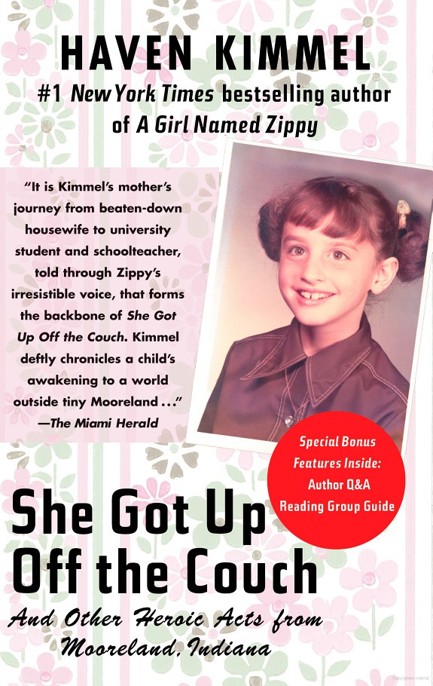

She Got Up Off the Couch

Read She Got Up Off the Couch Online

Authors: Haven Kimmel

A Girl Named Zippy

The Solace of Leaving Early

Orville:A Dog Story

Something Rising (Light and Swift)

FREE PRESS

FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2006 by Svarakimmel Industries, LLC

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

FREE PRESS

and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Designed by Karolina Harris

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kimmel, Haven.

She got up off the couch : and other heroic acts from Mooreland, Indiana. / Haven Kimmel.

p. cm.

1. Kimmel, Haven — Family. 2. Kimmel, Haven — Childhood and youth. 3.Authors, American — Homes and haunts — Indiana — Mooreland. 4.Authors, American — 21st century — Family relationships. 5.Authors, American — 21st century — Biography. 6. Mothers and daughters — Indiana. 7. Mooreland (Ind.) — Social life and customs.

PS3611.I46 Z474 2006

813’.6 — dc22 2005051964

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-9597-0

ISBN-10: 0-7432-9597-8

The author gratefully acknowledges permission to quote from

The Skin of Our Teeth,

by Thornton Wilder. Copyright © 1942 The Wilder Family LLC. Reprinted with permission from Tappan Wilder and The Wilder Family LLC.

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

www.SimonandSchuster.com

I greatly admire the two-word

DEDICATION PAGE.

I am even moved and puzzled by those books which bear no

Dedication or Acknowledgments page at all,

As if the book were composed on a rocky knoll

By the Muse alone.

MAYBE NEXT TIME.

This book is dedicated, first and foremost, to my incomparable

mother, Delonda Hartmann.

It is also for my brother and sister, Dan Jarvis and Melinda Mullens,

And in memory of my father, Bob Jarvis, and grandmother Mom Mary.

It is for Elaine, Rick, Jenny and Jessica, Josh and Abby,

And Wayne, who got The Girl after all.

It is for Beth Dalton, brave and true friend of thirty-six years,

Whose heart has never closed to me, and who allows me

To stand and consider with her

The Molly-shaped hole in the world.

It is the only way I will ever know how to thank

Julie Newman.

It is for my beloved Amy Scheibe.

It is for Christopher Schelling, who read it on the subway

And in the dead of night and while he had a fever.

Stars are being hammered onto his crown right this second.

It is dedicated to the people of Mooreland, Indiana,

With my abiding gratitude for their support and fine sympathies.

For my mistakes, misjudgments, and glib unkindnesses,

I hope to someday be forgiven.

It is for Ben.

It is for my children, Kat and Obadiah, who are even now writing the

story of their own Time and Place.

And this book is John’s,

As they all have been and all will be.

I Knew Glen Before He Was a Superstar

A Short List of Records My Father Threatened to Break Over My Head If I Played Them One More Time

A few years ago I wrote some essays about the town in which I grew up. Mooreland, Indiana, was paradise for a child — my old friend Rose and I have often said so — small, flat, entirely knowable. When I say it was small I mean the population was three hundred people. I cannot stress this enough. People approach me to say they, too, grew up in small towns and when I ask the size they say, “Oh, six thousand or so.” A town of six thousand people is a wild metropolis. Once a woman told me that she’d grown up in a small town of

fifteen thousand,

and I was forced to turn my head away from her crazy geographic assessment. These people do not know small. Of course there was the elderly woman who told me she was reared in a hamlet with a population of twenty-six. I offered to be her servant for the rest of her life but she was too polite to accept.

