Signor Marconi's Magic Box (11 page)

Read Signor Marconi's Magic Box Online

Authors: Gavin Weightman

Marconi paid regular visits, but spent most of his time conducting experiments at the Haven Hotel. His mother still fussed about his clothes, even when she was away in London or Ireland or Italy. From Bologna she sent him a letter at about this time: ‘I am thinking if it has got warmer at the Haven Hotel you will want your lighter flannels. Mrs Woodward has the keys of your boxes. Your flannels are in the box with the two trays. Summer sleeping-suits on the first tray. Summer shirts under the two trays. Summer suits, jackets, waistcoat and trousers in the wardrobe.’

Early in January 1901 a London newspaper, the

Illustrated Mail

, sent a reporter down to the Haven Hotel to find out what was going on, and published a full-page feature entitled ‘A Chat with Mr Marconi’. It began:

Illustrated Mail

, sent a reporter down to the Haven Hotel to find out what was going on, and published a full-page feature entitled ‘A Chat with Mr Marconi’. It began:

Though bearing a purely Italian name, there is nothing of the foreigner in Mr Marconi’s appearance. His speech is that of an educated scientific Englishman and his dress and general manner are those of a pleasant young English gentleman. One understands this when one sees Mr Marconi’s mother, who is an English lady, and generally lives with him at Poole harbour. Mr Marconi, of course, finds it necessary to make occasional visits to London, but

with these exceptions and a daily run of an hour or so on his bicycle, all his working hours are devoted to the study of his inventions. Wireless telegraphy has passed out of the sphere of experiment and become an established fact, and Marconi’s efforts are now dedicated to the working out of details, the perfecting of the apparatus, and the lengthening of the distance over which electric communication can be effectively worked.

with these exceptions and a daily run of an hour or so on his bicycle, all his working hours are devoted to the study of his inventions. Wireless telegraphy has passed out of the sphere of experiment and become an established fact, and Marconi’s efforts are now dedicated to the working out of details, the perfecting of the apparatus, and the lengthening of the distance over which electric communication can be effectively worked.

‘What distance can you negotiate now?’ asked the

Illustrated Mail

representative.

Illustrated Mail

representative.

‘One hundred miles - or perhaps a bit more - have been successfully worked, and you may take it for granted that in a very short time this distance will be doubled, and even quadrupled,’ replied Mr Marconi.

‘Is there any truth in reports that you are contemplating the sending of messages between this country and America?’

‘Not in the least. I have never suggested such an idea, and though the feat may be accomplished some day, it has as yet hardly been thought of here.’

Marconi was apologetic about the untidiness of the rooms in which he was working, strewn with coils and batteries and lengths of wire: ‘This is not by any means a show place. We have no time to spend on beautiful instruments and decorations. We have made hundreds of experiments here, and you will readily understand that there has been no time to waste.’ The reporter did not enquire why Marconi was in such a hurry; as far as the readership of the

Illustrated Mail

knew, Marconi had no real rivals. Marconi, however, was acutely aware that there were a great many problems to be solved, and that there were contenders who could overtake him. Though he concealed the real purpose of the Poldhu station from the

Illustrated Mail

reporter, Marconi’s ambition was in fact to be the first to send a wireless signal across the Atlantic.

Illustrated Mail

knew, Marconi had no real rivals. Marconi, however, was acutely aware that there were a great many problems to be solved, and that there were contenders who could overtake him. Though he concealed the real purpose of the Poldhu station from the

Illustrated Mail

reporter, Marconi’s ambition was in fact to be the first to send a wireless signal across the Atlantic.

In Germany, Professor Adolphus Slaby had teamed up with

another scientist, Count von Arco, and was publicising his field wireless telegraphy system as a useful addition to army signals. And word was reaching Marconi of a Professor Fessenden in America who had had some success in sending wireless messages over short distances. In Russia there was Alexander Popov, who had built a receiver which picked up at a distance the electro-magnetic waves from lightning bolts, and could forecast the arrival of thunderstorms. Like Oliver Lodge in England, Popov had sent a wireless signal over six hundred yards, for which he had received a Gold Medal at the 1900 Paris Exhibition. In France an instrument-maker, Eugène Ducretet, had built his own version of wireless telegraphy equipment, and as early as 1898 had sent a message from the Eiffel Tower across Paris to the roof of the Pantheon. For all Marconi knew there were others at work who might beat him to the breakthrough he hoped for.

another scientist, Count von Arco, and was publicising his field wireless telegraphy system as a useful addition to army signals. And word was reaching Marconi of a Professor Fessenden in America who had had some success in sending wireless messages over short distances. In Russia there was Alexander Popov, who had built a receiver which picked up at a distance the electro-magnetic waves from lightning bolts, and could forecast the arrival of thunderstorms. Like Oliver Lodge in England, Popov had sent a wireless signal over six hundred yards, for which he had received a Gold Medal at the 1900 Paris Exhibition. In France an instrument-maker, Eugène Ducretet, had built his own version of wireless telegraphy equipment, and as early as 1898 had sent a message from the Eiffel Tower across Paris to the roof of the Pantheon. For all Marconi knew there were others at work who might beat him to the breakthrough he hoped for.

