Simeon's Bride

ALISON G. TAYLOR

To my husband Geoffrey

and

my children Aaron and Rachel

‘For what is marriage?

A little joy, and then a chain of sorrows’

Maria Magdalena van Beethoven (1746–1787

[Mother of Ludwig van Beethoven]

to Cäcilia Fischer, a neighbour

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Autumn: Prologue

Spring: Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Epilogue

Copyright

Up the path beside the graveyard, skirting puddles which never dried out from one rainstorm to the next, John Jones went with the edgy gait of an old dog, cursing as his ankle turned on a loose stone, and mud spattered over the toe of his boot and up his trouser leg. He looked behind him for the hundredth time, but saw only dripping trees and rank undergrowth, heard only wind in the deep woods, whining through creaking, snapping branches. He prayed it was only the wind, and not the white-faced man come to breathe the dirty stink of death in his frightened old face.

At the top of the path, where the tarmac lane stopped dead by the church gates, he leaned against the wall to get his breath, thinking his life a sorry mess if he was too afraid to stay in his own house and must seek some human company; even his dreary nagging wife better company than the monsters of the imagination. He peered down the lane, past the school with its yard and classrooms empty for the weekend, to the row of low cottages beyond, where his wife was doubtless gossiping with her cronies over cups of tea in Mary Ann’s parlour. Pushing his scrawny body away from the wall, he slid off along the lane, wondering who the man might be, knowing, as night followed day, that such pursuit boded ill for the health of John Jones. The man had been told to follow him, told to worry him like a rogue dog after sheep, told to wait until Chance smirked, then told to pick up a stone or a heavy branch and smash the living daylights out of his head.

He rubbed his scalp, the skull so thin and fragile beneath its pelt of matted dirt-grey hair, knowing how easily he could be destroyed; head crushed and all of himself inside obliterated, along with all the secrets: secrets locked away from the prying noses of his wife and the rest of the world, secrets known only to God. But that was the root of his trouble and terror, because not only God was privy to some of those secrets.

Thumping on Mary Ann’s door with a huge fist at the end of his skinny long arm, still looking behind him, John Jones wondered how much money the man had demanded to do the deed, how much it was worth to have John Jones’s mouth and eyes and ears shut for ever. Was

he worth more dead than alive, like a carcase at Clutton’s slaughterhouse? He shivered, waiting for the old woman to creep on her fat rheumaticky legs to open her door, thinking his pursuer might be a gippo from the site down the main road, happy to crunch an old man’s skull to bloody splinters for the price of a packet of baccy, or even for nothing and just for the hell of it. John Jones decided, as he heard Mary Ann fumbling with her lock, it was time to put a stop to it all, to redeem the time the other one planned to steal. Time to take the lid off the can of worms. He snickered to himself, for it was more a can of maggots by now.

‘She’s not here,’ Mary Ann said. ‘She’s doing messages for me.’

‘Where’s she gone then, old woman?’

‘Less of the old woman from you!’ Mary Ann snarled. ‘Whore’s dog!’ She spat at him, and slammed the door in his face, leaving him marooned on her polished doorstep. He deliberately scuffed his dirty boots on the purply slate, scarring the sheen with filth, before trailing off down the lane, away from the church, towards the main road. He looked behind again, then sat on the garden wall of somebody’s house, making a roll-up, cogitating on his plight, and the fear scouring like poison through his bowels.

Sunshine cut the tattered rags of storm cloud, warming his face, making the sweat rise. He lit his cigarette, pungent smoke curling in the air with the stink of his body, remembering what he had seen in those dark woods. The memory stirred him from the wall, gave his feet a life of their own, to pace the square of weedy grass at the roadside, and to kick their owner for his stupidity. He could have rid himself of his job, thrown the pittance of a wage back in the arrogant face of the castle gentry, abandoned the rancid hovel in which he lived, and the poverty suffocating his smallest dream, trampling it into the dirt before it even took shape. And best of all, he could be rid of his wife, the one ugly enough to frighten the Devil from his den.

He sat again on sun-warmed stone, smelling the scents of late-blooming roses in the garden behind him, watching leaves flutter down from the trees to lie in drifts of gold and copper-brown against walls and tree boles, and looked at the manicured acreage lavished with flowering shrubs and succulent roses in pinks and yellows and ivory white. He stared at the cottage within the garden and felt envy enough to break the stoutest heart, recalling the other cottage, its reek of wealth, the rich fat furniture, deeper and more tempting than the breasts and thighs of any wench. He sighed, shaking his head to nudge the memories out of the darkness where he thrust them long months before. It was not too late even now. John Jones ground his jaw, stumps of teeth crunching together, and called himself worse than a fool. He spat on the ground, a phlegmy globule which lay glistening in the sunshine before

sliding off the edge of a dead leaf. In his mind’s eye, he saw the man staring at him from the night-dark trees, eyes glittering like black coals, face white as death. He shivered violently, thinking the man might have set a trap in the deepest woods, a gin-trap big enough to snare him, strong enough to hold him until his death throes ceased.

