Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir (24 page)

Read Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir Online

Authors: Linda Ronstadt

I closed up my New York apartment, put it on the market, and returned to the West Coast. The idea of a Mexican record was fully present in my dreams at night. The dream world of sleep and the dream world of music are not far apart. I often catch glimpses of one as I pass through a door to the other, like encountering a neighbor in the hallway going into the apartment next to one’s own. In the recording studio, I would often lie down to nap and wake up with harmony parts fully formed in my mind, ready to be recorded. I think of music as dreaming in sound.

18

Canciones de Mi Padre

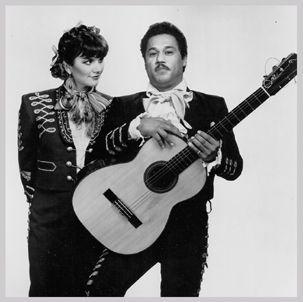

Photo by Robert Blakeman.

With actor and singer Daniel Valdez, who performed with us in the Canciones de Mi Padre tour.

T

IME SPENT WITH

P

ETE

Hamill had fortified my Mexican dreams. He had gone to school in Mexico City and had an unusual understanding of the sophisticated complexities of the Mexican art world, with a comprehensive grasp of Mexican literature, poetry, music, and visual art. The Mexicans have a fervent appreciation of poetry and make regular use of it. It occupies a high and ancient seat in the Mexican culture. The Aztecs called it “a scattering of jades,” jade being what they valued most, far more than the gold for which they were murdered in great numbers by invading Spaniards. They felt that the more profound aspects

of certain concepts, whether emotional, philosophical, political, or artistic, could be expressed only in poetry.

Mexican song lyrics, from sophisticated city cultures to the most basic rural settlements, are rich in poetic imagery. I was beginning to learn the words to the songs I had cherished since childhood and writing the English translations above the Spanish, so that I would know exactly what each word meant and be able to give it the proper emotional emphasis.

I was still casting about for someone to start teaching me the rhythmic intricacies of the songs, particularly the formidable huapangos, when I got another call from my father saying that the Tucson International Mariachi Conference had invited me to sing a few songs in its gala. The organizers were offering the famed Mariachi Vargas de Tecalitlán to accompany me, with its director, Rubén Fuentes, to write my arrangements. I was astonished! If I were singing standards, it would be like having Nelson Riddle and a full orchestra fall in my lap.

Mariachi Vargas is a band that formed in Mexico before the turn of the twentieth century and is widely considered the best mariachi in the world. Rubén Fuentes is a preeminent figure in the Mexican music business. He is a composer of many hits, and was the musical director of RCA Records in Mexico for at least a decade, producing a large number of ranchera recording artists, including Lola Beltrán. He was partners with Silvestre Vargas, son of the original leader of the Mariachi Vargas, and has produced and arranged for the band since the 1950s.

This was a tremendous opportunity, and I decided that I would try to learn three songs and figure out a way I could rehearse them before I had to go to Tucson and perform. I chose songs I knew from recordings that my father had brought from Mexico when I was about ten. I had heard them a lot but never attempted to sing them.

Rubén Fuentes flew to Los Angeles from his home in Mexico City to meet with me about the arrangements. My Spanish speaking ability is limited to the present tense, and my vocabulary is like a child’s, so I begged my dear friend Patricia Casado, whose family owns Lucy’s El Adobe Cafe in Hollywood, to come translate for me.

In addition to serving the best Mexican food in L.A., Patricia and her parents, Lucy and Frank, were like family to me. They were the same for any number of young musical hopefuls who recorded in the studios near their Hollywood restaurant, including the Eagles, Jackson and John David, Jimmy Webb, and Warren Zevon. We all relied on Lucy for great food and an encouraging word. She was known to tear up a check if she knew that a regular was having a bad stretch. The local police and firemen ate there, and received special consideration from Lucy, as did many journalists and politicians, including Jerry Brown, whom I met there when he was California’s secretary of state. Movie industry people from the Paramount Studios across the street came too, for both the food and the camaraderie.

When I returned home from a tour, I stopped there on my way from the airport. It was my home base.

A few days before Rubén arrived in L.A., I was lifting a heavy suitcase from the baggage carousel in the airport and injured my back. I could barely walk and had to stay in bed. To cancel the meeting was out of the question, as Rubén had come a long way, with the sole purpose of meeting with me. Patricia helped me tidy my hair and find a suitable dressing gown. She helped me hobble from my bed to the pink sofa in my bedroom, and we had our meeting there. I was embarrassed to be receiving him in such a state, but there was no other choice.

He arrived with Nati Cano, who was the leader of Mariachi Los Camperos, a band closely matched to Mariachi Vargas

in quality and based in Los Angeles. Rubén was in his sixties, handsome, urbane, low key, and I could tell that he was used to being in charge. Nati Cano, himself a brilliant musician and composer, would become my teacher and revered mentor for many years to come.

I showed Rubén the list of the three songs I had chosen. Two were huapangos, which, in addition to the complicated rhythm structure, require a lot of falsetto. He was surprised by my choices. “These are very old and very traditional,” he said. “How did you hear them?” I told him I had heard them since childhood. “They are difficult to sing. Maybe you should pick something else.” I wanted to sing the ones I had. He agreed to send the arrangements to Nati Cano, who assured me that I would be able to rehearse with the Camperos a few times before going to Tucson.

Nati Cano owned a downtown L.A. restaurant, La Fonda, where the Camperos appeared nightly. We rehearsed there in the afternoon, and I stayed to hear the show in the evening. In addition to the band, which featured one superlative singer after another, a pair of folkloric dancers performed traditional dances—“La Bamba” and “Jarabe Tapatio” being the outstanding numbers. I was much impressed by a particularly graceful young dancer, Elsa Estrada. Irresistibly charming in her beautiful white lace dress from Veracruz, she flashed her huge black eyes, heels drumming the intricate steps of “La Bamba”: “

Para bailar La Bamba, se necesita una poca de gracia

.” (To dance La Bamba, what is needed is a little bit of grace.)

