Ship Captain's Daughter (7 page)

Read Ship Captain's Daughter Online

Authors: Ann Michler Lewis

The company's “china” featured a red, white, and blue flag with the initials PM in the middle, standing for the company's founders, Colonel James Pickands and Samuel Mather. Even when the company merged with another to become The Interlake Steamship Company, the fleet continued to be known to its employees as the PM Line.

The fog began to roll in, and soon the throaty ship whistle started sounding our position every two minutes. Several other ships in the distance began to do the same. Over the whistles, I could hear Dad's contented snoring. I lay in bed watching my sweatshirt on the wall hook sway back and forth to the rhythm

of the rocking of the ship. Two and a half days down, and two and a half days up. I wondered what my friends were doing. I wondered if they thought about me. I wondered if somebody had ridden his bike by my house. I fell asleep, dreaming of sailing in the South Seas with a handsome lover.

When we started to see the North Shore again on our return trip, I put my hot rollers in, getting ready to disembark in Duluth. Dad was getting ready, too, to enter the port.

“Want to come up to the pilothouse with me?” he asked, sticking his head in the bedroom door. “But you'll have to take out those whatchamacallits!”

He stood there chuckling. I could tell he really wanted me to come up with him. After all, I thought, we would have only a few more hours together, so I took them all out. I put the bobby pins back in the jar, stuck my hair in a ponytail, and went up.

It was still open water. Dad didn't have to be “in the window” quite yet, so he told the second mate to stay there, and he went back to the big desk and got the chart out of the drawer. He showed me Two Harbors off to our right. We had passed the Apostle Islands several hours before, but he pointed them out on the chart, knowing that I had been there. He told me about the time he had taken coal to Washburn and then sailed out to Duluth between Bayfield and Basswood and Oak Islands, and how tricky it was because of the currents and shoals.

Then he closed the drawer, walked up to the window to relieve the mate, looked back at me, and said, “I think you should give the wheelsman a break and take a try at the wheel. I was thinking you should do some wheeling this trip, and here we are already at the end of it.”

I thought he was kidding, but the wheelsman smiled and said, “Here you go, matey.” He stepped off the little platform, looked at me, and said, “Steering steady as she goes.”

Dad said, “Go ahead.” When the wheelsman went over to

the thermos and started to pour some coffee, I could see that this was serious. I stepped up on the platform, and Dad said, “Now put your hands on ten and two of an imaginary clock and take hold of the spokes of the wheel in those places.” The big wooden wheel was still warm from the wheelsman's hands, smooth and smelling like furniture polish.

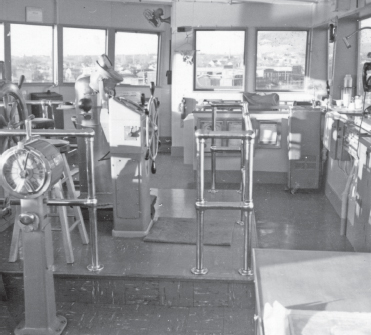

The wheel in the pilothouse stood on a platform, elevating the wheelsman so he could see out of the surrounding windows.

“The trick to wheeling is that you have to anticipate the rate at which the ship responds,” Dad said. “You have to get a sense of how long you have to keep the wheel over before it catches. If you hold it over too long one way or the other, the ship turns back and forth too much. Then you're always overcorrecting it, and it will zigzag. Every ship handles differently, so a good wheelsman learns how long it takes for the rudder to respond

on the particular ship he's wheeling. In open water, what you're aiming for is to keep a straight wake.

Mother takes the wheel with her hair up in pin curls under her bandanna, which would come off for dinner at the captain's table. The humidity, she lamented, often caused her hair to go flat.

“Now look down in front of you and you'll see the compass. When you turn the wheel and the ship moves, it will look like the compass is moving the opposite way of the ship. That's because the ship moves around the compass. You have to get used to that. When I say, âSteady as she goes,' you want to keep the lubbers line on the compass from moving either way.”

“Do you ever take the wheel?” I asked. “Like if the wheelsman isn't doing it right?”

“Nope, I don't. By the time you're wheeling a ship like this, you know what you're doing. My job is to analyze and chart the course. The wheelsman's job is to get the ship to do it. Your mother's done it! So let's practice.”