While he concentrated on building a transmitter that would send a signal further than anybody thought possible, Marconi was grappling with another problem: tuning. A wireless signal sent from a spark transmitter could be picked up by anyone who had a receiver. There was no privacy for the sender, no way of narrowing down the signal to a particular wavelength which could only be picked up by a receiver ‘tuned in’ to it. It was understood that wireless waves varied greatly in length - the distance between the crests of the waves - and that a receiver needed to be tuned to roughly the same wavelength as a transmitter for a signal to be picked up. There was therefore the possibility of dividing up the ‘ether’ into different wavebands which would not interfere with each other. In 1900 Marconi believed he had got far enough with a solution to this problem to take out a patent which had the number 7777 - known from then on as the ‘four sevens patent’. But in reality he and his engineers had only a vague idea what wavelength they were on at any time, for they had no way of measuring the crests between the waves sent out by their transmitters. And even ‘tuned’ signals were not private, as anyone with adjustable receiving equipment could fish about until they picked

up a signal that was not intended for them. This did not matter to passenger liners at sea, which simply wanted to be able to telegraph each other, and harboured no secrets. But for armies and navies, potentially the most important customers for wireless, it was obviously a stumbling block. If the enemy could tap your messages, wireless was likely to be a hazard rather than a help. And even in peacetime there was the problem that if everyone was on more or less the same wavelength, their signals would continually interfere with each other.

up a signal that was not intended for them. This did not matter to passenger liners at sea, which simply wanted to be able to telegraph each other, and harboured no secrets. But for armies and navies, potentially the most important customers for wireless, it was obviously a stumbling block. If the enemy could tap your messages, wireless was likely to be a hazard rather than a help. And even in peacetime there was the problem that if everyone was on more or less the same wavelength, their signals would continually interfere with each other.

For the time being, though, there were few wireless stations in the world, and they were so far from each other that there was no question of eavesdropping or interference. The Marconi companies had most of them in 1900, and they were the only wireless pioneers who had gone in for the manufacture of equipment. The first factory of its kind in the world had been set up in an old silk warehouse in Chelmsford, Essex, to the east of London in 1898, and a workforce, chiefly of women, turned out the spark transmitters and glass tube coherer receivers in anticipation of orders from the British Navy and shipping lines. A huge German liner, the

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse

, was the first ship to be fitted with Marconi wireless, W.W. Bradfield, ‘editor in chief’ of the

Transatlantic Times

, supervising the work. The liner exchanged messages with stations on Borkum Riff lightship and Borkum lighthouse in north Germany.

Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse

, was the first ship to be fitted with Marconi wireless, W.W. Bradfield, ‘editor in chief’ of the

Transatlantic Times

, supervising the work. The liner exchanged messages with stations on Borkum Riff lightship and Borkum lighthouse in north Germany.

Two companies with Marconi’s name were now in business: the original Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company, which now had ‘Marconi’ tagged on, and the Marconi International Marine Company, formed with international capital in 1900, but neither was as yet making any money. An infant industry had been founded, and there were just enough customers for wireless to keep it ticking over. Marconi put little store in the achievements he had already made. In 1901 he was determined to put nearly all his energy and the very large sum of £50,000 of company money into his attempt to span the Atlantic. He kept quiet about it because he did not want to damage his credibility by making predictions that would

embarrass him if he failed. The distinguished Professor of Electrical Engineering at University College London, Ambrose Fleming, was taken on as a consultant at £500 a year. It was his job to design and test the generator that would be housed in the transmitter building that had been put up next to the Poldhu Hotel in Cornwall. The task of erecting a series of wooden masts around the building to carry a giant spider’s web of an aerial was given to the loyal George Kemp, who hired local men and horses for the heavy work that had to be done.

embarrass him if he failed. The distinguished Professor of Electrical Engineering at University College London, Ambrose Fleming, was taken on as a consultant at £500 a year. It was his job to design and test the generator that would be housed in the transmitter building that had been put up next to the Poldhu Hotel in Cornwall. The task of erecting a series of wooden masts around the building to carry a giant spider’s web of an aerial was given to the loyal George Kemp, who hired local men and horses for the heavy work that had to be done.

Marconi had been poring over maps of the eastern seaboard of America in search of a place to build a replica of the Poldhu transmitter, and had stuck his pin into Cape Cod. He wanted somewhere which had a clear run of sea to the Poldhu cliff, and the more remote it was, the better: he did not want prying eyes to see the masts going up, or the powerful currents that would be generated to attract attention by interfering with nearby electrical installations. At the beginning of February Marconi left Fleming and Kemp to get on with the Poldhu work, and took with him across the Atlantic Richard Vyvyan, who would supervise the building of the American station. Vyvyan went reluctantly, for he had told Marconi and the company in London that the huge aerials they intended to put up were structurally unsound, and would be vulnerable to high winds. Though Marconi had no engineering expertise, Vyvyan was overruled and ordered to toe the line.

