Serpents in the Cold (27 page)

Read Serpents in the Cold Online

Authors: Thomas O'Malley

|

|

_________________________

William J. Day Boulevard, South Boston

THE DAY PASSED

beyond the shuttered blinds but Cal was unable to move. He stared into the mirror above the bureau in Owen's guest room. At times he held his head in his hands and sobbed, and at other moments he raised his head and stared blearily before him. Then, in a matter of seconds, an indescribable desperation overtook him, a spiraling helplessness that threatened to choke him, and he felt that if he didn't act he might be buried alive. Panicked, he lashed out at the furniture. He swept the glasses and ashtrays off the bureau top, punched the walls, and finally shattered the mirror with his fist. He fell back on the bed screaming, clutching his hand, thin shards of glass embedded in his knuckles and blood streaming down his fingers and wrist.

Later he found himself on the floor, not knowing how he had got there. He had drunk too much whiskey, and was feeling dazed and unsteady. He was partially dressed but had stripped to his undershirt. His shoes were sodden and the bottoms of his pant legs were wet. Three new pint bottles glared at him from the bureau.

He fell asleep and then woke again and he was on the bed, the room darker now; thin bands of sunlight retreated to the floor beneath the window, shimmered at the edge of the shutters. The bedsheets were caked hard with blood. He flexed his fingers and pain shot up his arm and so he lay still again. He stared for a while at the ceiling, at the cracked plaster, and saw his and Lynne's bedroom ceiling with the water damage from when a nor'easter blew the shingles off the roof the year before, and he turned, imagining her there, smelling her skin, sensing the heat of her naked thigh stretched across his lower abdomen, the heady musk of her moist sex filling his senses, before he realized he was alone.

When he woke he was sprawled in the chair with his head bent at an awkward angle, the sides of his mouth wet with spit and drool. He reached for his drink, but after taking the first swig he began to cough, and soon he was doubled over on himself, falling out of the chair, gasping and shuddering and dribbling mucus on the carpet.

Lynne was standing a little way from him, twisting something in her fingers and looking out through the glass toward the distant, dark line of the sea. “Lynne,” he said tentatively. “Lynne?” And she turned and smiled at him with such openness and loveâof the kind he imagined was always there at the beginning of their marriageâthat his heart pressed achingly in his chest, and he held on to that smile in his mind, even as the figure before him swirled gray and faded before his eyes and he called out once more to the empty room. “Lynne?”

Sweating now from the alcohol in his blood, and clutching a pint of whiskey, he tottered out to the porch and collapsed into a chair covered in ice. But he was no longer drunk.

An overwhelming fear pushed him deeper into his chair and held him as he stared, wide-eyed and trembling, out onto the boulevard. Everything familiar was now hostile to him. The landscape of the neighborhood with all of its memories was a sort of ruse, taunting him with the power it held over him. Knowing he could never leave; knowing that, as Lynne had said so many times, he could never step fully out into the world and be free of it. She'd known the truth.

Â

DANTE STOOD BY

the window in Owen's living room watching the morning traffic on Day Boulevard, a few scraggly soot-colored gulls screeching as they fluttered above the rooftops, and the wind whipping the flagpole by the bathhouse. He was antsy but didn't know what to do. Cal was sleeping off a hangover in the other room, and he hadn't been in great shape when they'd talked earlier. He'd recited the events of the firebombing in a flat monotone, as if it were merely a recording, as if he were transcribing an event that had happened to someone else. It had been like talking to a stranger, and Dante didn't know if Cal had fully registered his being there. What he did know was that he was helpless in the face of such grief and of little help to Cal.

Owen's house was so silent he could hear the timbers creaking in the three-story frame. Not even a sound from the other tenants. He wished Owen would turn on the radio or the record player, anything other than the silence. But then, that's probably what Owen wanted. He was hoping the tension that inhabited the silence would get Dante going, start the need for a fix. When he turned, Owen, dressed in his police blues, was sitting on the sofa watching him. Dante knew he was waiting for him to speak.

“Well,” Dante said, “I guess I'll be going.”

Owen nodded, but kept staring.

“You got something to say, you should spit it out.”

“I'm just wondering how much more of you I can take.”

For Cal's sake, Dante ignored him. He wasn't going to fight with this asshole, not now. “When he wakes, tell him I'll stop by tomorrow.”

“What have you ever done for him but drag him down to your shit?”

“This isn't my shit.”

“'Course it is. You think Lynne would be dead if Cal hadn't gotten messed up with you and Blackie Foley?”

“Cal and Blackie have their own history that has nothing to do with me.” Dante picked up his hat off the side table, moved toward the door, but Owen wasn't done yet.

“When will he stop having to look out for you? When are you gonna start taking care of your own problems? I'm fucking sick of hearing that he's bailed you out again from the bookies or that he's spent the night searching the town's flophouses for you, worried that you might be dead. You've never given a shit what looking after you has cost him.”

