Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (7 page)

Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

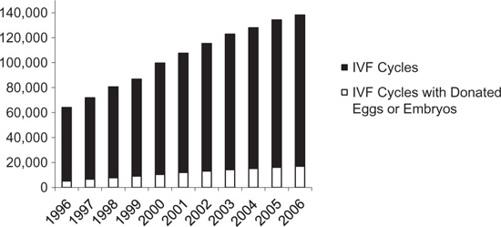

Figure 1

. Proportion of IVF cycles involving donated eggs or embryos, by year

Up until the early 1990s, most physicians had very little experience providing IVF with egg donation; one survey revealed that just 10% of fertility clinics had performed more than ten cycles in the previous two years.

38

However, by the time the CDC started tabulating statistics on IVF in 1996, there were more than 300 fertility clinics in the United States, 74% of which offered egg donation. Over the next decade, the number of IVF cycles performed in the United States rose steadily, from around 64,000 per year to nearly 140,000 in 2006, with the proportion of those involving donated eggs or embryos growing from 8% to 12% (see

Figure 1

).

39

As IVF with donated eggs became more popular, especially among older women, physicians had trouble keeping up with the demand. The first commercial egg agencies opened their doors around 1990, offering

rosters of women willing to provide sex cells in return for financial compensation. One of the earliest programs, and now one of the largest in the country, OvaCorp, emerged out of an established surrogacy agency on the West Coast. A psychologist there, who had already been screening surrogate mothers and matching them with recipients for several years, described receiving two phone calls around the same time in the late 1980s. One woman had been diagnosed with premature ovarian failure, and she called saying, “I don’t need a uterus. My uterus works fine. Do you think any of the women who are volunteering to be surrogates would volunteer just to give me their eggs?” The psychologist replied that she did not know and promised to get back to her. After talking with the agency’s owners, she decided to ask a few women who had previously served as surrogates. She explained, “They’d already given up a whole baby, so giving up an egg seemed relatively easy.” The second call came from a woman who said, “I’d really like to help someone, but I hate being pregnant. Is there anything I could do? I waste eggs every month.” As in the physician’s description of one of the first egg donations in a medical setting, the gendered tropes of giving and helping also appear in this narrative of one of the first egg donations in a commercial setting.

In explaining the significance of these two calls, the psychologist pointed out that “egg donation was certainly going on. It wasn’t like we had never heard of it, but the idea that we would be involved had not ever dawned on us.” But compared to surrogacy, which had been so controversial, egg donation “was a piece of cake,” and “pretty soon [the agency’s owners] understood that this was going to be something. They started advertising for donors and letting doctors know that we were doing it.”

Women who donated eggs in the early 1990s were paid between $500 and $3,500 per cycle.

40

In deciding how much to pay egg donors, one physician–researcher said he set the fee based on a “gut reaction to what would be reasonable.” Others were more systematic. The Cleveland Clinic assigned economic value to each stage of the donation cycle, paying women $50 for each day they received injected hormones or had blood drawn; $100 for days when they received injected hormones, had blood drawn,

and

had an ultrasound; and $350 for the day of egg retrieval.

This usually resulted in a total payment of $900 to $1,200 per cycle.

41

Similarly, the psychologist at OvaCorp said she “sat down and really calculated how many appointments” donors attended, because she believed that “women’s time was worth something.”

We decided $2,500, based on the fact that surrogates got 10 or 12 [thousand dollars] for fifteen months of work [in the late 1980s]. A donor was going to have to commit for three months by the time they did five intakes, injections, their pain and suffering physically. Nothing compares to labor I guess, but it was uncomfortable. Also, we wanted it to be an amount of money that was respectful, but not enticing. They get the money whether there is a pregnancy or not, so you wanted women to do it because they were going to do a good job, not just because they were dirt poor. It felt right. No one argued with that fee. The doctors weren’t uncomfortable. The couples weren’t uncomfortable.

The founder of what is today another major egg agency on the West Coast noted that when she opened in 1991, $2,500 was the “going rate,” so that is what she paid donors.

In figuring out how to recruit egg donors and match them with recipients, OvaCorp also did not look to sperm donation as a model. The psychologist explained, “We came from the adoption world and the surrogacy world, not the sperm donor medical world and organ donor world. So we just did it from a very informed consent, patient advocacy, you’ve-all-agreed-prior-to-conception, all-cards-on-the-table perspective versus let’s micromanage information and the doctor-will-have-the-only-copy model.” Committed to the open flow of information between donor and recipient, she did not

allow

anonymity, requiring that both parties meet one another. She explained the process.

I would meet with the parents to narrow down what they were looking for. I would present them with a couple of choices, not a catalog. The couples were not obsessively picky, because that wasn’t the market at the time. There weren’t twenty [egg] agencies to go to. Then I would set up a meeting with the recipients and the donor at my office. We’d sit and talk for an hour and a half. If they liked each other, then the attorney would draft a contract. We would send them to the IVF clinic, and they’d be on their way.

Although the process of characterizing the material happened very differently in the first commercial egg agencies than it had in the sperm banks, information about the donors was deemed similarly powerful in attracting customers. According to the psychologist, OvaCorp was soon hearing from recipients all over the world.

. . . If [the recipients] wanted to know more, have control, wanted a specific type of genetic history, Chinese, Jewish, harder-to-find donors. If they lived in a small town and knew the [egg] donors were the two nurses downstairs, that was too weird. If a couple was from overseas and the waiting list was really long, they’d come to us, and we’d match them with a choice of donors within a few months. That’s no big deal now, but it was a big deal in 1990 because there was the idea of choice, the idea of information.