He continued, “Take a half-turn to starboard and wait and see how long before the ship grabs hold so you can get an idea of what it feels like.”

I turned the wheel several spokes to the right and nothing happened, so I turned it some more.

“Remember,” Dad said, “it takes a while for the ship to answer you. The wheel shaft is about a block long, so just be patient. Another thing, when I give an order, you repeat it. That's an international sailing law to make sure that the captain knows that the wheelsman has heard exactly what the captain wants.”

“Aye, aye, sir!” I said.

Then he repeated, “Take it one-half turn to the right,” and I said, “One-half turn to the right,” and in about a minute, it started to turn, a lot. I panicked and quickly turned the wheel the opposite direction to get it to come back. A long minute later, it started to go left, but then it went a little too far. It felt scary, and I wondered out loud what the men on deck were thinking with the ship, all of a sudden, waltzing back and forth.

The wheelsman laughed. I turned the wheel back the other way.

“Check your wake,” Dad said. I looked back, and it looked like a Z. “Now you can see how that works. You have to make smaller adjustments. Just let the wheel go now and get itself back to midships and then keep her steady as she goes.”

“Back to midships,” I said, and I let the wheel go. It went back by itself to the middle, again.

“Remember, just small adjustments are enough to keep her going straight. Think of yourself as helping the ship find its path. You really have to feel her, how she likes to move. Every ship is different. See that ship in the distance? Keep the steering pole right on it.”

“Aye, aye, captain,” I said. “Steering pole on the ship.”

“Attagirl,” he said.

I kept a pretty straight wake until a little land breeze came up. Then it began to get wavy, and we started to slip off course as the wheel got harder and harder to hold onto. Dad didn't say

anything, but the real wheelsman could see I was struggling. After a few minutes, he got up and stood a few steps behind me.

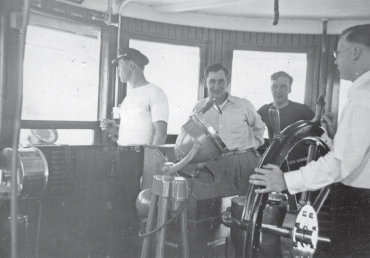

In the pilothouse, Dad, left, is pictured with the mate, the watchman, and the wheelsman, who had just come on duty for his four-hour shift.

He kept hovering there, and then he finally said, “What do you think, Cap?”

Dad said, “It's okay, Charlie, let her keep trying. You have to learn how to handle a little chop.” I stuck it out for a while longer, and then the wind got stronger, and the waves started to pound harder. The Aerial Bridge at Duluth was starting to come into view, and there were several ships at anchor, and one coming toward us.

The wheelsman cleared his throat, and then he said again, “What do you think, Cap?”

Finally, Dad said, “Okay, Charlie, keep her on the bridge.”

Charlie said, “On the bridge, sir.” As he stepped up, I stepped down.

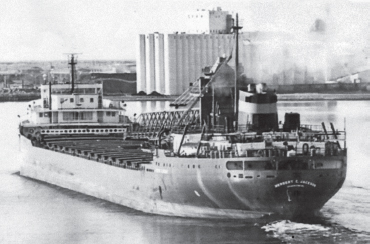

After passing through Duluth's Aerial Bridge, the SS

Herbert C. Jackson

makes a left turn toward a dock just past the grain elevators across the bay in Superior, Wisconsin.

DIANE HILDEN

I stayed around for a little while. I had a donut and played with the slide rule on the chart desk, and then I asked if it was okay if I went back down. Dad didn't answer, as just then the phone rang and he started talking to the captain of the ship we had been following. It was just starting to enter the canal. He told Dad there was a strong current running out of the bay today. There was a “saltie” just letting go of its lines over at the grain dock, the man said, and it would probably meet us at the turn by Rice's Point right after we got through the canal.

Dad thanked him for the heads-up, lit a cigarette, blew for the bridge, and then he looked down. At the entrance to the canal, Mom was waving on the walkway in front of the lighthouse. Dad blew her the captain's salute, one long blast and two short ones, then grabbed the big bullhorn, shot out the door, and yelled, “Forty minutes to the dock!” as we passed her.

I ran out too and waved at Mom and all the people gathered

to watch what always felt like a triumphal entry. Dad had already dashed back and started to call for a tug, seeing that there was both current and traffic.