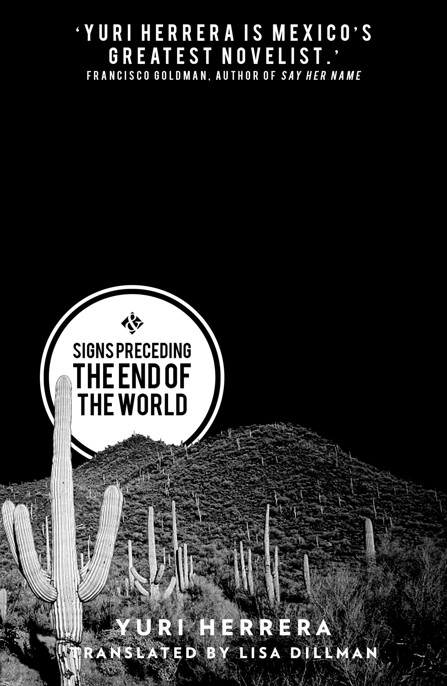

Signs Preceding the End of the World

Read Signs Preceding the End of the World Online

Authors: Yuri Herrera

Tags: #Contemporary Fiction, #Literary Fiction, #Novel, #Translation, #Translated fiction, #Rite of passage, #Spanish, #Mexico, #Latin America, #USA, #Rio Grande, #Yuri Herrera, #Juan Rulfo, #Roberto Bolaño, #Jesse Ball, #Italo Calvino, #Kafka, #Kafkaesque, #Makina, #Underworld, #People-smuggling, #trafficking, #Violence, #Illegal Immigrants, #Immigration, #Undocumented workers, #Machismo, #Gender, #Coyote, #Coyotaje, #Discrimination, #Brother, #Borderlands, #Border crossing, #Frontiers, #Jobs in the US, #Trabajos del Reino, #Señales que precederán al fin del mundo, #Signs Preceding the End of the World, #La transmigración de los cuerpos, #The Transmigration of Bodies

1

THE EARTH

I’m dead, Makina said to herself when everything lurched: a man with a cane was crossing the street, a dull groan suddenly surged through the asphalt, the man stood still as if waiting for someone to repeat the question and then the earth opened up beneath his feet: it swallowed the man, and with him a car and a dog, all the oxygen around and even the screams of passers-by. I’m dead, Makina said to herself, and hardly had she said it than her whole body began to contest that verdict and she flailed her feet frantically backward, each step mere inches from the sinkhole, until the precipice settled into a perfect circle and Makina was saved.

Slippery bitch of a city, she said to herself. Always about to sink back into the cellar.

This was the first time the earth’s insanity had affected her. The Little Town was riddled with bullet holes and tunnels bored by five centuries of voracious silver lust, and from time to time some poor soul accidentally discovered just what a half-assed job they’d done of covering them over. A few houses had already been sent packing to the underworld, as had a soccer pitch and half an empty school. These things always happen to someone else, until they happen to you, she thought. She had a quick peek over the precipice, empathized with the poor soul on his way to hell. Happy trails, she said without irony, and then muttered Best be on with my errand.

Her mother, Cora, had called her and said Go and take this paper to your brother. I don’t like to send you, child, but who else can I trust it to, a man? Then she hugged her and held her there on her lap, without drama or tears, simply because that’s what Cora did: even if you were two steps away it was always as if you were on her lap, snuggled between her brown bosoms, in the shade of her fat, wide neck; she only had to speak to you for you to feel completely safe. And she’d said Go to the Little Town, talk to the top dogs, make nice and they’ll lend a hand with the trip.

She had no reason to go see Mr. Double-U first, but a longing for water led her to the steam where he spent his time. She could feel the earth all the way under her nails as though she’d been the one to go down the hole.

The sentry was a proud, sanguine boy who Makina had once shucked. It had happened in the awkward way those things so often do, but since men, all of them, are convinced that they’re such straight shooters, and since it was clear that with her he’d misfired, from then on the boy hung his head whenever he ran into her. Makina strolled past him and he came out of his booth as if to say No one gets through, or rather Not you, you’re not getting through, but his impulse lasted all of three seconds, because she didn’t stop and he didn’t dare say any of those things and could only raise his eyes authoritatively once she’d already gone by and was entering the Turkish baths.