In fact, one of OvaCorp’s first clients was a couple from New York whose university donation program did not have any African American donors. OvaCorp’s psychologist recalled, “They called me, and I said ‘Sure; her name is Michelle. When would you like to meet her?’ I only had a few, but I had them. So they came all the way to California, paid handsomely for it, instead of doing it right in New York.”

Indeed, the situation was very different on the two coasts. Commercial egg agencies did not open in the East for several years, and a West Coast physician–researcher describes a similar situation in the 1990s, when he had “patients coming from New York, because they were much slower in developing egg donation and good numbers of egg donors.” To this day, physician-run programs in the East are more insistent on anonymity and reveal less information about egg donors. The founder of the second egg agency to open on the West Coast explained that “the main difference was not showing pictures [of donors]. People didn’t believe, and still don’t believe, that an egg donation needs to involve a photograph. The doctors can control that. We get those calls all the time.”

Given their proximity to the nascent commercial egg agencies, doctors on the West Coast began to adopt similarly open policies. One physician–researcher described how, as was standard practice in sperm donation, “initially, we were matching [egg donors and recipients]. Then

gradually we got wind of the fact that other places were showing people pictures, and we had a big debate about whether we would show pictures. We decided that that would really demystify it, so we started showing pictures.” These kinds of innovations eventually made their way back to sperm banks, evident in Gametes Inc.’s and CryoCorp’s decisions to start providing additional information about sperm donors in the 1990s. However, while some sperm banks offer baby photos of donors, many, including CryoCorp, still do not provide adult photos and most do not allow meetings between sperm donors and recipients.

OvaCorp’s first major competitor, founded by a therapist who herself had undergone treatment for infertility, opened in 1991. When asked how she went from patient to broker, she also referenced the importance of information.

There were sperm donor programs and surrogacy programs, but there wasn’t an organized way of finding egg donors. Other than OvaCorp, there really wasn’t anybody saying we have a roster of women, here’s information about them. I went up to my doctor and said “I think I can help you. I think I can recruit egg donors.” I knew there was a need, and doctors are really busy, so if you take a burden off their shoulders, they’re thrilled [

laughs

]. He said absolutely, because he knew me. I went around knocking on other doctors’ offices, but only one really got behind the idea. He was wonderfully supportive, started referring me patients, and we did a number of donations together. The other doctors were real closed about it. Two years later, I began to have success and became known in the industry, and of course they were calling me: “Why aren’t you working with us?”

Indeed, some egg agencies receive enough inquiries from patients to serve as an important referral source for physicians, with one founder noting that it can “make you really powerful.”

Although OvaCorp required that egg donors have children of their own, the new program did not, and the founder also focused her recruitment efforts on the local entertainment industry. She explained that, in the early 1990s, it was not obvious where to find donors.

Back then, no one knew what [egg donation] was. I had been an actress. I thought, actresses have time off, they’re attractive, and they’re usually fairly bright. I ran an ad in [an acting newspaper] saying, “extremely rewarding emotionally and financially, become an egg donor.” I had about 75 calls for the first ad, and it went from there.

It was around this time that OvaCorp’s psychologist was “having lunch with a very well-known IVF doctor. He said, ‘you better take note, that new agency is going to be really great. Their donors are models and actresses and really high quality. You got competition.’ ” Indeed, as the number of commercial egg agencies began to grow, many allowed women without children to become donors, and OvaCorp was forced to change its policies “to compete.” Once it did so, the psychologist explained, “of course, OvaCorp had hundreds more donors.”

In the early 1990s, there were just a few commercial agencies, but by the end of the decade, one program director described them as “escalating exponentially. It’s insane how much competition there is.”

42

One of the new agencies, Creative Beginnings, was founded in 1999 by a nurse who had worked in fertility practices for years, including a period in which she managed a prominent physician–researcher’s egg donation program. Like several other women with this background, she decided to strike out on her own, explaining “I have a reputation for starting [this physician’s] donor program, co-authoring research with him. Doctors tell me they’re really happy to see me doing this, that I come from the right background.” When she was working for physicians, she explained,

I would get donors from all these different [agencies] that were not informed, didn’t know what they were getting into, and I had donors I couldn’t get a hold of. The nurses have to educate them, make sure they do this right, and if they don’t, it’s the nurses’ fault. I didn’t have very much power. And then I saw they were totally inappropriate when I’d read their medical history.

It was for these reasons that the founder of Creative Beginnings thought of herself as the “right person” to open a commercial egg agency.

Whereas compensation to sperm donors had rarely generated much debate, questions about whether and how much to pay women for providing eggs were raised early and often, including in editorial exchanges in the

New England Journal of Medicine

in 1993 and

Fertility and Sterility

in

1999.

43

This latter exchange was sparked by a New York donation program’s decision to raise donor fees in 1998, in the words of the editorial writer, “to double the compensation from the community standard of $2,500 to a startling $5,000 per cycle.” Indeed, the price hike was covered on the front page of the

New York Times

.

44

The physician responsible for the increase justified it on the grounds that he had a six-month waiting list for recipients, noting that most clinics were experiencing “very strong demand” for egg donors. Yet this $5,000 figure, which seemed shocking at the time, was deemed acceptable just a year later in an ASRM ethics statement, which concluded that sums above $5,000 “require justification and sums above $10,000 are not appropriate.”

45