Sir Francis Walsingham (2 page)

Read Sir Francis Walsingham Online

Authors: Derek Wilson

This fundamental clash of opinions created intense frustration and tension between the queen and her secretary of state. She found his plain speaking at time offensive and he was frequently driven to distraction by her moral squirming. It is surprising that they could work together at all. Yet work together they did through this time of national testing. Therefore exploring their extraordinary relationship illuminates for us what was at stake in these years. Generations of biographers and historians have sought to explain what made Elizabeth tick. It is high time we explored the motivation of Francis Walsingham.

AUGUST 1572, DEATH IN PARIS

They cut down Mathurin Lussault on his own doorstep. The householder answered an insistent knocking and when he opened the door a neighbour, screaming obscenities, ran him through. His son rushed downstairs to see what the fracas was about. He was grabbed and stabbed several times. He staggered into the street, where he died. Mathurin’s wife, Françoise, threw herself from an upstairs window in a bid to escape the assassins. She broke both her legs in the fall. Friends tried to hide her but, by now, the mob’s blood was up. They were forcing their way into homes in their search for more victims. Finding Françoise, they dragged her through the streets by her hair. They cut off her hands in order to get her gold bracelets. What was left of the poor woman was impaled on a spit and paraded through the streets of Paris as a gory trophy, before being dumped in the Seine which was already streaked with red.

On the streets panic reigned. Church bells were ringing. Shots were being fired. As the carnage intensified the air filled with more human sounds – shouts of triumph, religious slogans, screams of fear. The English ambassador to the court of Charles IX threw open his casement in the usually quiet Faubourg St Germain to see what the commotion was about. He was not left long in doubt. Terrified men and women came battering on his door begging for asylum. When the servants let them in they babbled out their tales of barbarism and inhumanity. Tales the like of which the forty-year-old Francis Walsingham had never heard before. As the day wore on more and more fugitives packed into the house. Then soldiers arrived –

royal soldiers – demanding that the enemies of the state be handed over. Francis, though fearful for the life of himself and his family, stood firm. He was able to save the foreign nationals sheltering beneath his roof but the few French Protestants who had sought shelter there he was forced to surrender. They joined the toll of more than 2,000 men, women and children massacred in Paris on St Bartholomew’s Day – not far short of the number who perished there during the Terror of 1793–4.

This traumatic experience had a formative impact on Queen Elizabeth’s ambassador. He was disgusted by the behaviour of the mob, indignant at the implication of the king and his mother in the atrocity and appalled at his own powerlessness to help the afflicted. These tragic events undergirded his political convictions thereafter and the advice he gave his sovereign. But they did not change his fundamental beliefs that Rome was the whore of Babylon and Catholics the very limbs of Satan. One thing he knew with an unshakable certainty: the religion responsible for such ghastly atrocities must never ever, under any circumstances whatsoever, be allowed to re-establish itself in England.

BACKGROUND AND BEGINNINGS

1532–53

There is a sense that tombs and graves bring us close to the departed. It is understandable that people should think of memorials as material conduits to their deceased loved ones. It is perhaps less intelligible for historians to seek contact with their subjects by visiting their final resting places. Fortunately, no such temptation besets the biographer of Sir Francis Walsingham. In 1590 his remains were quietly and honourably interred in St Paul’s Cathedral. His memorial, along with scores of others, vanished without trace in the fire of 1666 and the subsequent buliding of Sir Christopher Wren’s basilica. Interestingly, a similar fate befell the tombs of Francis’ parents. William and Joyce Walsingham were members of the congregation of St Mary Aldermanbury, close by the Guildhall, and were, presumably, interred there. Like the cathedral, St Mary’s suffered in the Great Fire of London. Also like St Paul’s it was rebuilt in Wren’s neoclassical style. Sadly, its afflictions were not over. The Blitz of 1940–1 destroyed the new church. After the war it

was

rebuilt – but not

in situ

. A strange fate awaited it. Its stones were meticulously numbered and shipped across the Atlantic to Fulton, Missouri, where they were reassembled on the campus of Westminster College as a memorial to Sir Winston Churchill.

