Seven Elements That Have Changed the World (41 page)

Read Seven Elements That Have Changed the World Online

Authors: John Browne

85.

An Intel 22nm transistor. More than six million of these would fit into this full stop.

86.

No Apple and Windows without Moore and Grove: the fathers of the modern silicon chip.

87.

The big man behind silicon photonics: Mario Paniccia.

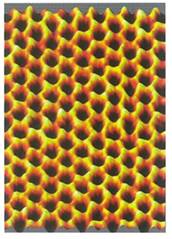

88.

A Microscopic view of a futuristic material: graphene.

Preface

1.

E

VERY ATOM CONSISTS OF

a nucleus, made of protons and neutrons, which is orbited by electrons. Atoms of the same element have the same number of protons in the nucleus. As you move from left to right along the ‘periods’ of the periodic table, the number of protons in the nucleus increases by one with each step. So, too, does the number of electrons, which is the same as the number of protons, and which orbit the nucleus in larger and larger ‘shells’ as their number increases. Elements in the same columns, or ‘groups’, of the periodic table have similar chemical properties because of similarities in the arrangement of electrons, neutrons and protons.

2.

Fossil fuels are produced from dead plants and animals when subjected to intense heat and pressure over a long period of time.

1.

W. H. Bragg,

Concerning the Nature of Things

(London: G. Bell and Sons Ltd, 1925).

2.

By directing x-rays at regular crystal structures, the Braggs were able to determine their atomic structure from the angles and intensities at which these x-rays were reflected. The Braggs won the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.

3.

Bragg,

Concerning the Nature of Things

, p. 6. John Dalton, the English chemist and physicist, hypothesised the existence of atoms of different elements distinguished by their weight. In his theory, presented to the Royal Institution in 1803, these atoms could not be divided, created or destroyed but could be combined or rearranged in simple ratios to form compounds. Later in the nineteenth century, Dmitri Mendeleev, a Russian chemist, noticed a pattern in the chemical properties of the known elements. The weights of elements with similar properties increased regularly. This periodicity led Mendeleev, in 1869, to arrange the elements in rows or columns according to atomic weight; he would start a new row or column when

the chemical behaviour began to repeat. By leaving gaps in the table when no known element would fit, Mendeleev was able to use his periodic table to predict the properties of undiscovered elements.

4.

Ibid., pp. 186-7.

5.

John Browne,

Beyond Business

(London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010), Chapter 10.

6.

Ibid., Chapter 9.

7.

Ibid., Chapter 6.

8.

The ‘Great Leap Forward’ was coined by Jared Diamond in

Guns

,

Germs and Steel

(London: Jonathan Cape, 1997), p. 39.

9.

In

The Meaning of It All

, Feynman writes that science has value because it provides the power to do something. He asks: ‘Shall we throw away the key and never have a way to enter the gates of heaven? Or shall we struggle with the problem of which is the best way to use the key? That is, of course, a very serious question, but I think that we cannot deny the value of the key to the gates of heaven.’ (London: Penguin Books, 1998), pp. 6-7.

1.

Report of flag officer Franklin Buchanan, C. S. Navy. Naval Hospital, Norfolk, VA, 27 March 1862, in Mills, Charles,

Echoes of the Civil War

:

Key Documents of the Great Conflict

(BookSurge Publishing, 2002), p. 118.

2.

Thomas Oliver Selfridge Jr., in David Mindell,

Iron Coffin

:

War

,

Technology and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor

(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), p. 71.

3.

Navy Secretary Welles in Mindell,

Iron Coffin

:

War

,

Technology and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor

, p. 72.

4.

Currier & Ives was a nineteenth-century New York-based print-making firm. It was one of the most successful and prolific lithographers in the US. The lithograph is inscribed, somewhat inaccurately: ‘The Battle of Hampton roads … In which the little Monitor whipped the

[Virginia]

and the whole school of rebel steamers.’

5.

In the lithograph, the USS

Virginia

is referred to as the ‘Merrimac’, after the sunken ship from which the

Virginia

obtained its frame.

6.

William Harwar Parker,

Recollections of a Naval Officer

,

1841–1865

(Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985), p. 288.

7.

G. J. Van Brunt to Welles, Mar. 10 1862, in Mindell,

Iron Coffin

:

War

,

Technology and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor

, p. 74.

8.

Only the

Monitors

captain was injured during the battle when he was blinded by a shell exploding into his eyes through a slit in the armour.

9.

Mindell,

Iron Coffin

:

War

,

Technology and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor

, p. 1.

10.

Mary Elvira, Weeks,

Discovery of the Elements

(Kessinger Publishing, 2003; first published as a series of separate articles in the

Journal of Chemical Education

, 1933), P.4.

11.

