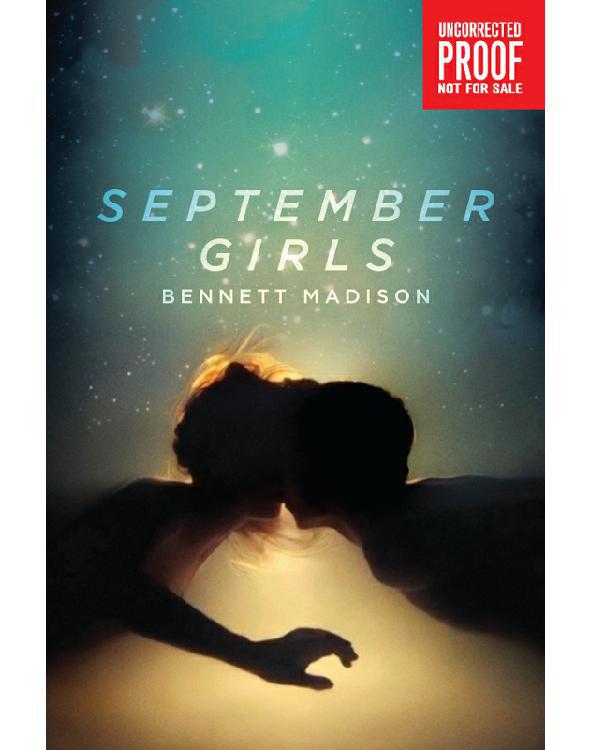

September Girls

Authors: Bennett Madison

Tags: #Legends; Myths; Fables, #Dating & Sex, #Adaptations, #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Issues, #General, #Fairy Tales & Folklore

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

Advance Reader’s e-proof

courtesy of

HarperCollins Publishers

This is an advance reader’s e-proof made from digital files of the uncorrected proofs. Readers are reminded that changes may be made prior to publication, including to the type, design, layout, or content, that are not reflected in this e-proof, and that this e-pub may not reflect the final edition. Any material to be quoted or excerpted in a review should be checked against the final published edition. Dates, prices, and manufacturing details are subject to change or cancellation without notice.

SEPTEMBER

GIRLS

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

Also by

BENNETT MADISON

The Blonde of the Joke

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

SEPTEMBER

GIRLS

BENNETT MADISON

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

Copyright

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

HarperTeen is an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

September Girls

Copyright © 2013 by Bennett Madison

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information address Avon Books, an Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

www.epicreads.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-06-125563-2

13 14 15 16 17 XX/XXXX 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

Dedication

For Kathryn Van Wert

SEPTEMBER

GIRLS

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

ONE

THE SUMMER FOLLOWING the winter that my mother took off into something called Women’s Land for what I could only guess would be all eternity, my father decided that there was no choice but for him to quit his despised job and take me and my brother to the beach for at least the entire summer and possibly longer. “A boy should go to the beach at least once in his life,” my father declared at the dinner table the night before our sudden departure. This edict was made in a decisive tone that I was more than familiar with by then—one that indicated he had no idea what he was talking about.

Dad had always been prone to vapid pronouncements of this sort, but in the aftermath of my mother’s disappearance, the habit had really gotten out of control. He was constantly inventing these half-baked bromides on the spot and presenting them as fact. The most obnoxious thing about them was their tendency to land on the topic of my supposedly impending manhood: that it was time to

be a man,

or

man up

, or

act like a man

, et cetera, et cetera. The whole subject was creepy—with vague implications of unmentionable things involving body hair—but the most embarrassing part was basically just how meaningless it all was. As if one day you’re just a normal person, and then the next—ta-da!—a

man,

as if anyone would ever even notice the difference.

Like you can just instantly transform like that. Like manhood is this distinct thing with actual markers and consequences. Well, maybe it is. But even if it is—if there is any person on this planet who actually knows what it means to

be a man,

anyone who could truly sum it up—I would guess my father to be among the very fucking last to have the tiniest clue.

And anyway! Now he was suddenly saying that a

boy

should go to the beach. Was this supposed to mean that I’d been given a reprieve from the expectation of manhood? If so, it felt like some small victory.

Jeff had the usual reflexive and halfhearted complaints involving his busy schedule and plans that couldn’t be rearranged. Dad’s scheme sounded fine to me. For one thing, it meant I didn’t have to bother studying for my pre-calc test, which was a task I hadn’t yet gotten started. For another thing, I was in the mood to go somewhere. Anywhere. Even if it was with my father and brother.

Dad didn’t even bring up the fact that I would be missing the end of school. He was apparently now beyond such petty concerns. I wasn’t about to argue. I just slid away from the table and went to pack my bags.