Dante paused at the entrance to the hallway; he fingered the rim of his hat. “You're wrong. I know what it's cost him.”

“Well you don't act like it. Did you ever give a thought to what he lost over there? Huh? You think he was the same when he came back? While you were shooting up with all the town's lowlifes and faking a 4-F so you didn't have to fight, he was over there doing what you should have been doing.”

“I wanted to be over there fighting. They wouldn't take me.”

“It's always fucking someone else, isn't it? Always the dealer or your wife or the junk. You and your damn scapegoats. In all the years I've known Cal, I've never seen him blaming his problems on anyone else.”

Dante tugged the hat down on his head, raised his coat collar. “That's because he's a better man than I am, and a better friend. Tell him I'll see him tomorrow.”

_________________________

Forest Hills Cemetery, Jamaica Plain

NEAR DUSK DANTE

rode the El from one end of the city to the other and then back again, watching vacantly as the day began to darken and the cityscape seemed to change and alter itself beyond the windows as the first snowflakes came down like moths through the dark. They pattered against the glass before his face. He thought about the way Blackie's boys had killed Lynne and he imagined her burning alive, the pain she must have felt and the terrible slowness of it, and how Cal had seen her die like that. He thought of Owen's words, that he was a coward who had never taken responsibility for anything in his life, and the price that Cal had paid for his cowardice over the years.

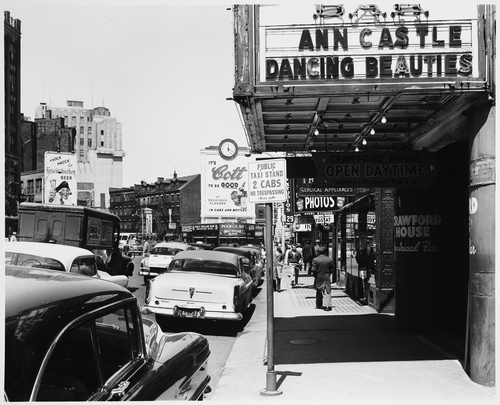

The train car rattled and pressed through the dusk light, and Dante looked down from the elevated tracks above Washington Street at the cars waiting below at the various intersections. Amber slivers of light showed from second- and third-floor apartments as they passed, so close it seemed he could reach out and touch them, their brick and stone and wood façades turned black by soot. Below, the homes and shop fronts drab and gray and crumbling, and to which only meager slants of sunshine showed themselves during the day. It was a part of the city the rest of the city had forgotten and would never remember again. The train's screeching brakes sounded out in the darkness, and electrical sparks showered down upon the world below.

At Forest Hills he finally roused himself. The train had reached the end of the line, and he stood and exited through the doors before the train headed back into town once more. He descended the ancient wooden escalator that clicked and clacked like a set of large revolving teeth, and through the empty station where his hard soles echoed on the brick floors, out onto the street, where the snow came down in big flakes that evaporated once they hit the ground. He crossed between the cars on Washington to a florist, bought a dozen white roses. It was all they had, and the petals had already curled, their ends bruised-looking and black.

On the corner by Kilgarriff's restaurant and the old apothecary a coal truck idled, swirling gray-black smoke churning from its exhaust. The driver, emptying coal into a cellar chute, cursed the cold as he rattled the stubborn metal swing arm encased in ice. Dante walked the length of Tower Street and entered the pedestrian gate and the cemetery's woods. His feet were already frozen, and he wished he'd worn another pair of socks. The path through the trees, slippery with the recent cover of snow, curved downward to the left, and he took each step cautiously.

The cemetery office, crematory, and columbarium with their backs to him were already closed for the day, the granite and puddingstone buildings dark shapes hulking at the main entrance beyond the Gothic gateway, the mullioned windows glowing slightly with a dim light from within. Briefly the peaked roof and stained glass windows of the Forsyth Chapel showed through the trees, and then he was angling eastward and through the woods again. The smell of brewing hops from the Haffenreffer Brewery half a mile away on Amory Street came to him on the frigid air.

The lamps had come on along the graveyard road, even though it wasn't fully dark yet, and as he walked the winding pathway through the grounds, their amber glow shimmered here and there upon the shoveled paths cutting between gravestones.

It was a large old graveyard, and it took a long time to reach Margo's grave. Along the VFW Parkway cars motored slowly and their headlights were small flickering embers through the ice-covered hedgerows and black tree branches.

Every time he visited he traveled a familiar path, past the crypts and graves of Revolutionary soldiers, politicians, statesmen, and he remembered when he and Margo used to visit the arboretum and Victorian gardens here in the summer months, along these same winding paths, surrounded by flowers then and rose bushes, and the pond with its two swans always coasting across the placid surface. He never imagined that he would end up burying her here, and he wondered if Sheila would also be here once the ground thawed so they could dig her graveânot in the same plot, for there was only one spot next to Margo, and he reminded himself that it was for him.