Because the town was so knowable and the times they were a-changin’ (it was the sixties and the seventies), Mooreland was blessed with a cast of characters my family and I found interesting and so we talked about them a lot over the years. There were my parents themselves, of course, and my brother and sister, my most-loved grandmother, Mom Mary, and my aunt Donita. There was the woman who lived across the street from us, Edythe, who daily threatened to kill my cats and who, in fact, was not averse to snuffing out my own life, to hear my sister tell it. There were my best friends, Rose and red-haired Julie, and their parents, who, without a sigh or a complaint where I could hear it, kept me relatively clean and well fed. There were my next-door neighbors, the kind and lovely Hickses, and all the people of the Mooreland Friends Church. But for character nothing rivaled the town itself, the three parallel streets bordered at the north end by a cemetery and at the south by a funeral home. It was the dearest postage stamp of native soil a person could wish for.

I started writing the essays as a way to amuse my mom and sister. I’d write something, call, and read it to them. I had no ambitions for the essays and one need only read the above paragraphs to understand why. Indiana is not the state our national eye turns toward for fascinating narratives, strangely enough. Mooreland is definitely not a mecca for the literary arts, although it is rich with crafts. And

no one

cares about the reminiscences of one more child with one more set of parents and neighbors and friends. I myself have been known to wince as if stabbed with wide-bore needles when faced with yet another coming-of-age memoir.

So I wrote my essays with nothing much in mind and eventually there were so many essays about nothing they made a book and then I don’t know what happened. I turned around one day and the book was taken on by a publisher and then it had a cover — and I am talking about the most unfortunate cover imaginable: me as a six-month-old baby, wearing a dress my mother made. I was a tragic little monkey child: bald, with the kind of ears that look fine on woodland creatures but in human culture tend to be corrected surgically. I was holding Mom’s watch, which was dripping with drool, as I was teething. I’m sorry, I need to say this all again.

On the cover of the book was my cross-eyed monkey baby picture, holding a drool-drenched watch.

I nearly fainted the first time I saw it. I called my editor and asked if she was serious and she said yes. Thus did

A Girl Named Zippy

skitter out into the world, and thus was my self-respect laid to rest.

I didn’t expect much from that little book. I was and remain surprised that some people bought it and liked it. But even though it was kindly received in some quarters, I swore I’d never write a sequel. I don’t like sequels, by and large, although sometimes they are welcome. The most important reason to forgo a follow-up was that I’d already sent strangers uninvited into the town and the lives of people I love and respect and I could not imagine doing so again.

A strange thing happened, though, on the many book tours that supported the publication of

Zippy

and of my two novels. In every city I was asked what became of the people I’d drawn — according to my own lights and in keeping with my memory of them — where they were now and if they were happy. That was to be expected. But I was also

always

asked this: “What about your mom? Did she ever get up off the couch?” The first time I heard the question a little bell rang on a faraway hill, and I knew if I ever did (and I wouldn’t) write a follow-up (which I absolutely

would not do

), that would be the subject and that would be the title.

Of course I gave in to the six or seven people clamoring for a sequel. In the beginning I didn’t intend to write anything but a continuing portrait of my family, in particular of my mother. Toward the end of

Zippy

my father and I watched Mom pedal away on my new bicycle, riding toward points unknown; we knew something was afoot but we didn’t know what.

She Got Up Off the Couch

begins at that point — it seemed an appropriate jumping-off place for a book about an individual woman in a very particular place. But when Rose read the final draft she pointed out that Mother’s evolution, personal as it was, is also the story of a generation of women who stood up and rocked the foundations of life in America. They didn’t know they were doing so — they were trying to save their own lives, I think — but in the process they took it on the chin for everyone who followed. I know my own mother did.

I will never do anything half so grand or important. I couldn’t tell this story any way except through my own eyes, but that doesn’t make me the star of the show. As

Zippy

was a bow to Mooreland, Indiana, this is a love letter, humbly conceived and even more modestly written, to my father, my brother, the sister who is my very breath of life, and most of all to the woman who stood up, brushed away the pork rind crumbs, and escaped by the skin of her teeth. It is a letter to all such women, wherever they may be.