Sheer Gall (24 page)

Authors: Michael A Kahn

I knocked.

“Rachel?” Amy called.

“It's me.”

“Door's open.”

I turned the handle and stepped into the reception area of what had once been Sally Wade & Associates. Amy was seated on the carpet, her back propped against the front of the receptionist's desk. She was wearing a Chicago Bears jersey, faded jeans, and tennis shoes, and she was surrounded by storage boxes. Literally. Boxes on the floor, boxes on the reception desk, boxes on the couch. She had an open box on the carpet between her legs.

“Oy,” I said.

Amy uttered an exhausted sigh. “Believe me, this is one job I definitely will not miss.”

I looked around. “Wow. I had no idea she had so many Douglas Beef files.”

“Hah,” Amy snorted. “I had no idea she was so disorganized back then. Every one of these boxes is a mishmash of files. From what I can tell, she'd wait until she had a box worth of closed files and then ship them off to storage. Take this one,” she said, gesturing at the box in front of her. She pulled out a file folder and opened it. “What do we have here? Ah, yes, a personal injury case. Auto accident. Settled for, let's see, four grand.”

She stuffed the file back in the box and pulled out another. “Let's seeâ¦this looks like a slip-and-fall. In a National supermarket.” She put that one back and started paging slowly through the rest of the folders in the box. “Here we've got a medical-mal caseâ¦followed by, let's see, another fender-bender. Both closed in August six years ago. Same as the others in the box.” She flipped through two more files. “Ah, here we go. Finally.” She pulled out a folder and held it up triumphantly.

“Douglas Beef?” I asked.

“Yep.” She studied the label on the file. “Workers' comp claim.” She opened the folder on her lap and started leafing through the pages. “What do we have here? Mmm-hmm. Mmm-hmm. Oh, my. Bad times on the loading dock. Looks like someone backed over poor Howie Goodman's left foot with a forklift.” She looked up at me and uttered an exaggerated groan. “Explain this again. What am I supposed to be looking for?”

“A needle in a haystack. More precisely, a gallstone in a haystack.”

She looked perplexed. “Why just the older Douglas Beef files?”

“According to Sally's passport,” I explained, “she made her first trip to Hong Kong four years ago. Assuming she went over there to sell cattle gallstones, she must have made her contact at Douglas Beef before then. There might be a clue in one of the older files.”

She nodded. “Makes sense.”

I set my purse and briefcase onto the floor and walked over to the couch. “I'll help.” I sat down next to a box.

When we called it quits three hours later, I was in a state of total information overload. Between us, we'd found eighteen Douglas Beef filesâall workers' comp claimsâand we still had half the boxes to go. The files we'd found consisted of dozens and dozens of pages of seemingly irrelevant material. Brady Kane had been a witness in a few of the cases, but there was no indication of any direct contact between him and Sally. Nor was there mention in any of the files of gallstones, organ sales, Hong Kong, or anything remotely connected to the criminal case of

People of the State of Missouri v. Neville McBride

.

When I returned to my office around two o'clock, there was a manila envelope from Tully, Crane & Leonard waiting for me. The envelope contained a handwritten note from Neville McBride paperclipped to two pages photocopied from the firm's Client/Matter Report and two from the firm's Closed File Log.

