Shadows Still Remain (8 page)

Read Shadows Still Remain Online

Authors: Peter de Jonge

When O'Hara returns to the Seven, the air in the room has gone flat and homicide detectives she's never seen before are sprawled at the desks normally used by Krekorian, Navarro, Loomis and herself. The homi guys look like salesmen stranded overnight in a small airportâGrimes's expression the sourest of allâand one look into the box at Lowry's massive sagging shoulders confirms that their prime suspect hasn't budged.

“Grimes,” says O'Hara, turning away from the window and mimicking the way the detective held his fingers a millimeter apart. “McLain still this close to giving it up? Or were you bragging about your dick again?”

The homi guys, who don't seem particularly fond of Grimes either, find this highly amusing. Maybe Lowry hears one of them laugh, because seconds later, he storms out of the box. “O'Hara,” he says, “where do you keep your civilian complaint forms?”

O'Hara points to the top of a filthy file cabinet. “Why?” Without responding, Lowry takes one and goes back inside, and from the small window, O'Hara watches Lowry slide the paper across the table toward McLain. “I'm tired of your cute

bullshit,” says Lowry. “Tell me what happened Wednesday night or fill out one of these.”

“What is it?” asks McLain.

“It's a civilian complaint form. Here, you can use my pen.”

Confused and scared, McLain looks at the form and then up at Lowry, who has taken his .45 from his holster and stepped to McLain's side of the steel table, where McLain's right wrist is handcuffed to one of the legs.

“What happened Wednesday night?” asks Lowry. “I don't know, “says McLain. “I've been trying to tell you thâ¦,” the last part inaudible as Lowry pulls McLain's head back by his hair and shoves the gun barrel down his throat. “For the last time,” says Lowry, “what happened?” McLain shakes his head and gags.

O'Hara waits for Lowry to put his gun away. Then she slaps the door and without waiting for a response, steps inside. “I need to show you something important,” she tells Lowry, but doesn't let herself look at McLain. Furious, Lowry follows her out of the box into the short corridor, two mismatched bodies wedged into a space the approximate size of a phone booth, and stares incredulously as O'Hara hands him a printed receipt from Key Food.

“At one-thirty on the morning Pena was killed,” says O'Hara, “McLain went to a grocery store on Avenue A and purchased twenty items for a Thanksgiving dinner for himself and Pena. At 1:55 a.m., when he walked out of Key Food, he was carrying $119 worth of groceries, including a ten-pound turkey, potatoes, mushrooms, pecans, cauliflower and brussels sprouts. There is no way on this Earth a guy buys brussels

sprouts for someone at 1:55 in the morning, then tortures, rapes and kills that same person three hours later.”

Lowry looks bad and smells a lot worse, four hundred pounds of fat-man body odor, spiked with rage. When he talks, O'Hara feels the heat of his foul breath on her skin. “O'Hara, I don't care if you're a vegan, an idiot or insane. You interrupt one of my interrogations again, I'll have your shield.”

Lowry goes back inside and sits down across from McLain, and O'Hara returns to her post outside the door. But something in Lowry has dissipated, and just before six in the morning, he books McLain on a phony little marijuana charge and sends him to Rikers, figuring the place and its inmates can pick up where he's left off. O'Hara knows it's bullshit, but there's nothing she can do. She tries not to think about a soft teenage kid fending for himself in the city's biggest jail.

Nearly as hungry as she is exhausted, O'Hara drives to a diner on Second Avenue. From her crome-and-vinyl stook she watches the Hispanic cook calmly preside over five sputtering orders of eggs, one of which is her mushroom, pepper and onion omelet. The space behind the counter in which the cook has to maneuver is twenty-four inches wide and some fifteen feet longâ

imagine a cop spending his twenty years walking a beat that size

âbut O'Hara can tell he's happy in his work and gives his customers something more than just good food. She gratefully devours her perfect breakfast, then walks back to her car and sits in the sun behind the wheel. For the next forty minutes she slips in and out of sleep.

At some point during the night, O'Hara's seventy-two-

hour tour with homicide came to an unmarked end. What she should do is go home to Bruno, drink a bottle of red and enjoy the most underrated perquisite of her sex, which is the ability to sleep uninterrupted for sixteen hours. Instead she drives west a couple of blocks and parks on Mercer just north of the Angelika Film Center.

When Pena left her apartment for the last time Wednesday night, she told McLain she was going to meet her friends for dinner. O'Hara already knows that's not true. The downtown debutantes didn't meet up with Pena until 10:30. Pena told her girlfriends that she had spent the previous couple of hours at the NYU gym, running laps on the rooftop track, and O'Hara can see a corner of the track from where she's parked.

O'Hara doesn't think that's likely either. If Pena was working out, she wouldn't have to lie about it to McLain, unless of course, being in her tiny apartment with her lovesick ex-boyfriend was driving Pena so crazy, she couldn't breathe. In that case, she might have said anything to get out, figuring she could decide what she was really going to do once she hit the street. O'Hara knows what that's like.

