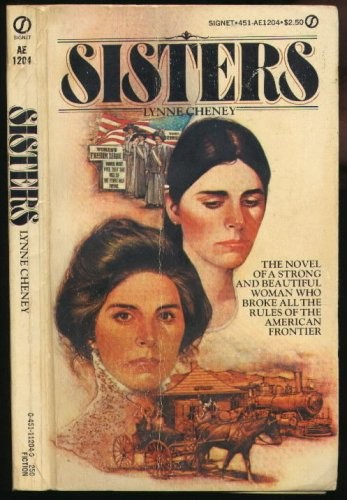

Sisters

Authors: Lynne Cheney

This is the transcription

of the Lynne Cheney Sisters blog, devoted to spreading the wonderful

book to all

those who want it, but cannot find it in any of the

used bookstores which were supported to meet their need for it.

Please, read on, as the book finally gets what it is due.

The

original transcription can be found at

http://www.livejournal.com/users/lynnecheney/

On every side, there was

emptiness. On every side, the prairie stretched on and on, unbroken

to the horizon. Even the dome of sky was a naked stretch, swept bare

of clouds by the unceasing wind. In all its vast blueness, the only

interruption was the inescapable sun. She felt its heat. She saw the

shadow it made, her shadow, a startling darkness in the bright and

infinite loneliness.

Sudden she knew she must

hurry. But which direction? Which way should she go? She scanned the

landscape, her head moving in nervous jerks, but there was no

indication, no hint at all, and she had to hurry! Panicky now, she

grabbed up her skirts and started running. Without plan or direction

she ran , the hard earth jarring her every step, the wind tearing at

her until her hair fell loose around her shoulders. She ran until her

breath came in deep rasping sobs, forever it seemed, but when she

stopped and looked around, she still saw the uninterrupted expanse of

prairie, and so she forced herself to run again.

She hadn’t pushed

herself like this since childhood, but she remembered the trick to

it. Her body screamed at her to stop, from a place somewhere in the

base of her skull, and once she identified where the screams were

coming from, she bundled a quivering mass of nerves and lifted them

to her forehead, to a spot above her eyes, where she could smile

disinterestedly at their violent protests and go on.

But it took such an

expenditure of will to keep the jangling mass suspended. She could

only do it so long before it began to break loose and invade every

part of the brain. Finally she knew it was too much. She continued to

run, but now she was courting exhaustion, hoping for oblivion. She

kept forcing herself to take one more step, then another, until at

last she fell, collapsing into a heap on the dry prairie floor. The

sun beat down on her. The wind whipped around her. She tried willing

herself into unconsciousness, but it was no use, and so with great

effort she drew her knees to her chest in a gesture of

self-protection. Would it never be over? Would this nightmare never

end?

Time passed. Seconds,

hours, perhaps even days. She didn’t know how long, and she

didn’t care. But gradually she became aware of a growing

quietness and coolness. She pulled herself to a sitting position and

found that somehow she had come into the shelter of a bluff. It

loomed hugely above her, an ancient hill, striated by winds, rid of

its gentle slopes, and pared to an inner core so that it rose

abruptly from the prairie. In its presence she felt protected,

soothed, comforted.

It wasn’t long before

she rose to walk closer, and as she approached, she saw that the face

of the bluff was less regular than she had first imagined. Partway

up, just slightly above her head, was a large cave. Where once there

had been a softness in the core of the hill, the elements had carved

an opening, and when she saw it, she knew this is what she had been

running toward. This is what she had sought—and been terrified

she might never find. Within the cave would be an embrace of peace

and protection. Everything would be taken care of once she was

inside, all pain relieved, all worry and fear turned aside. Although

she had never seen this place before, she knew that she was almost

home.