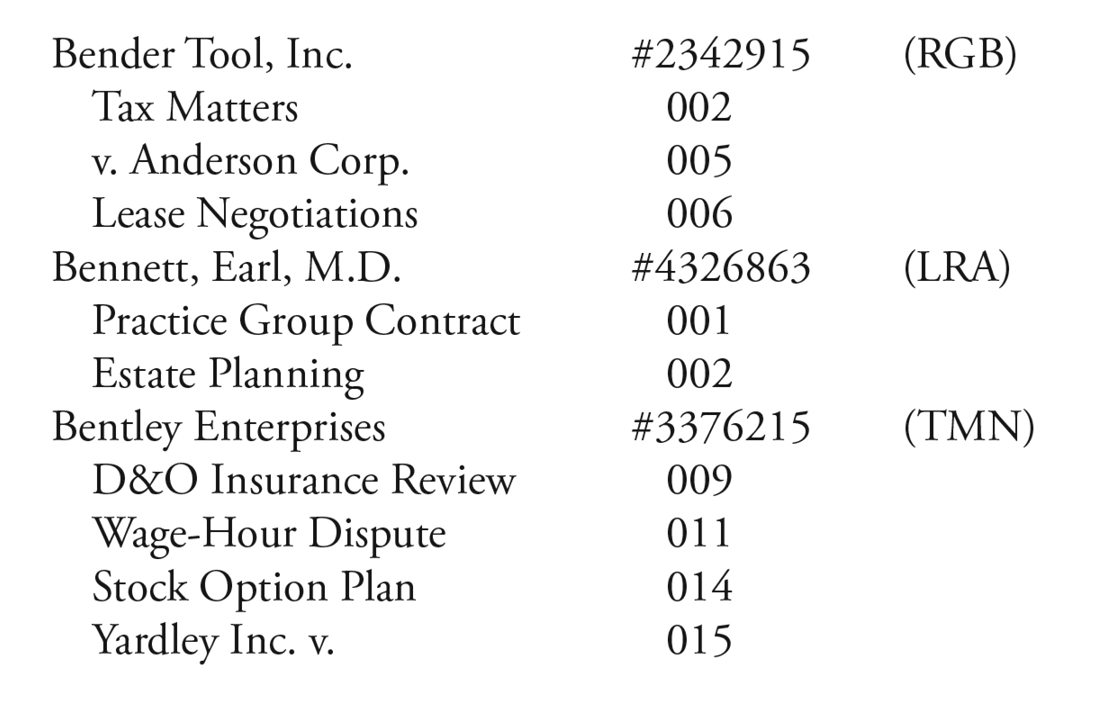

The Client/Matter Report was arranged alphabetically by client, with separate matters listed beneath each client and the initials of the billing attorney shown at the far right. The first of the two pages of the report were from the B's and had been copied, according to Neville McBride's handwritten note, to show that Bennett Industries (parent company of Douglas Beef) was not currently a client of the firm:

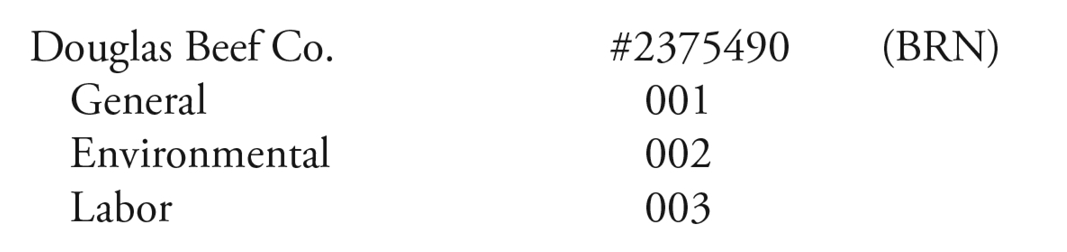

The second page from the Client/Matter List was from the D's. Neville had highlighted the entries for Douglas Beef:

The document showed three current matters for Douglas Beef, all identified in the most generic possible way. The BRN stood for Bruce R. Napoli, which meant he was the partner in charge of the client.

The second two pages in the packet had been copied from the Closed File Log. The first page showed two matters for Bennett Industriesâ“Opinion Letter re Drabble” and “Missouri Franchise Tax re Drabble.” Both had been closed for more than five years. The initials of the billing attorney were HLD (Harrison L. Dawber, according to my Tully, Crane telephone directory). Neville McBride had scribbled in the margin: “Spoke to Harry re Bennettâsays our firm retained for limited purposes re sale of Drabble Plastiform Co. to Condesco Inc.âHarry and 1 associate did all work on both matters.” The second photocopied page was from the D's and showed that there were no closed matters for Douglas Beef.

I called McBride. “Can you get a billing and collections report on Douglas Beef?” I asked.

“I have it in front of me.”

“What's it show?”

“Year to date, we've billed Douglas Beef $56,750. Last year, we billed them $83,500. The year before, $64,355.”

“What are Bruce's origination numbers?”

“Just a moment.” I heard him rustling through papers.

Law firms track various numbers for each partner: hours billed, realization rate on those hours, and the like. But for a rainmaker like Bruce Napoli, the most important numbers are the origination numbers, which represent the dollars his clients pay the firm for services rendered. The bigger the origination numbers, the larger the compensation and the greater the power.

“Here we go. Year to date, Bruce has three point eight million dollars. Last year, four point five million dollars. The year before three point nine.”

I jotted the numbers down. Douglas Beef was not a significant client of his, at least from a dollars angle.

I rapped the eraser end of my pencil on the legal pad as I studied the photocopied materials. “Tell me about your computer system.”

He chortled. “You are asking the wrong person, Rachel. My level of expertise in modern office technology extends no further than my portable dictation machine, which I started using for the first time this summer when my secretary was on vacation and the temp didn't know shorthand.”

