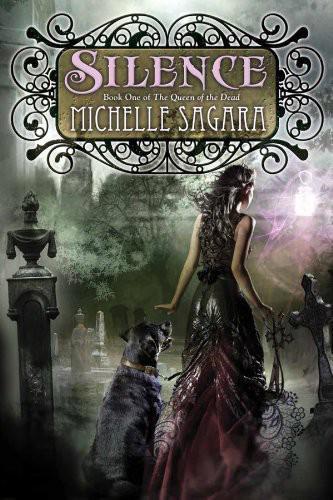

Silence

Authors: Michelle Sagara

SILENCE

SILENCE

Book One of The Queen of the Dead MICHELLE SAGARA

DAW BOOKS, INC.

DONALD A. WOLLHEIM, FOUNDER

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

ELIZABETH R. WOLLHEIM

SHEILA E. GILBERT

PUBLISHERS

PUBLISHERS

http://www.dawbooks.com

Copyright © 2012 by Michelle Sagara.

ISBN: 978-1-101-64245-0

All Rights Reserved.

Jacket art by Cliff Nielsen.

DAW Book Collectors No. 1585.

DAW Books are distributed by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Book designed by Elizabeth Glover.

All characters in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead is strictly coincidental.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal, and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage the electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Nearly all the designs and trade names in this book are registered trademarks. All that are still in commercial use are protected by United States and international trademark law First Printing May 2012

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

This is for the girls:

Calie

Katie

Caroline

Moly

Alexandra

Rada

With thanks, with gratitude, although admittedly they might not understand why.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book was a bit of a departure for me, and with departures, I generaly pester my friends, because I’m less certain of myself. Chris Szego, who manages the bookstore at which I stil work part-time (because it’s about the books), was hugely encouraging. And nagging. In about that order. So were hugely encouraging. And nagging. In about that order. So were Karina Sumner-Smith and Tanya Huff.

And, of course, Thomas and Terry had to read the book a chapter a time, because that’s what alpha readers are for.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Eighteen

About the Author

EVERYTHING HAPPENS AT NIGHT.

EVERYTHING HAPPENS AT NIGHT.

The world changes, the shadows grow, there’s secrecy and privacy in dark places. First kiss, at night, by the monkey bars and the old swings that the children and their parents have vacated; second, longer, kiss, by the bike stands, swirl of dust around feet in the dry summer air. Awkward words, like secrets just waiting to be broken, the struggle to find the right ones, the heady fear of exposure—what if, what if—the joy when the words are returned. Love, in the parkette, while the moon waxes and the clouds pass.

Promises, at night. Not first promises—those are so old they can’t be remembered—but new promises, sharp and biting; they almost hurt to say, but it’s a good hurt. Dreams, at night, before sleep, and dreams during sleep.

Everything, always, happens at night.

Emma unfolds at night. The moment the door closes at her back, she relaxes into the cool breeze, shakes her hair loose, seems to grow three inches. It’s not that she hates the day, but it doesn’t feel real; there are too many people and too many rules and too many questions. Too many teachers, too many concerns. It’s an act, getting through the day; Emery Colegiate is a stage. She pins up her hair, wears her uniform—on Fridays, on formal days, she wears the stupid plaid skirt and the jacket—goes to her classes. She waves at her friends, listens to them talk, forgets almost instantly what they talk about. Sometimes it’s band, sometimes it’s class, sometimes it’s the other friends, but most often it’s boys.

often it’s boys.

She’s been there, done al that. It doesn’t mean anything anymore.

At night? Just Petal and Emma. At night, you can just be yourself.

Petal barks, his voice segueing into a whine. Emma puls a Milk-Bone out of her jacket pocket and feeds him. He’s overweight, and he doesn’t need it—but he wants it, and she wants to give it to him. He’s nine, now, and Emma suspects he’s half-deaf. He used to run from the steps to the edge of the curb, half-dragging her on the leash—her father used to get so mad at the dog when he did.

He’s a rottweiler, not a lapdog, Em.

He’s just a puppy.

Not at that size, he isn’t. He’ll scare people just by standing still; he needs to learn to heel, and he needs to learn that he can hurt you if he drags you along.

He doesn’t run now. Doesn’t drag her along. True, she’s much bigger than she used to be, but it’s also true that he’s much older. She misses the old days. But at least he’s stil here. She waits while he sniffs at the green bins. It’s his little ritual. She walks him along the curb, while he starts and stops, tail wagging.

Emma’s not in a hurry now. She’l get there eventualy.

Petal knows. He’s walked these streets with Emma for al of his life. He’l folow the curb to the end of the street, watch traffic pass as if he’d like to go fetch a moving car, and then cross the street more or less at Emma’s heel. He talks. For a rottweiler, street more or less at Emma’s heel. He talks. For a rottweiler, he’s always been yappy.

But he doesn’t expect more of an answer than a Milk-Bone, which makes him different from anyone else. She lets him yap as the street goes by. He quiets when they approach the gates.

The cemetery gates are closed at night. This keeps cars out, but there’s no gate to keep out people. There’s even a footpath leading to the cement sidewalk that surrounds the cemetery and a smal gate without a padlock that opens inward. She pushes it, hears the familiar creak. It doesn’t swing in either direction, and she leaves it open for Petal. He brushes against her leg as he slides by.

It’s dark here. It’s always dark when she comes. She’s only seen the cemetery in the day twice, and she never wants to see it in daylight again. It’s funny how night can change a place. But night does change this one. There are no other people here.

There are flowers in vases and wreaths on stands; there are sometimes letters, written and pinned flat by rocks beneath headstones. Once she found a teddy bear. She didn’t take it, and she didn’t touch it, but she did stop to read the name on the headstone: Lauryn Bernstein. She read the dates and did the math. Eight years old.

She half-expected to see the mother or father or grandmother or sister come back at night, the way she does. But if they do, they come by a different route, or they wait until no one—not even Emma—is watching. Fair enough. She’d do the same.

But she wonders if they come together—mother, father, grandmother, sister—or if they each come alone, without grandmother, sister—or if they each come alone, without speaking a word to anyone else. She wonders how much of Lauryn’s life was private, how much of it was built on moments of two: mother and daughter, alone; father and daughter, alone.

She wonders about Lauryn’s friends, because her friends’ names aren’t carved here in stone.

She knows about that. Others wil come to see Lauryn’s grave, and no matter how important they were to Lauryn, they won’t see any evidence of themselves there: no names, no dates, nothing permanent. They’l be outsiders, looking in, and nothing about their memories wil matter to passing strangers a hundred years from now.

Emma walks into the heart of the cemetery and comes, at last, to a headstone. There are white flowers here, because Nathan’s mother has visited during the day. The lilies are bound by wire into a wreath, a fragrant, thick circle that perches on an almost invisible frame.

Emma brings nothing to the grave and takes nothing away. If she did, she’s certain Nathan’s mother would remove it when she comes to clean. Even here, even though he’s dead, she’s stil cleaning up after him.

She leaves the flowers alone and finds a place to sit. The graveyard is awfuly crowded, and the headstones butt against each other, but only one of them realy matters to Emma. She listens to the breeze and the rustle of leaves; there are wilows and oaks in the cemetery, so it’s never exactly quiet. The sound of passing traffic can be heard, especialy the horns of pissed-off drivers, but their lights can’t be seen. In the city this is as close to

drivers, but their lights can’t be seen. In the city this is as close to isolated as you get.

She doesn’t talk. She doesn’t tel Nathan about her day. She doesn’t ask him questions. She doesn’t swear undying love.