in, or she cooked, and at her suggestion he bought a case of wine. He liked vodka better, but drank as he was asked. She was a good, quick cook, and Byrne ate better than he could remember. She talked to Drew and Nene over the phone each evening, but about day-to-day stuff. Filler. Lark asked questions while stirring a white sauce or chopping scallions; she didn’t mention her own work. Byrne’s apartment was dim, and her forced cheer fluorescent. Of course she both loved and missed them, but the way the telephone coerced language was simply wrong. Byrne cringed at the bright, heavy assurances. Though it was done with rocks, not electric, not wireless, he was reminded of the medieval torture used on witches and during the Inquisition—called what? Pressing.

It didn’t surprise Byrne then, the way Lark worked alone in chamber four during the day. As if coming out from under something. She hadn’t yet the stamina of the rest of them, but she moved her sphinx-like musculature with vicious will. The other sleightists worked steadily for hours, repeating links eighty or ninety times before letting up, but Lark rarely repeated anything. She would go through a whole series of gestures with an architecture, twenty minutes worth, then hurl the thing across the room and fall to the floor, heaving. Byrne, the first few days, thought she was frustrated, that it had been too long since she’d been in a chamber. Soon, however, he realized what she was doing: not wicking. If she left her manipulations rough, threw down the architectures when she felt it coming on, she could keep from going out.

She worked that way, in fits, getting to know each of Clef’s seventeen architectures. Sometimes she’d go get Clef. They would bundle up—Lark in the parka Byrne had loaned her, Clef with her ridiculous scarf—and walk out into the bleak, perpetual threat of snow that hung over York. In the chambers, Lark kept mostly to herself. A few times she left to grab a sandwich or a second coffee with Yael and Manny, two sleightists she knew from before. And when she and Kitchen passed by one another, they exchanged a strained nod. Byrne was beginning to find Kitchen’s style of sleight irritatingly cerebral.

Lark had been up four nights in a row, sketching. It made Byrne’s sleep fitful, the light and the scratching sound from the living room/kitchen. His bedroom was small and at the back of the second-floor apartment he rented. He thought of blocking the large gap beneath the door with a pillow, but that would have impeded the heat from the one working radiator, the one that clanked and spat. Many tenants previous, that radiator had been painted, like the room, the color of clotted cream. Now, the paint was chipping in flakes so heavy they must contain lead. Still, the place had charm: a high ceiling with crown molding and French windows, and in the corner next to the fire escape—cobwebs, safely out of reach, alive in the rising heat.

Dirt was usually a comfort to Byrne; he’d been shocked when Drew and Lark’s house, in its cleanliness, had failed to make him uneasy. In fact, he’d admired how they combined a poverty of goods with deep care: dishes, mismatched but hand-washed and dried immediately following each meal; dustless, secondhand books; open windows and the freshly laundered, repurposed bedsheets that graced them. In his own apartment, Byrne had no broom nor any desire to knock the friendly wisps down, and he refused to spray. Oversanitation hid things more sinister than germs. Ammonia, turpentine, bleach, paint: chemicals made his eyes water, made his meager chest tense and knit together across the sternum.

After half an hour of covering and uncovering his head with a pillow, he walked out. Lark was sitting at the poker table where they ate, leaning into her paler left hand. Her right was held poised above the graph-paper notebook she’d bought on their way up from Georgia but had only begun using in the past few days. Her bluish hand swept back and forth above the windshield of blank page. Suddenly, she stabbed the grid. Then dropped the pencil and looked at Byrne.

“I have one. Inside of me right now.”

“What?” He thought he knew what she meant, but he hadn’t been prepared to hear it, and it sounded … mad.

“Since we saw the new links that first day. I’ve had a Need inside of me. But it’s different, it doesn’t know what it wants.”

“Lark, what are you talking about?”

She rifled one-handedly back through the notebook. She must have gone through twenty sheets, maybe more. Byrne was shocked to see so much work, all of it crawling with detail. Strings of ink not quite adhering to the pages.

“Look. Look here. She pointed to one. He moved closer, walked around to her side of the table. It was swingsets or seesaws, catapults or trebuchets. There was a transfer between the playground equipment and siege weaponry. This wasn’t ambiguity, like the drawings he knew from her book—it was actual movement. A trick picture, like the two silhouetted faces that became a goblet or vice versa, only it wasn’t about positive and negative space. He couldn’t control how he was seeing it, couldn’t force one image over to another. Each time the catapult shifted into seesaw, it shifted itself. And there was something else. On the way, the drawing passed through gallows. Byrne followed the lack: missing pitch, missing condemned, missing child. And back again, and repeat. Pitch, again. Child. Condemned, and … Repeat. It was chilling.

“I don’t. I don’t know what this is.”

“Here, look at this one.”

She was sweating, he noticed. There was an acrid smell; it was a caffeinated sweat. Her ring finger scratched rhythmically at her scalp. She had not raised herself from her slumped position, only pushed the book toward him and turned the page. There. An exhaustive analysis of a human eye was also a veined egg, swollen, with a tic in what was sometimes the cornea, sometimes not. Looking at the transmuting form, Byrne knew whatever was undeveloped, inside, would not have the strength to tear through. This depiction of unachieved birth was also a representation of vision. Byrne thought,

This is how she sees.

She closed the notebook. Byrne listed toward the fire escape for a hit of cold air and the vodka he kept there. He quickly let in then shut out the night—the palpitating bass from a passing Buick, a siren moving away. He walked over, put the vodka on the stove, and reached up to the cabinet above for two mugs. He poured them each a fair helping, four fingers. Lark was shoving the book into the duffel at her feet. “No,” he said. “No. I need to see them all.”

26

Each sleightist has a unique method of training, distilled from endless hours with multiple instructors. The classes taken prior to rehearsal and performance are, strictly speaking, not for the individual, but indispensable to forging a troupe identity. Without practice flocking and schooling, without a unified sense of what constitutes foray, absolution, swarm, and congress, the members of a troupe would be suspended and then dissolved. Prey in their own webs.