Seven Elements That Have Changed the World (17 page)

Read Seven Elements That Have Changed the World Online

Authors: John Browne

When Marshall had struck gold in January 1848, California was a small

territory not yet having acquired statehood, with a population, of around 20,000, excluding indigenous people. Within a few years it had a population of hundreds of thousands and by 1880 that was nearly a million. Today it is the most populous state in the US, and one of the world’s largest economies. In California, the scale and success with which gold was invested was unprecedented. Its discovery led to a period of extraordinarily fast development at the time of the US industrial revolution. California was connected with the booming East Coast, both through immigration and the development of railways. It was transformed from an agricultural to an industrial state. Gold underpinned that development through investment. And while the opportunities for gold prospectors had dried up, California’s industrial revolution was providing new ways to make a fortune in the state’s nascent industries. It seemed possible for anyone to get rich quick during this period of unparalleled growth.

In ancient Egypt, gold jewellery was high art, worn by pharaohs to symbolise their power and to assert their proximity to the gods. It was used as gilt for divine statues, temples, obelisks and pyramids. Gold’s connection with the gods meant it was also extensively used to honour the dead, most famously in the mask and coffins of Tutankhamun. By these divine associations, gold became valued and, as a consequence, widely acknowledged as a store of wealth. To do just that, the Egyptians cast gold ingots as early as 4000

BC.

Unlike crops and livestock, gold is neither bulky nor perishable and so it can be used as a means of payment over longer distances and periods of time. It does, however, have some limitations. The value of gold will depend on its purity and there needs to be a way of ensuring this if gold is to be a trustworthy means of payment.

22

In the seventh century

BC,

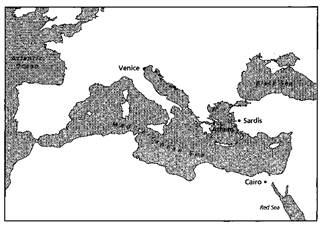

the thriving merchant city of Sardis (the capital of Lydia, the site of which is in modern Turkey) which had an abundant local supply of gold and silver, came up with one of the first solutions to this problem. As the River Pactolus, which passed through the city, meandered on its way towards the Mediterranean coast, it slowed and deposited gold and silver, combined in a naturally occurring alloy known as electrum.

According to Greek mythology, the river bed was given these riches when King Midas bathed in the waters to remove his cursed golden touch. The proportion of gold and silver in electrum varied considerably and therefore its value also varied. In its raw state, it was not a trustworthy medium for payment. However, the Lydians made the electrum into coins, which signified that each coin would be redeemable for its face value, regardless of the actual value of the gold and silver from which it was cast.

23

The difficult and often inaccurate task of testing the electrum’s purity each time it changed hands was no longer necessary. Merchants could place trust in a transaction, without having to trust the individual with whom they were dealing.

In the middle of the sixth century

BC,

during the rule of King Croesus, the Lydians discovered a method for separating electrum into almost pure gold and pure silver by heating it with salt. Croesus became the first ruler to issue coins of pure gold and silver, stamping them with the symbols of the Lydian Royal House, the opposing figures of a lion and a bull, representing the opposing forces of life and death.

24

These overcame the big drawback of electrum coins which were only accepted locally; the pure gold and silver coins, struck with the royal stamp, became accepted internationally and that was important for Sardis. Situated between the Aegean Sea and the River Euphrates, it was perfectly placed to take advantage of the growing international east to west trade routes. Croesus’s coins improved the efficiency and reliability of the growing number of international transactions and his coins soon spread around Asia Minor. Gold was no longer purely a store of wealth for the rulers, but it had been placed into the hands of merchants. As international trade grew, so did the amount of gold and silver changing hands.

As for Lydia, its wealth was frittered away on luxury goods and on Croesus’s ever more ambitious wars. In 546

BC

Croesus attacked Cyrus the Great’s Persian Empire, but this was a step too far.

25

Within a year he was defeated, but his legacy lived on as his coinage was used by the Persians as they pushed westward. Croesus’s invention had turned gold and silver coins into standards, the use of which would, in time, spread across the entire world.

In my library I have a book of very large engravings made by Giovanni Battista Brustolon based on paintings by Canaletto. One of these images shows crowds thronging on all sides of St Mark’s Square, beaten back by men with sticks and dogs. At the centre sits the Doge of Venice, on his

pozzetto

, a type of sedan chair. He has just been inaugurated inside St Mark’s Basilica and that forms the backdrop for the scene. And as he is carried through the square, the Doge throws hundreds of gold and silver coins into the crowd, resulting in a scene of chaos. Here, just as in the depths of the South American jungle, men and women scrambled for gold.

That scene, drawn in the eighteenth century, was of a city that, six hundred years earlier, had become the new trading hub of Eurasia. In Venice, as in Sardis, it was gold currency that underpinned the prosperity of the city. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, east/west trade increased as the economy of Western Europe grew. Silk, spices and other luxurious items were brought into the trading centres of Genoa, Florence and Venice where, because of their rarity, they fetched high prices. So much

gold flooded into Florence that by 1252 there was enough to start minting a new gold coin, the florin. In 1284, during the administration of Doge Giovanni Dandolo, Venice followed and minted its first gold ducat with the same weight and finesse as the florin.

26

The gold ducats soon became the coins that defined value and took that role away from the silver grossi which were also minted in the city. Venice’s formidable fleet of ships, used for both trade and war, ensured the spread of the ducat throughout Europe.

