Sir Francis Walsingham (35 page)

Read Sir Francis Walsingham Online

Authors: Derek Wilson

Walsingham was too honest to condone by his silence Elizabeth’s subterfuge and too canny to shoulder the blame for her actions.

What I believe happened was something like this: the previous December there had been a falling-out between the queen and her secretary which had resulted in the latter leaving the court. He had subsequently been taken ill and was completely incapacitated throughout most of January. By the end of the month he was sufficiently recovered to return to his house in the City and to conduct business from his sickbed. It now suited Elizabeth to keep him away from the centre of the action, even though vitally important matters of state were cropping up thick and fast. The business of the warrant would never have worked if Walsingham had been the courier. Therefore, she deliberately delayed his recall until mid-February. If anyone contrived Walsingham’s absence during the crucial days covering the end of the Mary Stuart affair it was the queen.

If Elizabeth had any doubts whatsoever about the priceless value of Walsingham’s service she had only to peruse the letter he wrote to John Maitland, his opposite number in Scotland, within days of his return to court. Reactions to Elizabeth’s execution of a foreign royal personage had been predictably harsh. Her brother monarchs in France and Spain were genuinely shocked and outraged by the deed, as were many of their Catholic subjects. Reports poured into Walsingham’s office of formal diplomatic protests and popular demands for revenge. On the quayside at Rouen mobs attacked English ships and their crews. From Paris Stafford sent so many accounts of French outrage that Walsingham abruptly told him to stop providing information that was upsetting their mistress. But the country most closely affected by Mary’s death was, of course, Scotland. On 14

February, Elizabeth had sent Sir Robert Carey to Edinburgh with instructions to give James the official version of his mother’s death. In a personal note she wrote of ‘the extreme dolour that overwhelms my mind for that miserable

accident’

(my emphasis). She proclaimed her innocence and assured the king: ‘I am not so base-minded that fear of any living creature or prince should make me afraid to do that were just or, done, to deny the same . . . as I know this [the execution] was deserved, yet if I had meant it I would never lay it on other’s shoulders.’

6

Well might we conclude, ‘The lady doth protest too much!’ The letter was not delivered. Carey arrived at the border to find it closed and all communication between the two nations at a standstill.

The execution of Mary had been a severe affront to Scottish national pride and popular demonstrations demanded reprisals. At court James’ nobles were urging him not to submit, in cowardly fashion, to this blow against his dignity. One courtier appeared before the king in fall armour, claiming that this was the only suitable mourning to wear for the ex-queen mother. More seriously, the French ambassador pounced upon the death at Fotheringhay as a means of turning James’ affections away from England and back to the ‘auld alliance’. It was to stiffen the young king’s resistance to any such blandishments that Walsingham wrote his long letter, fully intending it to be brought to James’ attention. Could he succeed where the queen had failed?

Walsingham wasted no ink justifying what had been done. His letter was couched purely in terms

of realpolitik,

with a large element of bluff. He advised the king not to allow himself to be drawn into a warlike alliance against England, a nation which was ‘so prepared . . . to defend itself, both otherwise and by the conjunction of Holland and Zeeland’s forces by sea’ that it ‘need not fear what all the potentates of Europe, being banded together against us can do’. Walsingham preyed upon James’ known dislike of violence by suggesting that any war might result in the king being taken prisoner or slain. France, he warned, was only interested in restoring Catholicism in Scotland. And let not James, Walsingham lectured, delude himself into thinking that he could ride the tiger of Spanish militarism

and avoid the inevitable consequences. Philip would be no more disposed than Henry III to permit the union of England and Scotland, nor would he allow James to exercise his own religion.

Should he seek to placate the powerful continental monarchs by voluntarily converting to Catholicism, this would not save him. He should contemplate the fate of Dom Antonio, a devout Catholic prince despoiled of his inheritance by his voracious neighbour. Finally, Walsingham pointed out that espousing the Roman faith would not win him support south of the border. English Catholics, he averred (presumably with tongue in cheek) were all united in their loyalty to the Crown. English people would not welcome him: ‘the Protestants because he had renounced the religion wherein he was with great care brought up, the papists because they could not be assured in short space he was truly turned to their faith. Yea, all men should have reason to forsake him who had thus dissembled and forsaken his God.’