Mr. Double-U was a joyful sight to see, all pale roundness furrowed with tiny blue veins; Mr. Double-U stayed in the steam room. The pages of the morning paper were plastered to the tiles and Mr. Double-U peeled them back one by one as he progressed in his reading. He looked at Makina, unsurprised. What’s up, he said. Beer? Yeah, Makina said. Mr. Double-U grabbed a beer from a bucket of ice at his feet, popped the top with his hand and passed it to her. They each uptipped the bottle and drank it all down, as if it were a contest. Then in silence they enjoyed the scuffle between the water inside and the water outside.

So how’s the old lady? Mr. Double-U inquired.

A long time ago, Cora had helped Mr. Double-U out; Makina didn’t know what had happened exactly, just that at the time Mr. Double-U was on the run and Cora had hidden him till the storm blew over. Ever since then, whatever Cora said was law.

Oh, you know. Alive, as she likes to say.

Mr. Double-U nodded, and then Makina added She’s sending me on an assignment, and indicated a cardinal point.

Off to the other side? Mr. Double-U asked. Makina nodded yes.

Ok, go, and I’ll send word; once you’re there my man will get you across.

Who?

He’ll know you.

They sat in silence once more. Makina thought she could hear all the water in her body making its way through her skin to the surface. It was nice, and she’d always enjoyed her silences with Mr. Double-U, ever since she first met him back when he was a scared, skinny animal she brought pulque and jerky to while he was in hiding. But she had to go, not just to do what she had to do, but because no matter how tight she was with him, she knew she wasn’t allowed to be there. It was one thing to make an exception, and quite another to change the rules. She thanked him, Mr. Double-U said Don’t mention it, child, and she versed.

She knew where to find Mr. Aitch but wasn’t sure she’d be able to get in, even though she knew the guy guarding the entrance there, too: a hood whose honeyed words she’d spurned, but she knew what he was like. They said he’d offed a woman, among other things; left her by the side of the road in an oil drum on orders from Mr. Aitch. Makina had asked him if it was true back when he was courting her, and all he said was Who cares if I did or not, what counts is I please ’em all. Like it was funny.

She got to the place.

Pulquería Raskolnikova

, said the sign. Beneath it, the guard. This one she couldn’t swish past, so she stopped in front and said Ask him if he’ll see me. The guard stared back with glacial hatred and gave a nod, but didn’t budge from the door; he stuck a piece of gum in his mouth, chewed it for a while, spat it out. He eyed Makina a little longer. Then turned half-heartedly, as though about to take a leak simply to pass the time, sauntered into the cantina, came back out and leaned against the wall. Still saying nothing. Makina snorted and only then did the guard drawl Are you going in or what?

Inside there were probably no more than five drunks. It was hard to tell for sure, because there was often one facedown in the sawdust. The place smelled, as it should, of piss and fermented fruit. In the back, a curtain separated the scum from the VIPs: though it was just a piece of cloth, no one entered the inner sanctum without permission. I don’t have all day, Makina heard Mr. Aitch say.

She pulled the curtain aside and behind it found the bird-print shirt and glimmering gold that was Mr. Aitch playing dominoes with three of his thugs. His thugs all looked alike and none had a name as far as she knew, but not one lacked a gat. Thug .45 was on Mr. Aitch’s side playing against the two Thugs .38. Mr. Aitch had three dominoes in his hand and glanced sidelong at Makina without setting them down. He wasn’t going to invite her to sit.

You told my brother where to go to settle some business, said Makina. Now I’m off to find him.

Mr. Aitch clenched a fist around the bones and stared straight at her.

You gonna cross? he asked eagerly, though the answer was obvious. Makina said Yes.

Mr. Aitch smiled, sinister, with all the artlessness of a snake disguised as a man coiling around your legs. He shouted something in a tongue Makina didn’t speak, and when the barman poked his head around the curtain said Some pulque for the young lady.

The barman’s head disappeared and Mr. Aitch said Of course, young lady, of course … You’re asking for my help, aren’t you? Too proud to spell it out but you’re asking me for help and I, look at me, I’m saying

Of course

.

Here came the hustle. Mr. Aitch was the type who couldn’t see a mule without wanting a ride. Mr. Aitch smiled and smiled, but he was still a reptile in pants. Who knew what the deal was with this heavy and her mother. She knew they weren’t speaking, but put it down to his top-dog hubris. Someone had spread that he and Cora were related, someone else that they had a hatchet to bury, though she’d never asked, because if Cora hadn’t told her it was for a reason. But Makina could smell the evil in the air. Here came the hustle.

All I ask is that you deliver something for me, an itty bitty little thing, you just give it to a compadre and he’ll be the one who tells you how to find your kin.

Mr. Aitch leaned over toward one of the .38 thugs and said something in his ear. The thug got up and versed from the VIP zone.