She reached up for the cave

the way a child reaches up to be lifted, and she was vaguely

surprised when no one bent down to help her. She began to struggle to

pull herself up, clawing for a fingerhold, straining her arms until

she felt the muscles start to cramp. And then, just when she thought

she couldn’t make it, she managed to get a leg over the lip of

the opening, and with a final, aching effort she was up, rolling into

the cave. She came to rest on a rocky floor, and in an ecstasy of

relief, gave herself over to the darkness.

But suddenly she knew she

wasn’t alone. No sight or sound told her, but she knew with

every atom of her being that someone or something was with her. The

knowledge immobilized her. She didn’t move. She scarcely

breathed. Not because she thought she could hide her presence. It was

too late for that. Whatever was in here had to know she was here too.

She didn’t even hope to be ignored; she was simply paralyzed by

the stunning realization that she was not alone, locked in an

unreasoning atavistic response.

Her heart pounded wildly.

In a moment, she dared move her eyes, and she let them follow the

floor of the cave to deeper within. Accustomed to darkness now, she

saw the body. Even as the paralysis broke and she scrambled toward

it, she knew who it was—what it was. Helen. She looked down at

the broken figure on the cave floor and saw her sister, Helen.

Horror engulfed her,

counterpointed instantly by a paroxysm of terror running up her

forearms like an electric current, seizing the muscles of her neck,

forcing her head up to what she already knew was there. Gleaming

animal eyes. Black lip curled back to reveal white fang. Carcajou!

Carcajou! Spawn of the devil. Destroyer of life. The animal screamed,

and she called out its name: Carcajoooouuu!

*

Her eyes snapped open, wide

open, the pupils too dilated to focus at first.

“Mrs. Dymond, are you

all right?”

She took a moment to

answer, a moment trying to shake off the nightmare.

“Mrs. Dymond? Ma’am?”

“Yes, Connie, yes,

I’m fine. I was just dozing.” But her heart was racing.

She focused on the sound of the moving train, trying to calm herself

with its rhythm. “Is it far now?”

The maid shook her head.

“Not far, ma’am.”

She stood, steadying

herself against the train’s sway with on the back of the plush

settee. She started toward the rear of the private car, but the maid,

who chose that moment to step forward with a clothes broom, bumped

into her. The clothes brush clattered to the floor.

“Oh, ma’am,

excuse me--it’s the dust and cinders.” Connie fluttered a

hand toward the ashy speckles on her employer’s navy-blue

skirt, then got down on her knees and groped under the settee for the

clothes broom. “It was so hot, I opened the windows, and

everything started blowin’ in.”

“In a minute, Connie.

I’ll be back in a minute.” She walked to the rear of the

private car and entered the mahogany-paneled dressing room with its

white marble fixtures and green velvet draperies. Twisting an ornate

tap, she rinsed her hands, then dampened a fresh linen towel and

dabbed at her face. It helped her feel less hot and grimy, though it

did nothing to dispel the slight nausea which comes with so many days

on the train. Nor did it remedy the nightmare’s lingering

horror.

Quickly she shifted her

thoughts. This was her third journey by train from New York to

Wyoming. The first had been in 1874, twelve years ago now. Rail

travel had become easier in the time since, but only because it was

over sooner. Trains might be faster now, but they were as hot, dirty,

and noisy as ever. She ran more water on the linen towel, wrung it

out, and held it over her face. Then she discarded the towel and

massaged the back of her neck until the tight muscles began to

loosen.

By the time she had put

fresh scent at her wrists, she was cheered a little. A nice bath

could be dangerous, she thought, turning to look in the mirror. It

might make her so recklessly good-humored she’d consider

another long trip by train soon. She brushed at her skirt, adjusted

the sash, and then moved close to the mirror to put on her hat. As

she studied the image in the glass, an unexpected thought brought a

wry smile. That face--she’s seen it pictured so many times, it

seemed incomplete without a caption. The label was missing, the

tagline calling her “a beauty of the day” or some such

gush. And where was the inevitable second line? The one set in

smaller type that portentously declared: “Sophie Dymond

commands publishing empire founded by her late husband, Philip.”