Jumping to his feet, he loped back to the village, sticking up two fingers as he passed Mary Ann’s cottage, and on to the path to his own place, head high, fear quenched by resolve and the prospect of a brighter dawn to come. Time for the other one to have some shocks, he said to himself. A taste of their own bitter medicine might sicken enough to stop the flaunting and the sneering, the swaggering in that fancy car. He licked his lips, tasting revenge. Folk said money stank, and it was time the stench in John Jones’s house and about his person took on another flavour. He started whistling, a shrill rendering of ‘Bread of Heaven’, his ugly wife’s favourite hymn, and scuffed his way back down the path beside the graveyard.

Tall and dark and, in the eyes of most of the women and not a few of the men who saw him about his daily business, more than a little handsome, Dewi Prys, twenty-seven years old come June, when he would have been a policeman for exactly eight years, a detective for almost three, and reared on the big council estate just outside Bangor city, hastily folded up the

Daily

Post

and pushed it under a sheaf of files when he heard Jack Tuttle walking up the stairs from the cell block. Dewi had little time for the inspector. Born and bred in gentler territory near the English border, Jack knew nothing of hardship and isolation, of melancholia scavenging a man’s soul through long days and nights when rain and wind stalked the mountains, beating against doors and rattling draughty windows, threatening invasion like marauding English, or when God wrapped village and chapel and earth and trees in a pall of mountain mist as stifling as all the guilt in Christendom.

Dewi looked up. ‘What did our young friend in the cells want, sir?’ he asked. ‘Did he confess? Did he say “Yes sir, it was me nicked the video from Dixon’s in Caernarfon and took it back a week later to Dixon’s in Bangor for a refund?” I’ll bet he didn’t, did he?’

Jack sat down. ‘He wanted to speak to the chief inspector. So he could speak Welsh.’

‘Mr McKenna’s not on duty ’til Monday, is he?’ Dewi said. ‘Wouldn’t he tell you, then?’

‘Well,’ Jack said, ‘in among a lot of garbage about how it was his right to be able to speak in his own language – the language of the hearth, as he calls it – your mate Ianto told me Jamie Thief has two ladyfriends and a fancy car.’

‘Very into nationalism, is Ianto,’ Dewi said. ‘Been known to do his fair share of rabble-rousing with the Welsh Language lot.’ He leaned back, and crossed his legs. ‘He’s not really a mate of mine, sir. I just happen to know him because he lives on the estate; so I can’t help it if I hear he’s bragging about spraying paint on walls by the new road, can I? Ianto reckons it was him wrote that rude message about the Queen just before she opened Conwy Tunnel.’

‘Did you hear me, Prys?’ Jack snapped. ‘He said Jamie has a new car. What d’you know about it?’

‘Nothing,’ Dewi said. ‘You actually said, sir, that Ianto said Jamie has a fancy car. Or, maybe, a ladyfriend with a fancy car.’ He paused. ‘Or even, two ladyfriends.’

‘Well?’ Jack snapped; Dewi thought, like an evil-tempered little dog.

‘Well Jamie’s never had a problem pulling the women,’ Dewi observed.

‘What’s that got to do with it?’

‘Nothing, most probably. He’s making hay. He’ll be inside again before long.’

‘Why? What for?’

‘Don’t know yet, do we? But Jamie’s always done

something

. It’s just a matter of waiting to find out what, then dropping on him.’

Jack tapped a pencil tip on the desk. ‘I suppose I should’ve asked your mate for a few details.’

‘Wouldn’t be much point to that. He’d only tell you a tale … in any language. He’s probably hoping to set us on Jamie to pay him back for something. Anyway,’ Dewi continued, ‘Jamie hasn’t got a car. I’d know, wouldn’t I, seeing how he only lives a few doors from my nain. Somebody wants to see us, by the way. The duty officer called through.’

‘Who?’

‘John Beti.’

‘Who’s he?’

‘John Jones. Beti Gloff’s husband.’

‘And who, Prys, is Beti Gloff?’

‘Lame Beti, sir. From Salem village,’ Dewi said. ‘Beti Gloff.’

‘Why’s she called Beti Gloff and not Beti Jones?’

‘She is called Beti Jones, sir.’ Dewi sighed. ‘Gloff means lame in Welsh.’

‘Oh,’ Jack said. ‘So what does her husband want with us?’

‘Don’t know, do I? Nobody said.’

‘We’d better find out, then, hadn’t we? Bring him into my office.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Prys?’ Jack stopped by the door. ‘What do we know about this John Jones? Does he have a record? Always as well to know your villains, isn’t it?’