The barman reappeared with a dandy full of pulque.

I want pecan pulque, Makina said, and I want it cold, take this frothy shit away.

Perhaps she’d gone too far, but some insolence was called for. The barman looked at Mr. Aitch, who nodded, and he went off to get her a fresh cup.

The thug returned with a small packet wrapped in gold cloth, tiny really, just big enough to hold a couple of tamales, and gave it to Mr. Aitch, who took it in both hands.

Just one simple little thing I’m asking you to do, no call to turn chicken, eh?

Makina nodded and took hold of the packet, but Mr. Aitch didn’t let go.

Knock back your pulque, he said, pointing to the barman who’d reappeared, glass at the ready. Makina slowly reached out a hand, drank the pecan pulque down to the dregs and felt its sweet earthiness gurgle in her guts.

Cheers, said Mr. Aitch. Only then did he let the bundle go.

You don’t lift other people’s petticoats.

You don’t stop to wonder about other people’s business.

You don’t decide which messages to deliver and which to let rot.

You are the door, not the one who walks through it.

Those were the rules Makina abided by and that was why she was respected in the Village. She ran the switchboard with the only phone for miles and miles around. It rang, she answered, they asked for so and so, she said I’ll go get them, call back in a bit and your person will pick up, or I’ll tell you what time you can find them. Sometimes they called from nearby villages and she answered them in native tongue or latin tongue. Sometimes, more and more these days, they called from the North; these were the ones who’d often already forgotten the local lingo, so she responded to them in their own new tongue. Makina spoke all three, and knew how to keep quiet in all three, too.

The last of the top dogs had a restaurant called Casino that only opened at night and the rest of the day was kept clear so the owner, Mr. Q, could read the papers alone at a table in the dining room, which had high ceilings, tall mullioned windows and gleaming floorboards. With Mr. Q Makina had her own backstory: two years before she’d worked as a messenger during emergency negotiations he and Mr. Aitch held to divvy up the mayoral candidates when their supporters were on the verge of hacking one another to pieces. Midnight messages to a jittery joe who had no hand in the backroom brokering and suddenly, on hearing the words Makina relayed (which she didn’t understand, even if she understood), decided to pull out. An envelope slipped to a small-town cacique who went from reticent to diligent after a glance at the contents. Through her, the top dogs assured surrender here and sweet setups there, no bones about it; thus everything was resolved with discreet efficiency.

Mr. Q never resorted to violence—at least there was nobody who’d say he did—and he’d certainly never been heard to raise his voice. Anyhow, Makina had neither been naive nor lost any sleep blaming herself for the invention of politics; carrying messages was her way of having a hand in the world.

Casino was on a second floor, and the door downstairs was unguarded; why bother: who would dare? But Makina had no time to ask for an appointment and anyone who knew her knew she wasn’t one to put people out for the sake of it. She’d already arranged for her crossing and how to find her brother, now she had to make sure there would be someone to help her back; she didn’t want to stay there, nor have to endure what had happened to a friend who stayed away too long, maybe a day too long or an hour too long, at any rate long enough too long that when he came back it turned out that everything was still the same, but now somehow all different, or everything was similar but not the same: his mother was no longer his mother, his brothers and sisters were no longer his brothers and sisters, they were people with difficult names and improbable mannerisms, as if they’d been copied off an original that no longer existed; even the air, he said, warmed his chest in a different way.

She walked up the stairs, through the mirrored hall and into the room. Mr. Q was dressed, as usual, in black from neck to toe; there were two fans behind him and on the table a national paper, open to the politics. Beside it, a perfect white cup of black coffee. Mr. Q looked her in the eye as soon as Makina versed the mirrored hall, as if he’d been waiting for her, and when she stood before him he made a millimetric move with his head that meant Sit. A few seconds later, without being told, a smocked waiter approached with a cup of coffee for her.

I’m going to the Big Chilango, Makina said; no bush-beating for Mr. Q, no lengthy preambles or kowtows here: even if it seemed that skimming the news was downtime, that was where his world was at work; and she added On a bus, to take care of some family business.

You’re going to cross, said Mr. Q. It wasn’t a question. Of course not. Forget trying to figure out how he’d heard about it so fast.

You’re going to cross, Mr. Q repeated, and this time it sounded like an order. You’re going to cross and you’re going to get your feet wet and you’re going to be up against real roughnecks; you’ll get desperate, of course, but you’ll see wonders and in the end you’ll find your brother, and even if you’re sad, you’ll wind up where you need to be. Once you arrive, there will be people to take care of everything you require.