So we can make no physical contact with Elizabeth’s minister or his immediate antecedents. In a way it is fitting that this should be so. It adds something to the mystique of a man who was self-effacing in his lifetime and who has remained something of an enigma ever since. Walsingham was that rarity among members of the Tudor establishment –

a man who reached the political heights not by greasing palms, elbowing aside rivals and flattering his sovereign and her close attendants, but by talent, industry and the honest application of his principles. It is largely for this reason that a gauze screen of vagueness obscures his early career. There is no trail of correspondence with the rich and powerful such as an ambitious man might leave. There are few references in his later writings to his parentage and the self-conscious steps by which he reached the summit of Elizabeth’s government. Diligent search among local archives has disclosed all that is known and probably all that ever will be known about Sir Francis’ origins.

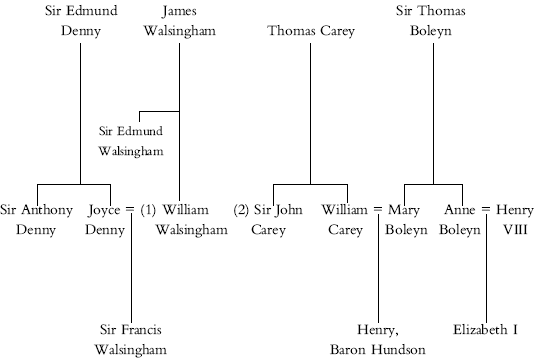

However, there is a line of approach which enables us to augment the bare catalogue of land transactions and wills. Walsingham was a man of his time. Indeed, his life is incomprehensible without a consideration of the momentous events which occurred throughout six decades of religious, political and social revolution. This was an age in which prominent men had to take sides, to declare themselves for the old faith (Catholicism) or the new (Protestantism or, more accurately, evangelicalism). The motives for such a declaration might be religious conviction, self-advancement or a combination of the two and there were always those who skilfully mastered a Vicar of Bray-style flexibility. Nevertheless, we can deduce much about mid-Tudor men and women by the company they kept and the familial alliances they made. The Walsingham genealogical tree is, therefore, informative.

The Walsinghams of the fifteenth century (which is as far back as we need to go) were in trade but already upwardly mobile. Francis’ great-great-grandfather was a shoemaker and his great-grandfather a vintner. Both were honoured men in their professions, prominent members of their respective guilds and well known in London society. They had accumulated property in the capital and – a mark of true gentility – owned a modest country place in Kent (Scadbury Manor, Chislehurst). From this solid base the next generation took a further significant step up the social ladder. James Walsingham was put to the law and, by the time Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond, grabbed the Crown in 1485, he was well established in the London

courts. It could not have been a more propitious time for following a legal career.

The English had (and still have) an ambivalent attitude towards lawyers. They were seen as men who could manipulate ancient statutes to their own advantage, who favoured the rich against the poor and were not averse to taking bribes. At the same time, anyone seeking justice had to employ the experts and by 1500 more than 3,000 new suits per annum were being presented in the courts of the capital alone. The law was a hard trade to master but a lucrative one to follow. More importantly, it was becoming a stepping-stone to that place where

real

fortunes were to be made – the royal court. For half a century the fate of rival royal dynasties had been decided by baronial armies. The new king decided that the weight of his regime would be borne not by steel blades but by paper statutes. He would employ the nation’s best legal brains to strengthen his position and secure the succession for his heirs. Over the ensuing decades the balance of the royal Council changed; the barons and senior ecclesiastics who had assumed that they were indispensable to the government of the country had to make room for new men, versed in the law and loyal only to the Crown.

James Walsingham, Francis’ grandfather, never made it to the very top of the tree – membership of the royal Council – but he was one of the leaders of royal society: a justice of the peace, member of various royal commissions and Sheriff of Kent in 1486–7. He consolidated his position in the county and acquired a grant of arms from the College of Heralds. And he ensured that his two sons would be drawn to the attention of the king. When he died, full of years, in 1540 he had cause for satisfaction that his family had received significent marks of royal favour. He could not, however, have foreseen that his youngest grandson, Francis, was destined to become one of the nation’s leaders. His greater expectations were focused on the career of his son and heir, Edmund.