‘I wouldn’t call John Beti a villain. Don’t reckon he’s got the belly for it. He’s been done for this and that over the years, mostly thieving … we thought he pinched some detonators from Dorabella Quarry a while back, but it wasn’t him.’

‘Who was it, then?’ Jack asked. ‘One of the terrorist lot? What’s the expression, Prys? The joke about fire-bombing Welsh properties so the English can’t buy them?’

Dewi sighed again. ‘Something along the lines of “Come home to a nice warm fire in a Welsh cottage”, sir,’ he said. ‘A local farmer nicked the detonators to blow up a tree-stump in the middle of his best arable field.’

‘That’s bloody typical, isn’t it?’ Jack said. ‘Why on earth didn’t he just go out and buy some?’

John Jones sat in the chair beside Jack’s desk, making a roll-up. In between spreading shreds of tobacco on grubby paper, licking the edge of the paper with flicks of a thin and pointed tongue, he smirked at Dewi. Dropping a match into the wastebin, after dousing its flame with a calloused thumb, he said, ‘Put you in long pants now, have they, Dewi Prys?’

‘Why did you want to see us, Mr Jones?’ Jack asked.

‘Got something for you, haven’t I?’

‘Have you?’ Jack said.

‘Yes.’ He smirked again. ‘Doing your job for you, I am.’

‘Are you?’ Dewi intervened. ‘How’s that, then?’

‘Found you a body, didn’t I?’ John Jones looked from Jack to Dewi, looking for a pat on the back, Dewi thought, and thought he would rather send him back to his hovel with a flea in his ear to keep company with those infesting his bed.

‘Where is it, then, John Betti?’ Dewi asked. ‘Where’s this body you’ve so kindly found for us?’

John Jones turned to Jack. ‘You should do something with him,’ he said, flicking a thumb towards Dewi. ‘Got a gob on him like a parish oven.’

Jack fidgeted. ‘Where’s the body?’

‘In the woods, isn’t it?’

‘We don’t know, do we?’ Dewi said. ‘We’re trying to find out. Which woods is it supposed to be in?’

‘What d’you mean? “Supposed to be”?’ John Jones screeched. ‘It’s not

supposed

to be anywhere! It’s in Castle Woods. I’ve seen it there, haven’t I?’

‘If you say so,’ Dewi said.

‘Who is it?’ Jack demanded.

‘Who is it?’ John Jones repeated, raising meagre eyebrows. ‘How the fuck should I know? It’s all bones and rags.’

Dewi and John Beti in the car with him, Jack turned off the expressway on to the narrow old road by Salem village, crossed Telford’s graceful bridge spanning the river, and stopped outside high blue gates guarding one of the private entrances to Snidey Castle Estate. Glimpsing John Jones’s thin face as he suddenly shifted on the seat, Jack thought the man like a fairy-tale character: wizened and strange and not quite real.

‘I see the crime-scene lot beat us to it,’ he said, pointing towards the

white van parked over the road. He turned to John Jones. ‘How far into the woods were you when you saw the body?’

‘Dunno. Maybe a mile from here. Maybe a bit more. I wasn’t taking much notice, just wandering round.’

‘Doing what?’ Dewi asked. ‘Poaching?’

‘Minding my own fucking business, Dewi Prys! You should try it sometime.’

Dewi unbuckled his seat belt. ‘

You

should try minding your mouth!’ He climbed out of the car, and looked back up the road. As night drew near, cloud again massed behind the mountains, in the wake of a gale still not spent. Broken twigs littered the verges, drops of rain spattered here and there. The wind, turned during the night, carried a harsh chill from the north-west, and in the distance, drifts of snow left over from earlier storms lay deep and treacherous in mountain hollows and crevices. By morning, Dewi thought, the mountains above Dorabella Quarry would be capped with a fresh fall.

Anxious to be out of a car beginning to smell of something odd and stale and rather unwholesome, Jack followed. Taking Wellingtons from the boot, he changed, placing his shoes neatly in their own space, eyeing the nut-brown leather with distaste as a spiteful jibe, mouthed by Ianto in the cells under the police station, returned to taunt him. A brown nose, Ianto called him, and accused him of trying to trample McKenna into the mud to gain promotion. Then, staring long and hard at Jack’s shoes, Ianto had said, ‘Come to think of it, Mr Inspector, I daresay folk has problems seeing anything but the soles of your fancy shoes at times.’

‘Are we to wait for the chief inspector, sir?’ Dewi asked.

‘I haven’t been in touch,’ Jack said. ‘No need to disturb him until we know what’s what. Let’s get on with it. It’ll be dark before long.’

‘We’d better mark the way with this, then,’ Dewi said, pulling a roll of Dayglo plastic tape from the van. ‘Like Theseus in the maze, going after the Minotaur. Wouldn’t want to get lost, would we?’

