Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir (12 page)

Read Simple Dreams ~ A Musical Memoir Online

Authors: Linda Ronstadt

By late 1972, John Boylan had helped me to build a solid following performing at colleges, but my records seemed to have hit a discouraging plateau, both artistically and commercially. I was running in one direction trying to please the record company, and in another one trying to please myself. I had been trying to interest the people at Capitol in letting me record “Heart Like a Wheel,” but they saw no commercial potential for it. They wanted me to work with a Bakersfield-style country producer. I thought some good records had come out of Bakersfield, particularly Merle Haggard’s, but I didn’t feel that the style had anything to do with my more eclectic aspirations.

I owed Capitol only one more record. Offers were already coming in from heads of other labels, including Clive Davis at Columbia, Mo Ostin at Warner Bros., and Albert Grossman at his new label, Bearsville. Grossman was Bob Dylan’s manager and he also handled the careers of Peter, Paul and Mary, the Band, and Janis Joplin. The best offer was from David Geffen at his new company, Asylum Records. It was a small label, and its few artists would get a lot of personalized attention. John had spearheaded a successful attempt to get the Eagles signed to Asylum, and it was rapidly becoming a home to singer-songwriters and the L.A. country rock sound,

including Jackson Browne, Joni Mitchell, J. D. Souther, and Judee Sill. I knew I would be in the company of other like-minded artists.

Geffen felt that I could lose the momentum I’d gained if I put out another record that wasn’t promoted properly by a team that understood the direction I was trying to take with my music. He said he thought I should ask Capitol to let him have the next record, and it could have the one after that.

John arranged a meeting with Bhaskar Menon, who was then president of Capitol. I felt a little embarrassed meeting Menon. Herb Cohen had tried unsuccessfully to get me released from Capitol earlier. He had threatened Menon with bad public behavior on my part that could put Capitol in a bad light. It was a bluff, because I hadn’t agreed to any such thing, and it was precisely that kind of artist-as-battering-ram management style that had made me leave Herb. He also encouraged me to think of Menon as the enemy. I had never met him before and was surprised to find a charming, refined, and intelligent gentleman from India with beautiful manners. His sensitive, kindly demeanor was quite a change from the cigar-chomping, hookers-and-cocaine American record industry men I had come to see as a defining stereotype. I listened quietly while my attorney, Lee Phillips, spoke for me. Menon replied that they would like to keep me on the label, suggesting that I needed to choose whether to sing rock or country. I didn’t want to choose. And I wanted to sing “Heart Like a Wheel.”

Menon seemed unpersuaded by Lee Phillips’s skillful presentation, so I decided to speak up for myself. I said, “Please, Mr. Menon, let me go. I don’t want to be here, I don’t fit here, and, besides, you don’t need me. You have two other female singers, Helen Reddy and Anne Murray, selling lots of records for you. Let me go!” To our collective surprise, he relented. I was free to sign with Geffen.

7

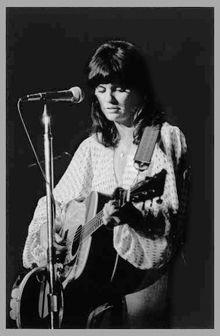

Neil Young Tour

Photo by Henry Diltz.

I

N

J

ANUARY

1973 D

AVID

Geffen called John Boylan and said that he wanted me to join the upcoming Neil Young tour as the opening act. I was reluctant, to say the least, because my show and my band were set up to play small clubs, and our first concert with Neil was going to be at Madison Square Garden. David and John knew what a boost the huge exposure to audiences across the country would give my record sales, and they talked me into it. With just a few days’ notice, we were off to New York City.

That night, a few songs into Neil’s set, someone handed him a note saying that National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger had reached an agreement in Paris ending the United States’s involvement in Vietnam. Neil announced simply, “The war is over.” The audience of eighteen thousand exploded, cheering, crying, and

screaming for the next ten minutes. In the middle of all the pandemonium, I was huddled in a corner wrestling with the fact that I was still a club act with a not very loud kind of folky band, no discernible stage patter, and no clue how to reach a crowd like that.

I changed backup singers, stage clothes, and attitudes for three months (seventy-eight shows), as we worked our way back west across the country. I was encouraged nightly by the side stage presence of Neil’s piano player, Jack Nitzsche, who, in addition to being a really good piano player, was a really mean drunk. He told me with metronomic regularity that as a singer and performer, I was not up to the task of opening for Neil, and that he was going to talk Neil into hiring soul singer Claudia Lennear or singer-songwriter Jackie DeShannon to replace me. Even though I basically shared his opinion, I wasn’t going to let a mean drunk shove me off the stage, and I continued to see what I could do to improve. I also watched Neil, who was nothing but nice to me, play his show every single night, and I continue to find him one of the purest singers and most uniquely gifted songwriters in contemporary music. Hearing his eerie, prairie-wind howl of a voice—a boy soprano fuel-injected with testosterone—in such regular and concentrated doses was a huge part of my musical education and an enduring pleasure.

The tour was traveling in a chartered Lockheed Electra turboprop airliner. On board were assorted managers, Neil’s band, my band, and a few members of the sound crew. The stewardess was Linda Keith, who was married to Neil’s pedal steel player, Ben Keith. She did her job with friendly efficiency and appeared cheerfully unaware of the substances that were being ignited or hoovered by some of the passengers during the flights. I was happy that she also kept us supplied with fresh fruit. She probably saved us from scurvy.