The path turned in to a grove, briefly illuminated by the glow of lamps, hazy amber orbs trembling through a brittle-looking latticework of leafless tree limbs, and then he was at her grave.

He glanced down at the flowers. The rose petals looked ghostly against the white snow at his feet. They appeared to have browned and wilted even more on his walk here. He wiped at his chapped lips with the back of his hand, knelt on one knee, and lowered the roses before the gravestone.

MARGO COOPER. OCTOBER 1, 1921â JUNE 24, 1950.

“I guess I'll never be able to pick you good flowers,” he said aloud, his voice cracking. “Always a little worse for wear. It's the thought that counts, you'd tell me, even if you were embarrassed to put them out in the vase.”

Raising himself back up, he brushed the snow clinging to his knee, flicked the smoldering cigarette back toward the path. He reached into his coat pocket and pulled out the revolver he had retrieved from his closet this morning after leaving Cal at Owen's. It was a gun he'd won in a card game years ago, the kind of game where everybody playing was broke and scavenged their meager belongings to put something, anything, on the table.

The only time he had ever pointed it with a target in mind was at himself. After a month at Mattapan State, he had returned to their bedroom for the first time since she'd died, and he had sat on the bed for hours, hunched over, elbows on his knees, head in his hands. He had tried his hardest not to think about it, to try and remember what the doctors had told him about coping with tragedy and moving on, but all he could focus on was where he was, sitting on their bed where the police had discovered him with his arms wrapped around Margo. It still felt as though it was all just a dream, a horrible dream. And that was when the idea had come to him.

He'd found the gun at the bottom of the dresser drawer, wrapped in a towel, and he'd gently slid the barrel over his bottom lip, pressed at his tongue, and eased his thumb over the trigger. He didn't know if there were any bullets in the gun, had no memory of ever loading the gun before. When he pulled the trigger and heard the dry click, it took him a while to realize the gun was empty, but still he pulled the trigger again and again. He'd eventually rewrapped the gun in the towel and put it back in the dresser drawer. It had been a rehearsal, but now he knew that he could do it if he had to.

A delicate wind came through the headstones, stirring up the fresh, unpacked snow, raising it up in the air and sending it drifting about his eyes, cooling his forehead, which was hot as if it were the focal point of the fever that gripped him. “I guess this is it,” he said aloud.

Bare branches swayed above him, scratching their crowded limbs against one another before the wind quieted and the branches suddenly stopped moving. A pressing silence followed, pushing at him and making him feel breathless.

He bowed his head and tried to finish a prayer to Margo, but nothing came to his mind except warbled melodies and lyrics of old songs that Margo used to sing to herself. He shut his eyes tightly; there was light coming through the darkness.

It was spring 1945, a month before the Allied victory in Europe. Margo sat at one of the tables spaced around the small dance floor of the Tap Room, wearing the blue dress he'd bought her on her twenty-third birthday. Her hair was done up in a victory roll, eyes shadowed with mascara, lips painted a cardinal red. At the other tables and along the bar, patrons were silhouettes and shadows. Their conversation carried on softly and out of range. Every so often he looked up from the piano keys, glanced at her, and smiled.

Most Tuesday nights she'd walk into the club halfway between his first two sets and sit at the same table. He would play all her favorites, one after the other. “An American in Paris,” “I Remember April,” and ending with “These Foolish Things.”

Midnight arrived, and the bar lights came on fully. People got up to leave, chairs scraping against the wooden floor. A teenage colored boy with a cigarette angled behind his ear came out with a broom and began to sweep the floor. At the table, Margo finished her whiskey sour, stood and fanned out the wrinkles in her dress, and then walked to the bar, asked the bartender for a last drink. Dante lit a cigarette, reached into the large brandy snifter he used for tips, and pulled out the dollar bills. He unfolded them, stacked them together, and began counting.

“Look at Rockefeller counting his money,” she said, and gently nudged his shoulder with her hip. He moved so she could sit beside him. She placed his drink, a whiskey with one ice cube, on the piano top.

“Have a drink and stop worrying about paying people back. It'll all work out.”

She kissed him on the cheek. And with her perfume lingering in his nostrils, a sweetly fragrant whisper in his ear: “Play for me, just one more song. One more song.”

Dante listened to snowdrift whisper along the frozen ground. Rheum dribbled from his nose and crept down to his upper lip. He reached up and rubbed at it with the cuff of his jacket. Off in the far distance a crow cried out, and farther off, a car horn blared impatiently.

He opened his eyes and wiped at them. “Sorry, Margo,” he said. “You don't know how sorry I am.”

Dante turned from the gravestone, walked back along the path into the woods. He slid the gun into his coat pocket, turned up his collar, and, holding his hat down against the wind, quickly walked an adjoining path toward the lights of Forest Hills, and as he moved farther away, only wishing he could turn around and say good-bye to his Margo one final time.