Elsa had a bounty of grace. I decided that I wanted to put together a show in which I sang entirely in Spanish, featuring Elsa’s beautiful dancing. I wanted it to be based on little vignettes of different regions in Mexico, much like my Aunt Luisa had done with her presentation of folkloric songs and dances from Spain.

The performance I did of the three songs I had chosen to perform in Tucson was rocky, but unlike my experience in

Bohème

, I

felt that mastering the form was within my reach, and would simply be a matter of time and rehearsal. I found a teacher to show me the dance steps to some of the songs, so that I would be able to break down the rhythms and understand the phrasing better.

I asked Rubén if he would be interested in producing a record for me with the Mariachi Vargas, and he agreed to do it. Remembering my unhappy experience with Jerry Wexler, I decided to hedge my bet and include Peter Asher as coproducer.

When my record company heard my new plans, the people there were certain I had finally lost my mind: Record archaic songs from the ranches of Mexico? And all in Spanish? Impossible! I pleaded with them, arguing that I had sold millions of records for them over the years and deserved this indulgence. Peter was impressively game. He had never even encountered a Mexican song in an elevator, didn’t speak a word of Spanish, and would be coproducing with someone who spoke almost no English. I figured they were both gentlemen, and professionals, and would work it out. I was right.

Rubén Fuentes had been involved with Mariachi Vargas during

La Epoca de Oro

, the golden era of mariachi, stretching from the thirties through the fifties. I had grown up loving those records, mostly high-fidelity monaural recordings made in the RCA Victor studios in Mexico City. They had a warm, natural sound, and I was hoping to capture some of that tradition on my own recording. Rubén was pushing for a more modern sound with plenty of echo on the violins and a more urban approach to the arrangements. I met with some resistance when I asked him to replace the modern chords with simpler one-three-five triads. Over the years, Rubén had been largely responsible for diversifying the mariachi style and cultivating a sophisticated urban sheen. To go back to a traditional style understandably seemed like regression to him, but I wanted what I had heard and loved as a child.

I had acquired a very nice black-and-white cow, Luna, who was a pet. She produced an adorable calf, Sweet Pea. I brought all the pictures I had of Luna and Sweet Pea, and tacked them up on the wall in the recording studio. I joked with Rubén in my fractured Spanish that I wanted more cows and fewer car horns in my arrangements. Rubén, who was not used to an artist having an opinion—and most certainly not a female artist—was somewhat vexed. To his credit, he made an earnest effort to compromise. I didn’t want to push him too hard, because I knew he understood the audience that would buy this kind of record better than I did.

Learning to sing all those songs in another language with their enigmatic rhythms was the hardest work I’ve ever done. I didn’t get exactly the sound I wanted from the recording, but the record-buying public didn’t seem to mind.

Canciones de Mi Padre

, released in November 1987, was immediately certified double platinum, sold millions of records worldwide, and is the biggest-selling non-English-language album in American recording history. It won the Grammy for best Mexican-American Performance. I was as surprised as the record company at its success. I have to say that it succeeded on the strength of the material. The songs are strong and beautiful, and are accessible to people who have no knowledge of Spanish. There are many artists who sing the material better than I do, but I was in a position to bring it to the world stage at that particular time, and people resonated to it.

I began to scramble to put together a show. I was friendly with Michael Smuin, who had been artistic director of the San Francisco Ballet for a number of years. A terrific dancer and choreographer, he created a wonderful production of

Romeo and Juliet

, and an interpretation of

Les Enfants du Paradis

, with an Edith Piaf score, that I had adored. He choreographed several short dance pieces to tracks from my Nelson Riddle recordings for prima ballerina Cynthia Gregory, and I had the thrilling experience of

performing them live with her. I had to keep my eyes closed tight when I was on the stage with Cynthia, because if I watched her, I would become mesmerized by her dancing, stand there with my mouth hanging open, and forget to sing. Michael was married to Paula Tracy, also a ballet dancer, and the ballet mistress for many of her husband’s ballets. She and I were close friends.

I wanted a stage director who knew how to move groups of dancers around the stage but would respect the integrity of the traditional dances and leave them intact. I also wanted a theatrical show with good production values to frame the music and make it more understandable to an English-speaking audience.

I called another dear friend, Tony Walton, and asked if he would design my sets. Tony’s movie credits included designing sets and costumes for

Murder on the Orient Express, Mary Poppins

, and

All That Jazz

, for which he won an Oscar. He was also the designer for a long list of successful Broadway shows and many of Michael Smuin’s ballets. He and his wife, Gen, were close friends of the Smuins.

I began to assemble images of what I wanted the show to look like, and Michael, Paula, and I spent hours talking and dreaming together. Paula, while on a trip to Oaxaca, a state in the south of Mexico that is famous for its art, had bought a small wooden box hand-painted in black enamel, with a design bordered in pink roses and other multicolored flowers. I thought that the border design could be used for our proscenium. Tony used that idea and added many wonderful ideas of his own, including a huge fan that unfurled at the beginning of the show and a moving train for a section of songs that I sang about the Mexican Revolution. Jules Fisher came on board as lighting designer. Michael added a fogged stage lit with black light for a dance he created for a song about a ghostly ship with tattered sails (“La Barca de Guaymas”), and also came up with the idea of releasing live white doves at

the end of the show. Two of the doves were trained to fly to my upraised hands and perch on my fingers. I was instructed by the dove wrangler to praise them extravagantly and tell them they did a wonderful job. They never missed a cue.