Cape Cod proved to be much wilder than the Lizard peninsula in Cornwall. Marconi did not have the contacts here that he had in England, which made it difficult for him to find a site for his station. In the end, help came from the kind of man he would not normally have had any dealings with, a native of Cape Cod called Ed Cook, who made his living as a ‘wrecker’. The busy sea lane into Boston harbour was treacherous and every year ships were driven aground and broken up. On Cape Cod, as elsewhere on the wilder coasts, there were scavengers who searched for cargo washed ashore, and looted the corpses of the drowned. Newspapers still carried shocking reports of wreckers who ignored the cries for help

of those drowning just offshore so that there would be plunder for their grim harvest.

of those drowning just offshore so that there would be plunder for their grim harvest.

The ill-matched pair, Cook in rugged clothing and Marconi in a fur coat - the weather was bitterly cold - explored the coast in a horse and cart. The most suitable site was already occupied by the Highland Light semaphore station, which recorded the passing of ships and cabled news of their arrival to their owners in Boston and New York. The operators working there would not allow Marconi on the site, and he had to settle instead for a clifftop above a bay, where the heavy equipment could be landed by sea and which had a hotel nearby. This was the South Wellfleet, and its hospitality fell well short of that provided by the Haven

.

After a taste of the local food Marconi refused to try it again, having supplies sent from Boston. He did not stay long at South Wellfleet, and left Richard Vyvyan to organise the delivery of pine posts and all the other equipment needed to build what was then the second-largest wireless station in the world, designed to be almost as powerful as Poldhu. In theory it should be able to send signals the 2300 miles across the Atlantic to Poldhu in Cornwall.

.

After a taste of the local food Marconi refused to try it again, having supplies sent from Boston. He did not stay long at South Wellfleet, and left Richard Vyvyan to organise the delivery of pine posts and all the other equipment needed to build what was then the second-largest wireless station in the world, designed to be almost as powerful as Poldhu. In theory it should be able to send signals the 2300 miles across the Atlantic to Poldhu in Cornwall.

Back at Poldhu, George Kemp was struggling to keep the ring of aerial masts upright as spring and then summer winds frustrated his efforts. Gusts continuously tore away bits of the structure, and Kemp had to search for new sources of timber. On one occasion he went with the coastguards to retrieve the mast of a wrecked ship, and incorporated it into the Poldhu aerial. All the time the generator and power plants devised by Professor Fleming were being tested, sometimes with unexpectedly violent results. Kemp noted in his diary on 9 August 1901: ‘We had an electric phenomenon - it was like a terrific clap of thunder over the top of the masts when every stay sparked to earth in spite of the insulated breaks. This caused the horses to stampede and the men to leave the ten acre enclosure in great haste.’ For want of any other terminology to describe the unique structure he was working on, Kemp, an ex-naval officer, referred to the various masts and spurs as ‘top gallant stays’ and ‘triatic’ stays, for all the world as if he were planning to launch this piece of cliff across the Atlantic. Marconi was experimenting with different amounts of power and windings of coil, in search of the most effective arrangement for sending signals long distances. Bit by bit the Poldhu station began to exchange signals with stations sited eastwards along the coast, sometimes with naval stations which had bought Marconi equipment, and sometimes with a Marconi station which had been set up at Crookhaven at the south-western tip of Ireland.

Guglielmo Marconi shortly after his arrival in London in 1896. The portrait captures his calm, serious manner, which belied his youth - he was just twenty-two. He described himself as ‘an ardent student of electricity’.

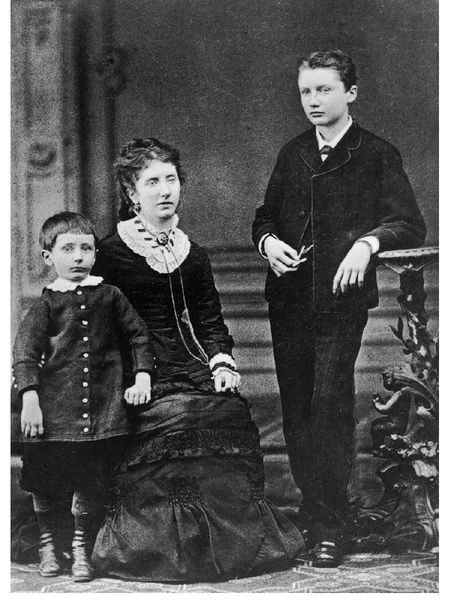

Marconi, aged about four, with his mother Annie Jameson of the Irish whiskey family and his brother Alfonso at their home, the Villa Griffone near Bologna in Italy.

Other books

Fall of Lucifer by Wendy Alec

The Horror in the Museum by H. P. Lovecraft

The Work and the Glory by Gerald N. Lund

Embrace the Night by Roane, Caris

Infinite Ties (All That Remains #3) by S. M. Shade

SVH05-All Night Long by Francine Pascal

Chameleon by William Diehl

Confessions of a Serial Kisser by Wendelin Van Draanen

Mr. February by Ann Roth