In late February, we landed at Houston Intercontinental

Airport. We were booked for a concert at the Sam Houston Coliseum, a ten-thousand-seat hockey arena, with the following night off in Houston before we pushed on to Kansas City, Missouri. When we got to the hotel, we ran into Eddie Tickner, who was Gram Parsons’s manager. He told us that Gram and Emmylou Harris, the new girl he was singing with, were playing at a well-known Houston honky-tonk called Liberty Hall.

Chris Hillman of the Byrds, and later Gram’s bandmate in the Flying Burrito Brothers, had told me one night that he and Gram had met Emmylou in Washington, D.C., and loved her singing. He said he felt we really needed to meet each other—that we were pursuing similar ideas in our music—and he was certain we would like each other. I was excited to get the chance to experience for myself what Chris had been talking about and asked John Boylan if he would make arrangements for the two of us to see their show after we finished playing ours that night.

We arrived at Liberty Hall to find it filled with members of a club called the Sin City Boys. They were plenty rowdy, but when Gram and Emmylou started to sing, it got very quiet. Clearly, something unusual was taking place up on that stage, and we in the audience were mesmerized. Emmy has the ability to make each phrase of a song sound like a last desperate plea for her life, or at least her sanity. No melodrama; just the plain truth of raw emotion. The sacred begging the profane.

My reaction to it was slightly conflicted. First, I loved her singing wildly. Second, in my opinion, she was doing what I was trying to do, only a whole lot better. Then came a split-second decision I made that affected the way I listened to and enjoyed music for the rest of my life. I thought that if I allowed myself to become envious of Emmy, it would be painful to listen to her, and I would deny myself the pleasure of it. If I simply surrendered to loving what she did, I could take my rightful place

among the other drooling Emmylou fans, and then maybe, just maybe, I might be able to sing with her.

I surrendered.

Back at the hotel, we told Neil about what a great show it had been. He and his band, the Stray Gators, plus members of my band, went with us the following night. Gram and Emmy did another great show, and Neil and I sat in at the end. Someone had given Gram and Emmy jackets with the words

Sin City

stitched on the back. One of the Sin City Boys came up to the stage and presented one to me. I wore it for years. After the show, the owner of Liberty Hall hosted a party in the big dressing room upstairs.

That’s when the trouble started. Jack Nitzsche came over, put his arm around me, and began to speak in a very complimentary way. Then gradually what he said became abusive. I was used to the nightly routine of cutting remarks and tried to move away. Because he was a keyboard player, he had powerful arms and had me locked in a tight grip. He continued to slur the cruelest and most insulting things he could muster in his inebriated state. I asked him to let me go. He said that he was going to make me fight my way out. It became obvious to me that he wanted to make an ugly scene, and I didn’t want a big fight with Jack to spoil the wonderful evening we had just had with Gram and Emmy. Still, his mean-spirited bullying had frightened me, and, though I tried hard not to, I began to cry. John Boylan, my drummer, Mickey McGee, and my pedal steel player, Ed Black, noticed from across the room that I was upset, and moved in to help me. With three husky men in my corner, Nitzsche backed off.

We decided to go back to the hotel. Downstairs, there were two or three waiting limos. We climbed into the first one in line and found Gram and his wife, Gretchen, already waiting inside. Just as we began to pull away from the curb, there was a knock on the window, and Jack stumbled into the front seat. He

turned around and began talking through the partition. “You’re a mess, Gram,” he said. “You’re fucked up.” Gram’s reaction was to wonder out loud why the kettle was calling the pot such a deep shade of black. Jack kept at him. “You’re a junkie, Gram. You’re going to die. Danny Whitten’s dead, and you’re next,” he said, referring to the Crazy Horse guitarist who had died of an overdose just three months before. Gretchen started to cry. Boylan reached forward and closed the partition to shut Jack up.

Gram and Neil wanted to play music some more, so we went to Neil’s suite and began to play all the country songs we knew. Emmy wasn’t there. We were going through the familiar George Jones, Hank Williams, and Merle Haggard repertoire. Gram and Neil were showing some of their new songs. We were having fun for a while, but Jack went over to the electric keyboard in Neil’s room and began pounding nonsense chords. Then he stood up and said, “Your music sucks! I’m going to show you what I think of your music!” He walked over to the middle of the room, unzipped his pants, and began to pee on the floor. Gram threw Jack’s hat under the stream, and he wound up peeing in his own hat.

I was out the door. John took me back to my room. I was exhausted and in floods of tears. There was a knock at the door. It was Emmy. She had heard about what had happened with Jack and had come over to try to make me feel better. She brought me a yellow rose. I pressed the rose, and I still have it in a box somewhere. I still have Emmy too.

Years later, after Jack had experienced a period of sobriety, he apologized to me. Looking back, I imagine he genuinely didn’t care for my singing, and he was entitled to that. He’d have found me somewhat in agreement, as I was still learning and, in the beginning, way over my head while struggling to perform in those huge arenas. It turned out that I was plenty tough enough to survive the nightly onslaught of his drunken insults. Jack was a stellar musician

and arranger, with impressively written arrangements for Phil Spector (“River Deep, Mountain High” by Tina Turner) and the Rolling Stones (“You Can’t Always Get What You Want”) already to his credit. What I thought was tragic, seeing him act that way, was that he deprived himself of the opportunity to operate in the world with the grace and dignity of which he was fully capable.

The morning after the unfortunate incident in Neil’s hotel room, everyone climbed on board the plane and acted like nothing had happened. Someone from Neil’s organization must have leaned on Jack and told him to get off my case, because after that, he left me alone. The tour lasted five more weeks. I had a great time.