My father hadn’t been the same since Mom’s decampment. She’d left a few weeks after Christmas, and he’d spent the remainder of January as well as February and March in a swamp of discontent, drifting through the house silently, spending entire weekends on the couch, not looking up from his laptop, while I fended for myself and survived on a diet of Mama Celeste and Coca-Cola spiked with whiskey from the ever-dwindling liquor supply.

Looking back, it hadn’t been so bad. There are worse things than frozen pizza.

But by April the whiskey had run out (I tried to switch to Malibu, all that remained in the liquor cabinet, but it was disgusting), and Dad had bounced back with a vengeance. He took up

activities

: it seemed that if there was a tear-off sheet on a bulletin board in Starbucks he was willing to give it a try. He took piano lessons and joined a book club. He signed up for cooking class and became a charter member of a knitting circle–slash–men’s discussion group at the local library. Worst of all, he began wearing hats.

It was disturbing and bothersome. I quickly began to long for the days when I had been able to eat my pizza unmolested without Dad insisting on sit-down dinners in which he tried to entice me into joining him for things like his Gentle Yoga class. (“It’s all chicks,” he’d explained excitedly before his first session. But I’d begged off, and when he’d come home he’d been disappointed to report that all the chicks had been pregnant, except for one chick named Nancy, who was an octogenarian and whom I already knew anyway because she’d been my piano teacher when I was very little.)

Now Jeff was home from college, and my father, in his latest attack of enthusiasm, was taking us to the beach. All previous summers had found my family—often excluding Jeff, but always including the frumpy kindergarten teacher formerly known as my mother, now known as Artemis Something-or-Other—spending our cramped vacation weeks in various rocky, misty outposts on the dreary coast of Maine. The beach, yes, but by technicality only. This summer, Dad informed us, we would instead be traveling southward for the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Where the shore was sandy and the sun, so Dad told us, was actually sunny.

It struck me as slightly odd that Dad was so set on yet another beach as, for some unknown reason, he can’t actually swim. But I didn’t ask questions. It wasn’t any weirder than yoga.

When I stumbled down the stairs at five o’clock the next morning, still groggy and sour-breathed, I found Dad waiting by the door, already in his bathing suit and sunglasses, sitting in a folding beach chair, sipping from a thermos and reading a James Patterson paperback. Due to both his wild-eyed smile and the coffee-tinged scent of BO that wafted off him, I suspected he’d been up all night making preparations. “You ready to go, Tiger?” he asked, looking up eagerly.

I didn’t answer him. My name is Sam. The first thing you should know about me is that I don’t answer to Tiger.

Several hours later we were sitting in traffic on I-95 in the old Honda Accord, because my mother had naturally chosen the Volvo to abscond with. I was trying to ignore Jeff’s theatrical groans from the backseat. He had been out all night drinking with long-lost high school friends and was now curled up fetal and hungover with his face in a pillow, acting like a total baby in the customary way of older brothers. Next to me, my father was maddeningly oblivious to the gridlock as he whistled tunelessly, pausing every hour or so to make some remark about how now that our family was “all men” we could fart and scratch our balls without fear of female persecution.

Comments such as these were inevitably followed by loud farts.

My brother had managed to miss out on all the drama of the previous months by being away at Amherst. In fact, my mother hadn’t even said good-bye to him. (Her good-bye to me had been perfunctory and inadequate, but I gave her some meager credit for bothering.) And although Jeff had been naturally shocked to learn of the developments that had taken place in his absence, I didn’t gather that he was particularly upset by any of it. I guess he’d just been happy not to have to deal. After, Jeff called only infrequently to check in from school and seemed to avoid asking for any actual details on the situation for fear that they might prove unpleasant or—worse—demand action on his part. He ended every one of our exchanges with the same rushed and insincere “Hang in there, bro,” and

click—

then I was on my own again.

For hours on the way to the beach, Jeff snored and moaned fitfully while my dad honked and hummed and cursed traffic and strained to lure me into excruciating conversation, asking me about girls and school and needling me to try out for the track team in September and whatever whatever whatever.

Fuck you, Jeff,

I thought

.

My brother, having already managed to ignore the trouble of the year, was hanging on to ignorance for a few more precious hours. What a dick.

I know I must sound terrible myself—brittle and fussy and totally lacking in sympathy and complain, complain, complain. But I was at the end of my patience. Cut me some fucking slack.

At a certain point, after we’d been traveling for hours, I actually considered getting out of the car and just walking. Just taking off past the Dairy Queens and Waffle Houses and roadside farm stands and whimsically named convenience stores and pushing my way through the ribbons of trees bordering the roads toward an unfamiliar home. Perhaps I’d take a job as a carpenter or a welder. Something with my hands at any rate.