The ducat became a European standard, understood and accepted everywhere, and an advertisement of the strength and power of Venice. A decree from the Venetian Senate in 1472 asserted that ‘the moneys of our dominions are the sinews, nay even the soul, of this Republic’.

27

The Zecca, the mint where all Venetian coins were cast, was at the city’s centre physically and politically. Sitting on the waterfront, the three-storey building stretched along St Mark’s Basin with entrances facing towards the doge’s palace. Each doge took great pride in the Zecca and its prodigious output of ducats, on which their image was struck. Here for over five hundred years, until the end of the Republic in 1797, the Venetian ducat was minted, retaining the same weight and purity as it had always done.

However, circulating among the fine gold ducats were forgeries and debased coins whose edges had been clipped. Clippers would remove small amounts of metal from the edge of coins, then melt the clippings down and sell the metal back to the mint. Counterfeiters would simply strike imitation coins made of a different, lower valued, alloy. Clipping and forgery began to undermine trust in the Venetian currency.

28

It became so prevalent that the Council of Forty, the supreme court of Venice, declared clipping a sin, abominable to God. Those men caught would be fined, have their right hand amputated and be blinded in both eyes. Women faced life imprisonment.

29

Venice was not the only place to have this problem. In Elizabethan England, coin clippers could be hanged or burnt alive, but these punishments did little to deter people. By 1695, in the reign of the Stuarts, counterfeit money accounted for around a tenth of all coins in circulation in England. It was mere chance whether what was called a shilling was really ten pence, sixpence, or a groat,’ wrote Lord Macaulay, the Victorian

historian.

30

The following year the Chancellor of the Exchequer appointed Isaac Newton to be the Warden of the Mint. Newton is best known for his falling apples and the laws of motion but from his time at the Mint he left behind a more tangible legacy: modern coins. The position was meant to be a sinecure, but Newton threw himself into the job with immense enthusiasm. As Warden, one of Newton’s roles was to enforce the law on crimes committed against the national currency. He became both a detective and a law-enforcement official, applying his scientific genius to the pursuit of London’s criminal minds. In an effort to foil the counterfeiters, Newton recommended that all England’s currency be replaced. Many older coins in circulation were worn down and thus easy to imitate. However, the Mint had developed a sophisticated new technology for inscribing the edges of gold coins with the words

Decus et tutamen

, meaning an ‘ornament and safeguard’. This inscription can still be found on the edges of British pound coins.

31

No seventeenth-century counterfeiters had the equipment to do this and so the Bank of England wanted to replace all the old coins with these newly protected ones. But Newton had an even more important reason for making and circulating new coins. For some time silver had been disappearing from England. Since lower denomination silver coins were needed to pay for everyday transactions, their disappearance was harming domestic business. Newton set about applying his great mind to this troubling economic problem.

Britain’s coinage system was suffering from a phenomenon called Gresham’s law: simply that bad money drives out the good money. The relative value of an ounce of gold to an ounce of silver was fixed by law at a level that made silver less valuable domestically than it was abroad. People could net a profit by melting silver coinage down and then selling it at a higher price on the international market. In this way silver, the ‘good’ money, was being driven out of the country. Lord Macaulay wrote: ‘Great masses were melted down; great masses exported; great masses hoarded; but scarcely one new piece was to be found in the till of a shop.’

32

Newton understood that mere laws would not be enough to stop the

smuggling of silver bullion abroad. He had seen how counterfeiters and clippers risked death for a quick profit. Rather, he recommended the obvious: that the exchange rate between gold and silver be set closer to that prevailing abroad, prohibiting anyone from paying or receiving gold guinea coins at a value other than twenty-one silver shillings. But the adjustment was not quite enough and silver continued to leave the country. Gold coins soon dominated and Great Britain found herself using a

de facto

gold standard, in which the standard monetary unit is defined by a fixed amount of gold. Newton’s miscalculation had raised gold to an exalted position; just over a century later, in 1816, the Bank of England introduced the British gold sovereign.

Like the Venetian ducat before it, the gold sovereign was the symbol of the world’s most powerful trading nation and became accepted globally as the safest currency. While living in Iran in the 1950s I remember travelling with my father to a remote village to buy a Persian carpet. After bartering with the seller, we drove away with three carpets, which are still on the floor of my house today, for the price of three gold sovereigns and an old suit. Even there in the middle of a distant desert, the value of the British sovereign was known and trusted.

The world’s dominant economy had moved on to a gold standard and other nations soon followed. The gold standard was introduced in Germany in 1872 following the Franco-Prussian War, and in Holland, Austro-Hungary, Russia and Scandinavia soon after. The Coinage Act of 1873 put the US on a

de facto

gold standard and France joined in 1878. By the early 1900s only China, parts of Latin America and Persia had not followed suit. These moves were made possible by the sudden growth in global gold reserves from new mines in America, South Africa and Australia. In the first six years of the Californian gold rush prospectors produced nearly US $350 million in gold (US $10 billion today). The discovery of this gold was the impetus to search for new mines across the world. Only sixty years after Marshall’s original find, world gold production had increased by one hundred times. Much as the rulers of Lydia and Venice had used a sudden influx of the precious metal to reform their currency system, the great new flows of gold across the globe were used to transform the international monetary system. That system brought many benefits to the nations who

were becoming more and more reliant on trade among themselves. This demanded stable currency exchange rates which were achieved by pegging each nation’s currency to a fixed amount of gold. Governments guaranteed that anyone could convert their currency back to gold and so the movement of different currencies between different countries was made possible. The international gold standard provided the security and stability needed for the globalisation of capital and trade. It also ascribed a price to gold that was fixed and immutable.