As O'Hara approaches the entrance, a student holds his ID up to a scanner and pushes through a turnstile, so it should be straightforward to determine whether or not Pena was at the gym. O'Hara shows her badge, and a guard walks her to a small office, where a student employee pulls a chair up to his desk. “People on the track team are here at all hours,” he says. “What time do you want to check for?”

“About eight-forty-five p.m., last Wednesday,” says O'Hara. “November twenty-third.”

“Then I can tell you right now she wasn't here. That was the night before Thanksgiving. We closed the gym at five.”

“Did Pena have an assigned locker?” asks O'Hara.

He glances at his screen. “One seventeen.”

“Has anyone been here to look at it yet?”

“Not that I know.”

The student pages a burly Polish custodian, who finds O'Hara a pair of rubber gloves and a plastic bag. Rather than going with her, which would require closing the girls' locker room, he gives O'Hara the master key. Number 117 is at the end of a row of full-size lockers allocated to varsity athletes. Several pairs of sneakers are piled at the bottom, and shorts, shirts, and running bras hang from the hooks. On an upper shelf beside some toiletries is a stack of expensive-looking envelopes, and when she pulls them down she sees that they've all been sent by one person. O'Hara carefully opens the top one. “I feel like I just got off a train at the wrong station and the joke's on me,” she reads. “I think you made a hasty decision and you'll regret it, but right now all I want to do is fuck you, plain and simple.”

The blunt, aching horniness of that last line takes O'Hara by surprise and reminds her that it's been too long since she's felt anything like it. Then she opens and reads the four remaining notes, which are just as direct and unrequited. All five are signed “Tommy.”

O'Hara carefully slides them into the plastic bag and walks

out to her car. At this point, O'Hara is so exhausted she can barely see straight, yet one question bobs to the surface on its own. If Pena wasn't impressed by a guy who can make turkey stuffing and cranberry sauce from scratch, and wasn't stirred by expressions of honest heartfelt lust, what or who did she want?

Saturday morning, buoyed by a night and a half of dreamless sleep, O'Hara steers her Jetta onto the Henry Hudson Bridge and heads for lower Manhattan. With her homicide tour expired, it's back to the usual Seventh Precinct bullshit, but as O'Hara drives past the George Washington Bridge and the Seventy-ninth Street Boat Basin and the latest crap from Trump, she doesn't feel deflated. And when she exits at Twenty-fourth Street and flips open her cell and dials the number for the precinct, she understands why. She never intended to go back to work in the first place.

“I need a day off, Sarge,” she tells Callahan. “I'm burnt to a crisp.”

“Then take one, Darlene. You deserve it. More than deserve it.” If Callahan weren't such a useless prick, she might almost feel bad.

O'Hara continues east to First Avenue, her rattling Jetta showing its 97,000 miles, finds a space on Thirty-first Street and walks into the office of the medical examiner. Lebowitz's door is closed, and when she knocks, she hears a drawer slide shut before he tells her to come in.

“Working on your screenplay?” asks O'Hara.

“No screenplay,” says Lebowitz as he opens his drawer and holds up the recondite medical journal he had been busted in the process of reading. If O'Hara is not mistaken, the thirty-two-year-old ME is blushing. “And I'm not consulting on

Law & Order

or

The Wire

. I'm the only one here who isn't.”

“You don't like money?”

“Never had any, I wouldn't know. But I like my job as it is. I'm not trying to parlay it into something else. You here about Pena?”

“Yeah,” says O'Hara. “I was hoping to take another look. I'm trying to make sense of all those wounds, the gouging in particular.”

“It's an unusual way to torture someone,” says Lebowitz. “And hard work.”

As Lebowitz walks O'Hara down the hall, she gets her second surprise of the morning. Not only does Lebowitz blush and avoid eye contact, he moves well, like an athlete. In the morgue, he slides Pena's body out of her refrigerated locker onto a gurney and unzips the heavy plastic pouch. Seeing the ghostly Pena on her back, O'Hara is struck by the distinct halves of a long-distance runner, the torso spare and delicate, the thighs sturdy and powerful. “A pretty amazing body,” says O'Hara.

“If you like skinny dead girls,” says Lebowitz.

“The problem,” continues Lebowitz, “is there are so many gouges, it's impossible to focus on any of them. Let's break her into quads and see if that helps.” He pulls the top zipper down to the middle of Pena's neck and the bottom zipper up to her waist, so that only the area between her shoulders and hips is exposed. “This should make it less overwhelming.”

On the front of Pena's torso, Lebowitz counts twelve gouges. “The wounds show almost no consistency,” he says. “In length they range from six inches to an inch and three quarters; in depth, from over an inch to little more than a scrape.”

Lebowitz then covers Pena's upper half and exposes her legs. This quadrant has fewer gouges (nine), and they're smaller and shallower. “The blade was getting duller,” says Lebowitz, pointing at the rough edges. “The killer must have worked his way from the top down.”