Her appearance and her

position were always mentioned together, and she suspected it was no

accident. If she was considered beautiful, it was probably because

the editor of Dymond’s Ladies’ Magazine ought to be.

Certainly the face looking out from the mirror was unusual, striking

even, but it had none of the round and rosewater kind of prettiness

currently in favor. Judged by those standards, her mouth was too

wide, her cheekbones too high and flat, her complexion entirely too

dark. And her heavy black hair wouldn’t hold the curly fringe

fashion demanded. Instead it was all long and loosely waved, drawn

back and knotted low on the neck.

With a fingertip she

smoothed at the tiny lines radiating from the outer corners of her

eyes. Was it age that was troubling her? Though few people guessed

it, she was only a few years from her fortieth birthday. Could

growing older account for nightmares of death and dying? She let her

hand fall, thinking it was less age than circumstance. She was going

to Cheyenne to see her grandfather, Joe Martin, who was dying after a

stroke. Three years ago, her husband had died of cancer. Not even a

year ago, her sister… Her mind tried to skitter away from the

thought of Helen because it threatened to call up the dream. But why

Helen? Why was her death the one that troubled above all? When she

had learned Helen had died, she had been plagued for months by an

unreasoning terror she would encounter her corpse somewhere. It made

no sense at all. She was in New York. Helen died in Wyoming. And yet

she was possessed by a fear of finding her body lying in the entryway

of her brownstone in New York or thrown on the floor of her office,

its limbs at odd angles, like a huge discarded doll’s.

She shook her head and

forced herself to the task of pinning her hat. Was it the way Helen

had died? No, it was guilt troubling her more likely, regret for not

knowing her sister better. For not liking her more, to be honest.

Quiet, proper Helen; her careful ways had always seemed a reproach.

Her caution had stirred an antagonism which Sophie had to admit she’d

done little to still.

And the way Helen had died

was probably far less important than the fact she’d been just a

year younger than Sophie. The frights and dreams were probably fears

natural to having a sibling who was such a close contemporary die.

Probably it had made her afraid of dying herself, she thought,

holding the eyes of her mirror image for a moment before she turned

away.

Back in the observation

room, she picked up Tom, her black-and white Pekingese, from the

basket where he was sleeping and then sat down, letting him arrange

himself on her lap. She stroked him absentmindedly and looked out at

the prairie. She could see so far, it reminded her of crossing the

ocean. “An inland sea,” she murmured. “It’s

like a great brown sea.”

“Oh, ma’am,

that’s true. I never knew there was anything like it!”

Sophie looked at the girl

in surprise. Hardly aware she’d spoken aloud, she hadn’t

meant to start a conversation.

The girl hurried on, her

eyes wide. “I mean, you keep expecting something different, but

it goes on forever, and it’s all the same!” She was very

earnest and very young, and though she meant well, still her

breathless assessment grated a little.

“Not really, Connie.

Not when you look closely. It just seems the way to you because it’s

different from what you’re used to.” Sophie turned away,

looking out the window again, and she saw a line of cattle walking

along the edge of a dry creek bed. Ridiculous creatures, she thought.

Just like human beings, the way they can move so purposelessly along

without the slightest notion of a destination. And then the cattle

disappeared into a draw, and she saw a flash of the dream. She saw

herself running, running.

Quickly she looked away

from the window. “You know, Connie, when my sister and I were

small, we used to watch the wagon trains coming into Fort Martin, and

the people in them always looked bewildered. We thought it was

because they were tired and had come so far. But I wonder if it

wasn’t the prairie. I wonder if they weren’t dazed by the

openness of it.”

“I know I sure miss

the trees, ma’am.”

Sophie had been talking to

distract herself, not really expecting the girl to understand, but

when Connie caught some of her meaning, she went on, “I

remember when I first went East, the trees nearly drove me mad. I

couldn’t stand so many things growing everywhere. I felt as

though I couldn’t breathe and couldn’t see.”