7

This letter certainly struck the right note insofar as James VI was very carefully weighing his options. If he bided his time and meekly took his pension then the chances were that the ripe fruit of the English Crown would eventually fall into his lap. On the other hand, with foreign help he might harvest that Crown much sooner. Walsingham tried to persuade Elizabeth formally to acknowledge James as her heir but she was as immovable as ever on that subject. However, James was, very slowly, brought to regard discretion as the better part of valour and to resist the sabre-rattling of his more belligerent nobles.

Scotland was only one of Walsingham’s worries. He was still busy keeping the Low Countries war going and trying to persuade Elizabeth to succour the Huguenot cause. He was even trying to persuade the Ottoman sultan to renew anti-Spanish hostilities in the Mediterranean. As he confessed to a friend: ‘I had never more business lying on my hands sithence I entered this charge, than at present.’

8

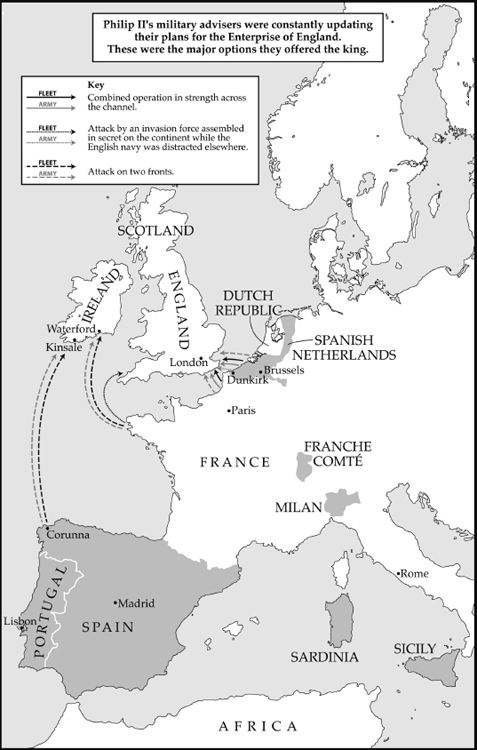

But the great challenge was preparation for Philip’s Armada. Walsingham forced his ailing body to keep going long enough to cope with that crisis he had always known as inevitable. The coming together of Catholic forces against England which he had feared was now a reality. Everyone knew that Spain’s long-mooted invasion was

imminent. But there was no agreement as to what Philip’s strategy was, how large his fleet would be, when or at what precise target it would be launched. Never was intelligence work more important than in these nail-biting months and Walsingham’s expenditure on his network increased dramatically. Accurate figures are impossible to achieve but we shall not be far out if we reckon that in 1587–8 Walsingham spent half as much again as in the previous year. He reorganized the system. A ‘Plot for intelligence out of Spain’, drawn up in spring 1587, made provision for the setting up of a clearing house in Rouen to handle information gathered by agents in France’s Atlantic ports and for staff in other agencies to be increased. One reason for this reconstruction was that in 1585 Philip had closed all Spanish ports to English merchants. Intriguingly, Italy was the most vital intelligence nerve centre for keeping up to date on Spanish activities. All the independent states in the peninsula maintained their own embassies in Spain and were often the first to discern significant movements of ships and men. They were usually quite obliging about selling on information to England. Walsingham’s couriers were constantly toing and froing along the roads between Italy and the Channel coast.

A glut of information can be just as dangerous as a dearth. The true art lies in properly evaluating it. Throughout the summer his staff tried to decipher and co-ordinate reports that simply could not be squared. In July, fifty-seven ships and 10,000 troops were supposedly assembled in Lisbon and only waiting to link up with the convoy vessels from the silver fleet. But another report gave the numbers as a hundred ships and 15,000 soldiers. By mid-September the Armada had, reputedly, set sail – en route for a landing in Scotland. These alarmist messages were all false. Any estimate of Spain’s preparedness for the Enterprise of England was complicated by many factors. Philip kept changing his plans. He received conflicting advice from Parma and from his chief naval adviser, the Marquis of Santa Cruz. Negotiations with Sixtus V went unsatisfactorily because the pope was reluctant to make the degree of financial commitment the king looked for. When Philip did begin to assemble his fleet annoying attacks by Francis Drake obliged him to modify his plans. Another problem Walsingham had to contend with was the deliberate misinformation coming from Stafford in Paris. The ambassador fed the English government with stories provided by Mendoza: Philip’s intentions were entirely pacific; Elizabeth had more to fear from France than from Spain. He even tried to make the queen believe, in January 1588, that Philip had disbanded his fleet. This was a particularly reckless ploy to try, flying as it did in the face of all the evidence Walsingham had to the contrary. It also created family tensions. The brother of Stafford’s wife was Lord Admiral Howard, the man whose secrets Stafford was betraying. Howard’s embarrassment was acute, as he told Walsingham: ‘I cannot tell what to think of my brother [-in-law] Stafford’s advertisement; for if it be true that the King of Spain’s forces be dissolved, I would not wish the Queen’s Majesty to be at this charge that she is at; but if it be a device, knowing that a little thing makes us too careless, then I know not what may come of it.’