‘Fat chance!’ John Jones sneered. ‘Could smell you lot under fifty fucking feet of water, never mind in a few trees!’

A short way along a gravelled lane driven through ranks of tall Scotch pine, John Jones stopped to get his bearings before plunging down a muddy slope into the trees. Knotting tape round a tree trunk, Dewi followed the others into the deep woods where pine gave way to slender columns of birch and alder, close-grown elm trees rotten with disease, their branches tangled into crippled distortions, as if the struggle for light had proved beyond their strength. John Jones moved hesitantly forward, standing now and then to look for signs of earlier passage, while dead leaves from a hundred autumn falls lay sodden underfoot, mouldering and dirty, the stench of decay filling the air.

‘How often d’you reckon people come down here?’ Jack asked him. He shrugged, and ploughed on without a word, down a steep incline towards the river, its slimy banks littered with outcrops of pale marbled rock. Wellingtons skidding, Jack almost tumbled in, and Dewi caught his arm, hauling him upright.

‘You could hide a hundred bodies down here and nobody’d ever find them,’ Dewi observed. He turned to John Jones. ‘Funny how you managed, isn’t it?’

By the river, waters creaming in spate over rock debris and glittering gravel on the river-bed, the light was magnificent, filled with steely-blue and grey-white tones, the sun long obscured behind thick winter cloud driven hard and fast by winds off the sea. Branches creaked in the heavy silence, yet the air remained so still it was like, Jack fancied, being submerged. Wherever he looked, he saw trees: sombre, dark trees, some frosted with the sharp livid green of budding foliage, others dying, life choked out by dark tendrils of ivy. Along the riverbanks, lichen-covered rocks tumbled, wrapped in fronds of dead bracken. No birdcall broke the stillness, no small animals scuttered in the undergrowth; nothing relieved the grandeur and symmetry of nature reclaiming its own. His eye caught the drift of a shadow within the phalanx of trees directly ahead, and he stared, trying to make sense of the mass of grey and mouldy green splashed in his line of sight like drab colour running from a painter’s careless brush strokes.

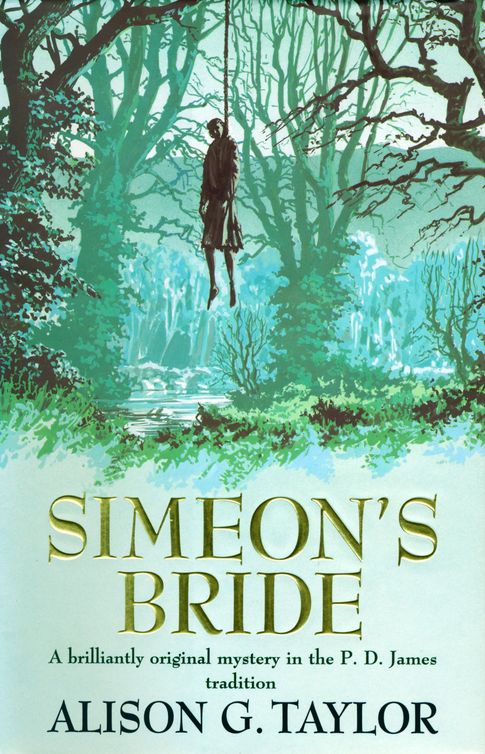

John Jones moved forward, boots squelching. ‘It’s there. I can see it.’ Slowly, almost reluctantly, they followed the crabbed figure. On a mound within the woods, amid a convolution of dead trees throttled with ivy, the body, barely more substantial than the shadow of a shadow, swung on the end of frayed rope, clothes which had once been black hanging in grey tatters about its limbs. Little fillets of dried flesh still clung here and there; a few tufts of matted hair sprouted from its head. The eyes were long gone, a feast for the crows and magpies. Jack looked upon their find, and his scalp crawled. How many days and nights had she hung there, drenched by rain, scalded by the summer sun, scoured by the winds, and made brittle by deep mid-winter frost?

The corpse dangled close to the ground, rope and neck and spine and legs stretched by gravity and damp: elongated into some surrealistic form, feet pointing like those of a dancer, motion frozen in mid jump. A ragged skirt swung with a life of its own, giving off heady puffs of some strange scent. Touching nothing, in fear of damaging the frail remains, Jack examined the body. As he moved around, it seemed to swing after him, attracted by a strange magnetism, the head leaning forward to watch his progress. He felt its hip brush his shoulder, and almost screamed with terror.

A suicide, he decided, and a typical way for a woman to kill herself.

He stood behind her, that strange scent drying the back of his throat, and looked at what remained of her hands, crippled and clawed below the thick leather strap which bound her wrists tight together like those of the convict ready for execution.