Shadow Divers (28 page)

Metal schematic diagram discovered by Chatterton. It was this artifact that confirmed the U-boat’s type and the shipyard at which it was built.

RICHIE KOHLER

A few of Richie Kohler’s

U-Who

artifacts, including a metal schematic diagram, the face of the diesel motor room telegraph, directions for use of a survival kit, and a glass bottle for cologne, which submariners used to mask the odors of months at sea.

JOHN CHATTERTON

One of the U-boat’s steel hatches, likely blown open by the force of an immense explosion.

NOVA /WGBH-TV BOSTON

Tight squeeze: Richie Kohler entering the diesel motor room through a control room hatch.

SUSAN ROUSE

Chris Rouse, left, and son Chris Rouse, Jr., aboard the

Seeker

after diving the

Andrea Doria

in 1992.

JOHN CHATTERTON

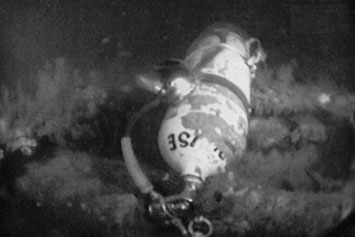

Chrissy Rouse’s penetration line, tangled after his desperate attempt to escape the U-boat.

JOHN CHATTERTON

One of the Rouses’ scuba tanks, still lying on the wreck after their fateful dive.

RICHIE KOHLER

Reunited. Richie Kohler and John Chatterton in the summer of 1996, after Kohler’s self-imposed exile from diving.

“You and Danny take the boat,” Nagle said, ice clinking in the background. “I don’t give a shit. Go without me.”

On the night of October 10, the divers gathered at the

Seeker’

s Brielle dock. No one had to ask why Nagle was not in the wheelhouse.

While the other divers tied down their gear, the Rouses began their bickering. This time their argument was a bit more serious than usual. Neither father nor son could afford trimix for the trip—they would be forced to breathe air, a savings of a few hundred dollars.

“Chrissy was supposed to buy the mix this time,” Chris sniped.

“No, it was the old man’s turn,” Chrissy countered.

“Was not.”

“Was too.”

“Cheapskate.”

“Miser.”

And so on into the evening.

The next morning, Chatterton and Kohler splashed first, as had become their custom. While Kohler explored the NCOs’ quarters, Chatterton returned to the forward torpedo room in search of more tags. He found a few made of plastic, but none with identifying information. On the way out, he spotted a bent piece of aluminum about the size of a tabloid newspaper lying amid a pile of wreckage. Ordinarily, he would have ignored such junk. This day, something urged him to pluck it from amid the garbage and drop it into his bag. Chatterton gave the artifact no more thought as he began his ascent to the

Seeker.

Topside, Chatterton emptied his bag. The aluminum piece, Swiss-cheesed by rust and splotched with marine growth, clanged onto the dressing table. Yurga walked over to inspect it. Chatterton opened the bent metal as if it were a magazine. Engraved on the inside were technical diagrams—a schematic illustrating the mechanical operations of some part of the U-boat. Chatterton grabbed a rag from a bucket of fresh water and wiped it across the artifact. The sea growth lifted easily, revealing small German inscriptions along the tattered bottom edge. Chatterton pulled the schematic toward his face. He read, “Bauart IXC” and “Deschimag, Bremen.”

“Hold everything,” Yurga said. “Deschimag-Bremen was one of the German U-boat construction yards. That means this wreck was a Type IXC built at Deschimag-Bremen. There couldn’t have been more than a few dozen Type IXs built there during the entire war. This is huge for our research.”

Kohler surfaced a few minutes later. Like Yurga, he understood the magnitude of the discovery.

“This is really going to narrow things down,” Kohler said, slapping Chatterton’s back. “All we have to do is go home, check our books, and we’ll have the short list of IXCs built at Deschimag. It’s gorgeous.”

The divers splashed again that day but found little. Their minds, in any case, were on Chatterton’s spectacular find. That evening over dinner, as the

Seeker

rocked in the waves while anchored to the U-boat, the Rouses admired the schematic and told Chatterton about their day. They had nearly excavated the piece of canvas covered in German printing and believed they might be a dive away from bringing it topside. Optimism echoed off the salon walls. The divers wished one another a good night. In a single day, a season of dead ends had transformed itself.

The Atlantic recused itself from the divers’ optimism. As men slept aboard the

Seeker,

the ocean turned the vessel into a bathtub toy, tossing some divers from their bunks and forcing the captains, Crowell and Chatterton, to consult the weather radio. Conditions were snotty with five-foot waves, and the forecast had changed for the worse. At 6:30

A.M.

Chatterton walked down to the salon and roused the divers.

“It’s getting nasty out there,” Chatterton said. “Anyone thinking of diving best get going now. After that, we’re pulling the hook and going home.”

“You diving, John?” someone asked.

“Not on a day like this,” Chatterton said.

Of the fourteen divers on the trip, just six moved from their bunks to gear up. Kohler was first and dressed without hesitation. A half hour later he rolled into the ocean. The dive team of Tom Packer and Steve Gatto followed, as did New Jersey State Trooper Steve McDougal. The Rouses also rolled out of bed.

“I’m not diving, forget it,” Chrissy said, peering out a cabin window. “Too rough out there.”

“You pussy!” his father bellowed. “You got no backbone, kid.”

“Didn’t you hear, old man?” Chrissy asked. “Chatterton said the weather’s nasty and getting worse. Can’t you feel it out there?”

“If you can’t dive these conditions, you got no business being out here,” Chris said. “I can’t believe you’re my son. You’re an embarrassment!”

“Okay, you old crow,” Chrissy said. “You want to go diving? We’ll go diving. Let’s go.”

For a moment Chris said nothing.

“Ah . . . that’s okay,” Chris finally said. “I was just jerking your chain. It really is too rough. Let’s pass.”

“Too rough? Maybe too rough for you, you old geezer,” Chrissy said, taking the offensive. “If you’re too soft to go diving, I’ll go myself. You stay here with the women.”

“You’re not going without me,” Chris said. “If you go, we both go.”

“You guys are too much.” Chatterton laughed, leaving the salon. The Rouses continued bickering as they decided what to have for breakfast, whether to shave, how long their dive should last. Chris jokingly ordered Barb Lander, the only woman aboard, to fix his breakfast and wash his dishes.

As the Rouses geared up they reviewed their plan. Chrissy would return to the galley to free the piece of canvas containing the German writing. It was stuck beneath a floor-to-ceiling steel cabinet. Chris would wait outside the wreck, his lights a beacon for his son’s exit. Chrissy would work for twenty minutes before exiting the wreck. At the dressing table, the Rouses affixed their trademark hockey-style helmets and started for the gunwales. Waves battered the

Seeker’

s stern, knocking the flipper-footed Chrissy onto his side like an overtired toddler. Yurga forklifted him under the arms and stood him upright. Another wave rocked the boat. This time Chrissy did a face-plant onto the deck.