The young extrovert prince who came to the throne in 1509 as Henry VIII sought his companions among macho, athletic, patriotic Englishmen like himself. It was no coincidence, therefore, that Edmund received a martial training. In 1513 he gathered some retainers about him and joined the 20,000-strong force being hurriedly assembled on the northern border by the Earl of Surrey to ward off a Scottish invasion. The ensuing victory at Flodden was one of the most bloody and decisive ever achieved in the long history of Anglo-Scottish warfare. Several captains were afterwards knighted by Surrey – among them Edmund Walsingham. The young man’s exploits were brought to the attention of the king and Edmund’s place among the young blades of the court was secured. He appeared frequently in the tiltyard as an accomplished horseman and exponent of sixteenth-century martial arts. In 1520 he was chosen as one of the knights to accompany the king to France for the sumptuous diplomatic display which has gone down in history as the Field of Cloth of Gold. It was a signal sign of Henry’s confidence in Edmund that, in 1521, he gave him charge of England’s major fortress-prison, the Tower of London. The man responsible for the Tower was the Constable and, for most of this period, that was Sir William Kingston, but it was the Lieutenant who actually resided there and was responsible for day-to-day administration.

Sir Edmund Walsingham was destined to be Lieutenant of the Tower during its most bloody and controversial years. Henry VIII

ruthlessly used the grim stronghold for cowing opposition to his policies, disposing of possible Yorkist rivals and for applying the ‘final solution’ to some of his marital entanglements. Among the notable prisoners incarcerated there and executed within the walls or on the adjacent hillside were Thomas More, Bishop John Fisher, Queen Anne Boleyn, Queen Catherine Howard, the Marquess of Exeter, the Countess of Salisbury, Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. There were many more smaller fry who faced torture, deprivation and the axe in Henry’s police state.

Edmund Walsingham proved himself to be the ideal jailer and guardian of the Tower’s grisly secrets. He carried out his duties without flinching and was ever determined to demonstrate his unreserved loyalty. In reality, he could do no other. The men and women entrusted to his care had incurred the royal displeasure. To show sympathy for them would be to run the risk of arousing Henry’s mercurial ire. He might – and did – lament to Sir Thomas More that he was unable to make his quarters more comfortable but, as he explained, ‘Orders is orders’. We can gauge something of Sir Edmund’s temperament from the case of John Bawde. Bawde was one of the lieutenant’s own servants. He fell under the spell of Alice Tankerville, a prisoner in Coldharbour within the Tower of London. So besotted was he that he tried to help her to escape. The bid failed and his complicity was revealed. Sir Edmund’s rage (doubtless fuelled by fear for his own position) was boundless. He had Bawde thrown into Little Ease, the Tower’s most notoriously vile cell. The prisoner was subsequently racked, condemned in a speedy trial and hanged in chains.

While Sir Edmund was leading an eventful life at the centre of power, his younger brother, William, was being groomed to take over the family responsibilities in Kent. He followed his father’s profession, held senior positions in London’s legal establishment and was prominent in the affairs of his shire. He steadily added other lands to the family’s holdings and, by 1530, was well established as a substantial gentleman with court connections. But William’s fortunes were mixed and his aspirations far from being smoothly accomplished. He married, sometime in the early 1520s, Joyce Denny, daughter of

Sir Edmund Denny, a minor courtier on the staff of the Exchequer. Perhaps the introduction to a court colleague was effected by William’s brother. The union, moderately important at the time, was to prove extremely influential in the later years of Henry’s reign. Joyce’s brother, Anthony, was another of that small army of hopefuls seeking preferment at court. He was fortunate in finding a short cut to royal favour. There were scores of men who held posts in the innermost chambers of the court but few of them could count themselves as the king’s friends. One of the privileged band of intimates was Sir Francis Bryan, soldier, diplomat and tiltyard companion of the king. Bryan was a gentleman of the privy chamber and trusted by Henry with delicate diplomatic missions, including an embassy to Rome in connection with his intended divorce from Catherine of Aragon. Anthony Denny, William Walsingham’s brother-in-law, was a member of Bryan’s entourage and his patron ensured his steady, but unspectacular, promotion. By the mid-1530s Denny was a groom of the chamber, one of those who attended the king most intimately. He was an educated, cultured man of pleasing disposition and Henry increasingly warmed to him.