“And it looks like he was getting tired,” says O'Hara. “The work is getting sloppier.”

“Or maybe he's losing enthusiasm. By now the victim would probably have lost consciousness.”

When Lebowitz rolls Pena over, they can see at a glance that the wounds on her back are larger and deeper than those on the other three quadrants, and the edges of the wounds are the cleanest, indicating that this is where the gouging began. “If someone was torturing someone,” says Lebowitz, “you'd think they'd start on the front, where the victim would be able to see what was happening to her.”

“Is there any way of determining which gouge was made first?” asks O'Hara.

“Not with certainty. But if I had to pick, it would be this one.” Lebowitz points to a rectangular wound about the size of a credit card on the right side of Pena's lower back. “It's deep, and the edges look especially clean. The attacker clearly took his time with this one.”

Lebowitz pulls latex gloves over his long fingers and with

a scalpel cuts a very thin slice from the center of the wound, places the cross section on a glass slide and walks it to a scuffed-up microscope on a nearby table. In high school, Lebowitz would have been the kind of nerd O'Hara would have shunned and, maybe even worse, given a hard time. But as he carefully takes off his wire-rimmed glasses, pushes back his dark unruly hair and bends over the eyepiece, O'Hara realizes she's become more open-minded. What she would like to do to Lebowitz now is stick her tongue in his ear.

“Sam?”

“What?”

“Thanks for calling me directly about the DNA and not just telling Lowry. I really appreciate that.”

“I couldn't help myself,” says Lebowitz. “I'm a Knicks fan. I root for the underdog.”

“One other thing.”

“What's that?”

“Before, when you said you didn't like dead skinny girls, were you just saying that? Or did you really mean it?”

“Every word of it,” says Lebowitz, grinning but not turning from the eyepiece. “I'm a sucker for a pulse.”

“One last thing, Sam?”

“What's that, Darlene?”

“You see anything in there?”

“Yeah.”

“What?”

“Ink.”

If you don't think women are suckers, check out the visitors waiting room at Rikers on a Saturday afternoon. The dingy space holds two hundred plastic chairs, and there's a dolled-up woman in every one. The only male visitors are babies and toddlers. These girls can barely keep their own head above water, and they've all spent way more money and energy than they can afford to put on a good show for some punk. Even their kids are decked out in miniature shearlings and Baby Gap.

In her standard-issue overcoat, slacks and sensible shoes, O'Hara is conspicuously underdressed, but most of the looks she gets are smiles, the girls assuming she's in the same leaky boat as them until a guard escorts her out of the room. “What about me?” shouts a girl who can't be more than nineteen. “I've been here two hours already. She ain't been here twenty minutes.”

“She's a cop,” explains someone smarter.

The guard leads O'Hara down a hallway smelling of watered-down cleanser and into a narrow room split in half by a Plexiglas wall. Inmates are on one side, their girls and babies on the other, and though the room is packed, it's remarkably

quiet, everyone, even kids, doing their best to help their parents carve out a little privacy.

McLain's got a spot near the center of the room. When O'Hara sits opposite him, she sees the deep bruise above his right eye, the swollen lip and the cuts on the side of his head. The only good news is he's fighting back. The knuckles on both hands are swollen and raw.

“I hope you're holding your own,” says O'Hara.

“Don't have much choice.”

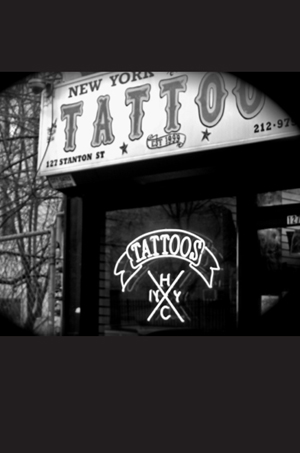

“Sorry about that,” says O'Hara, “and sorry I couldn't do more at the precinct. But I got to ask you somethingâdid Francesca have any tattoos?”

“Yeah.”

“Where were they?”

“She only had oneâ¦on her lower back, off to the right. When she came home at the end of September, she had just gotten it.”

“You know what it was?”

“All I remember is a big heart with an

S

inside, but I barely saw it. Francesca said it had to do with her father and didn't want to talk about it, which I thought was strange. I mean, don't get a tattoo if you don't want to draw attention to something. But with her father a junkie and dying of AIDS, that whole time in Chicago was pretty much off limits. So I let it go.”

“Francesca ever mention a guy named Tommy?”

“Who's that?” asks McLain, struggling to keep the hurt from showing in his banged-up eyes and mouth.

“I don't know. I found a note in her locker.”

When McLain shakes his head no, O'Hara takes a card out of her wallet and holds it to the glass. “I know the police got you a public defender, but here's one that actually doesn't suck. Her name is Jane Anne Murray. She's expecting to hear from you. But don't use my name on the phone. A detective will probably be listening to your calls.”