Otto von Bismark,

Blut und Eisen

, 1862.

12.

This was the Schwerer Gustav cannon, named after Gustav Krupp, weighing 1,350 tonnes and with a 32-metre-long barrel. In the siege of Sevastopol in June 1942, ‘Gustav’ wreaked destruction on the Soviet naval base. One shot penetrated through 30 metres of earth, detonating inside an underground ammunition store.

13.

The return of Alsace-Lorraine doubled the theoretical steel capacity of France, but it struggled to reach this potential. Shortly after the end of the First World War, France suffered a coal shortage as a result of the destruction of mines and wearing out of rails during the war.

14.

Hitler said: ‘The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If the French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance.’ R. Manvell and H. Fraenkel,

Adolf Hitler

,

The Man and the Myth

(New York: Pinacle, 1973), p. 141.

15.

On the arrival of British and America troops in April 1945 they found that the city had been completely destroyed. To prevent the rise of the Ruhr armament factories, the Allied forces broke up what machinery was left and sent it to neighbouring countries as war reparations. ‘No Krupp chimney will ever smoke again,’ wrote the accountant put in charge of the Krupp factories. As for the Krupps, Alfred Krupp was imprisoned for war crimes and stripped of his wealth, just as his father, Gustav Krupp, had been after the First World War, but was soon released and his property returned to him. Peter Batty,

The House of Krupp

(London: Secker & Warburg, 1966), p. 12.

16.

Robert Schuman,

The Schuman Declaration

, 9 May 1950.

17.

Ibid.

18.

In 1957 the Treaty of Rome created the European Economic Community (EEC), or ‘Common Market’. The Maastricht Treaty, signed in 1992, set the EU on the path towards the euro, launched in 1999 and used today by seventeen of the EU’s twenty-seven members.

19.

In his memoirs, Jean Monnet, a chief architect of the ECSC, writes: ‘Coal and steel were at once the key to economic power and the raw materials for forging the weapons of war. This double role gave them immense symbolic significance, now largely forgotten … To pool them across frontiers would reduce their malign prestige and turn them instead into a guarantee of peace.’ Jean Monnet,

Memoirs

(London: Collins, 1978), p. 293.

20.

In October 2012 I visited the Zeche Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in

Essen for a meeting of the Accenture Global Energy Board, which I chair. Zeche Zollverein is now a museum and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and its iconic shaft 12, built in distinctive Bauhaus style, is known as ‘the most beautiful coal mine in the world’. Zeche Zollverein is typical of the transformation of Western economies from primary and secondary to tertiary industries: having been taken on a guided tour of the coal mine museum, I then spent the afternoon in a conference room on the top floor of the museum.

21.

Unity is, however, far from apparent among member states of the European Union today. The global financial crisis of the later 2000s has led to a crisis of confidence among European member states, threatening the global recovery. Political and economic unions are always susceptible to break-up as, in times of stress, national interests strengthen.

22.

Half of all iron consumed is used for construction purposes, a quarter is used to make machinery and a tenth to make automobiles. Only 3.3 per cent of iron is used in the oil and gas industry.

23.

A detailed account of this period of BP’s history can be found in J. H. Bamberg,

The History of the British Petroleum Company

, Vol. 2:

1928-1954

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 206-29.

24.

The previous largest semi-submersible platform, used to tap the Åsgard oilfield in Norway, had a displacement of 85,000 tonnes (compared to 130,000 tonnes for

Thunder Horse

).

25.

‘Building The Big One’,

Frontiers

, April 2005,

www.bp.com

26.

In

Concerning the Nature of Things

, Bragg writes that, in steel, carbon atoms ‘are forced into the empty spaces between [iron atoms]. We can easily see that this may distort the iron crystal, and prevent the movement along a plane of slip’, p. 226.

27.

Bessemer’s resolve to produce a superior metal was furthered by his invention of rotary action bullets, the circular motion of which improved their range and accuracy. He had made a small cast-iron mortar to prove his concept by firing shells within the grounds of his Baxter House home, but the cast-iron cannons were too weak to withstand the pressure resulting from the heavier projectiles and often broke.

28.

Memoir written in 1890. Joseph Needham,

Science and Civilisation in China

, Vol. 5, Part 11 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), pp. 361-2.

29.

Henry Bessemer,

Sir Henry Bessemer

,

F.R.S.

:

An Autobiography

(London: Office of Engineering, 1905), pp. 143–4.

30.

Precursors to Bessemer’s process exist, such as the ‘air boiling’ process used by William Kelly in the US to make iron railings years before Bessemer’s invention. However, Kelly did not create a liquid product using only air; his was an extension of an existing process, rather than an entirely new process. As far back as the eleventh-century Song Dynasty in China there are records of partial decarbonisation using a cold-air-blast technique.