“Are your computers networked?”

“Yes, although I'm not quite sure what it means other than that people can send e-mail messages to each other. I get the damn things all day long.”

“The firm has a D.C. office, right?”

“Indeed we do. We also have offices in Orlando and West Palm Beach.”

“I assume all of your offices are on the network?”

“Oh, yes. That was a big selling point for the system.”

I smiled. “Excellent.”

“Really?”

“Trust me.”

I said good-bye and placed a call to Henderson Consulting in Chicago.

“Mr. Henderson, please,” I told the breathy receptionist.

Next to answer was his secretary, sounding even more sensual than the receptionist.

I had to smile. “Can I talk to him?” I asked.

“For whom shall I tell Mr. Henderson is calling?”

I paused long enough to decide her sentence didn't parse. “Tell him it's Rachel Gold.”

“Just a moment, Ms. Gold.”

Another delay, and then a familiar voice. “Yo, Rachel. What's up, girl?”

“Who you calling âgirl,' Ty? That's âwoman' to you.”

“I'll call you woman, girl, when you finally acknowledge reality and become

my

woman.”

“You know the rules, Ty. Mom says it has to be a nice Jewish boy. Until you join

my

religion, I can't become

your

woman.”

“Hey, baby, you ain't talking to no Sammy Davis, Jr.”

“And you ain't talking to no honky bimbo. Speaking of which, Mr. Henderson, who is that phone sex brigade answering your phones?”

“Ain't they something? Those girls give good phone, and don't my clients love it, heh, heh.”

Tyrone Henderson was one of my favorite people, and his success over the years had been marvelous to observe. We had joined Abbott & Windsor the same year: he fresh out of high school as a minimum-wage messenger, I fresh out of Harvard Law School as a litigation associate at the going rate back then of forty-eight thousand a year plus bonus. Tyrone spent his days delivering draft contracts and court papers to other firms in the Loop and his nights taking courses in computer programming. When he earned his certificate from night school, he applied for an opening on the firm's

In re Bottles & Cans

computer team. By the time I left the firm, Tyrone was the head programmer for the national

Bottles & Cans

defense steering committee. Over the years he helped design many of Abbott & Windsor's computer systems, including the network linkup with all of its branch offices. Two years before, he'd left Abbott & Windsor to start his own consulting firm specializing in the design of computer systems for law firms.

“By the way,” I said, “I finally got your picture framed.”

“About time, girl.”

Last winter, Tyrone had been featured in a

Chicago

magazine piece on the city's most eligible bachelors. I'd picked up a copy of the issue, cut out the page with his photograph, and sent it to him for an autograph. He sent it back, signed:

To Rachel, We'll always have Paris. Ty

.

“But I'm having a problem with the glare, Ty.”

“What glare?”

“Off your shaved head. That thing is shinier than an eight ball. What did you do, Ty, have them buff it before the shot?”

He chuckled. “Drives the ladies wild. So what's up, girl?”

“I need a computer consultant.”

“You dialed the right number.”

I described the situation to him.

“I see,” he said, his voice instantly becoming utterly professional. Tyrone Henderson could downshift from Cabrini-Green rap to corporate consultant diction and back up again in a nanosecond. “I take it that access to the files themselves is not a viable option.”

“Definitely,” I said. “I'd have to go through his niece, and that would get right back to him.”

“So we talkin' âbout a little breakin' and enterin'?”

“Well, yes. If there was a way to get into the firm's computer network without being physically present at a terminal in their offices, I could look through the Douglas Beef documents in the system without anyone knowing about it. Can that be done?”

“Easier than you'd imagine. I spend half my time preaching computer security to managing partners. Most law firms have almost no protection. If that firm is typical, I'll be able to get you in.”

“My hero.”

“Ain't that the truth. Now here's what you need to do. You call over there pretending that you're some lawyer's secretary from, say, Detroit, and ask to talk to someone in their systems department. Tell them that you're supposed to modem a document over there next week and you need some information about their system.”

Tyrone proceeded to run through a list of questions for me to ask. He also gave me reasonable answers to questions that the Tully, Crane systems person might ask me. I wrote them down word for word, since I understood less than half of what he told me.

His strategy worked. I got the information he needed, and the systems person at Tully, Crane actually asked me two of the questions Tyrone had prepared me to answer. I called him back and passed on the information. He called me back an hour later with my instructions.

“You call me, Rachel, if you have problems.”

“Okay.”

“You'll need a password to get in those files or to read old e-mail messages. Here's the one I assigned to you.” He read off seven numbers. “Got that?”