9

There was a certain subtlety to Stafford’s ‘device’ because it told the queen what she wanted to hear. Keeping ships and men in readiness to face invasion was an expensive business. Throughout 1587 Howard, backed by Walsingham and the other hawks, had to fight for every penny the navy needed. At the same time the doves, headed by Sir James Croft, were in communication with Parma about the possibility of English withdrawal from the Low Countries. Philip’s governor was only stringing England’s envoys along but Elizabeth persisted in believing that all-out war with Spain could be avoided.

To hold the queen to a firm stance Walsingham needed every scrap of reliable intelligence he could lay hands on. Fortunately the network he had painstakingly built up over the years was equal to the challenge. His best placed agent was another of those adventurous Catholic exiles for whom personal survival counted more than religious zeal. Anthony Standen had been a member of Mary Stuart’s household before 1568. After Mary’s escape from Scotland, Standen, who was currently in France, considered himself an agent for his former mistress, while also establishing contact with Walsingham. After sundry adventures he fetched up in the household of the Medici Duke of Tuscany. Standen cultivated many Spanish contacts but his

most useful were the Tuscan ambassador to Spain who passed on information from Philip’s court and a certain Fleming who was a close attendant on the Marquis of Santa Cruz, the Spanish Grand Admiral. Thanks to Standen, Walsingham received intermittent reports of the extent and disposition of Philip’s ships and men and the evolution of the king’s plans. He was able to conclude that the Armada would not sail in 1587 but that all efforts were being directed towards an invasion in the following year. The political plan, as it emerged after the death of Mary Stuart, was that Philip’s daughter, Isabella, would be proclaimed queen after she had been suitably married off to one of her Habsburg cousins. The interim government would be placed in the hands of none other than Dr William Allen who would oversee the restoration of Catholicism and the confiscation of every acre of church land seized by Henry VIII half a century earlier. It is as well for the modern reader to be aware of the chaos and inevitable bloodshed which would have resulted from a successful invasion in 1588. Standen, who rapidly proved his value, was generously pensioned by Elizabeth in 1588, when he travelled to Madrid and reported directly from the enemy camp.

From various sources Walsingham learned of the impact of Francis Drake’s raid on Cadiz. This was an enterprise either conceived or encouraged by Walsingham and Leicester. As soon as Walsingham was back at court, and while Burghley remained under a cloud, Elizabeth was persuaded to authorize a strike which might inhibit Philip’s preparations. A purely private scheme originated by some London merchants to make a piratical attack on Spanish vessels to recoup losses they had sustained as a result of Philip’s trade embargo was taken over by the government. Seven naval vessels were added to the fleet and Drake was put in charge of the operation. This was in mid-March. Now preparations had to be completed at speed before the queen experienced one of her changes of mind. Drake and his ships got away from Plymouth on 2 April. A week later a fast pinnace was despatched severely restricting Drake’s orders. The queen demanded that he should only apprehend enemy vessels on the high seas and not enter any of Philip’s harbours. ‘Unfortunately’ the pursuing ship encountered contrary winds and was obliged to turn back, the

message undelivered. The result was the celebrated ‘singeing of the King of Spain’s beard’, the devastation of Cadiz harbour, the destruction of some two dozen ships and the capture of four vessels which Drake loaded with loot, including supplies which had been intended for the Enterprise of England. In terms of military advantage the Cadiz raid achieved little. The loss of a few ships was unlikely to deter Philip from his grand project. But the audacious attack did further unhinge Philip’s plans. It deterred several captains, en route from the Mediterranean to rendezvous with the Armada, from venturing into the Atlantic and it demonstrated the vulnerability of galleys to English vessels with superior fire power. Santa Cruz’s plan had relied heavily on the use of galleys to move well inshore and take on board many of the troops Parma was to assemble on the Channel coast. This scheme was now drastically revised.