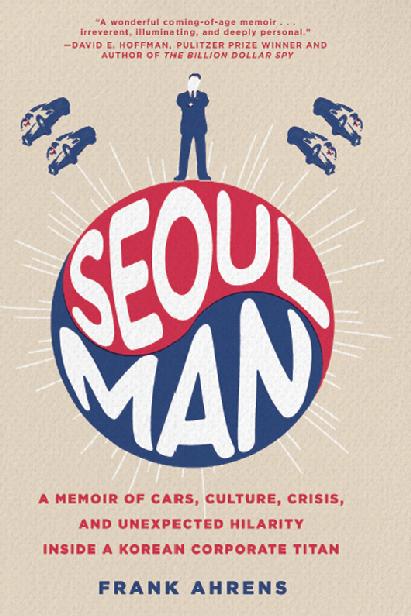

Seoul Man: A Memoir of Cars, Culture, Crisis, and Unexpected Hilarity Inside a Korean Corporate Titan

Authors: Frank Ahrens

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Business, #Business & Economics, #International, #General, #Industries, #Automobile Industry

Seoul Man: A Memoir of Cars, Culture, Crisis, and Unexpected Hilarity Inside a Korean Corporate Titan

Frank Ahrens

HarperCollins (2016)

Rating: ★★★★★

Tags: Biography & Autobiography, Business, Business & Economics, International, General, Industries, Automobile Industry

Biography & Autobiographyttt Businessttt Business & Economicsttt Internationalttt Generalttt Industriesttt Automobile Industryttt

Recounting his three years in Korea, the highest-ranking non-Korean executive at Hyundai sheds light on a business culture very few Western journalists ever experience, in this revealing, moving, and hilarious memoir.

When Frank Ahrens, a middle-aged bachelor and eighteen-year veteran at the

Washington Post

, fell in love with a diplomat, his life changed dramatically. Following his new bride to her first appointment in Seoul, South Korea, Frank traded the newsroom for a corporate suite, becoming director of global communications at Hyundai Motors. In a land whose population is 97 percent Korean, he was one of fewer than ten non-Koreans at a company headquarters of thousands of employees.

For the next three years, Frank traveled to auto shows and press conferences around the world, pitching Hyundai to former colleagues while trying to navigate cultural differences at home and at work. While his appreciation for absurdity enabled him to laugh his way through many awkward encounters, his job began to take a toll on his marriage and family. Eventually he became a vice president—the highest-ranking non-Korean at Hundai HQ.

Filled with unique insights and told in his engaging, humorous voice,

Seoul Man

sheds light on a culture few Westerners know, and is a delightfully funny and heartwarming adventure for anyone who has ever felt like a fish out of water—all of us.

**

Review

“Engagingly written and full of funny, intriguing probes into the quirks [Ahrens] discovers in his surroundings and himself. This is a nuanced look at a nation where an image of Western modernity is reflected and illuminated by an off-kilter mirror.” (Publishers Weekly)

“[Written] with humor and warmth… Amid the author’s personal journey reside priceless cultural and professional insights.” (Kirkus Reviews)

“Like Mark Twain in The Innocents Abroad, Ahrens gets good mileage out of his many gaffes as a naïve American bred to act quickly, blunder through problems and disregard authority… Seoul Man also looks into the history, culture, politics and business of the remarkable success story of modern South Korea.” (Shelf Awareness)

“If you have ever worked in a baffling alien culture or endured a family separation because of your job, you will probably enjoy this book... An entertaining read.” (Financial Times)

“Hilarious” (Unshelved)

“In this charming and affecting book, Ahrens finds out what makes this small but courageous country strive so relentlessly to be better. His portrait of Korea, the “shrimp between the two whales” of China and Japan, is filled with insights, youthful enthusiasm, and a zest for discovery.” (Tim Clissold, author of the international bestseller Mr. China)

“Lively, engaging and deeply personal, Seoul Man is at once a fascinating primer on the auto industry, a perceptive and often hilarious ex-pat adventure into “Koreanness,” and the story of an ordinary man transformed through faith and the power of love.” (-Brigid Schulte, author of the

New York Times

bestselling

Overwhelmed: Work, Love & Play when No One has the Time

)

About the Author

Frank Ahrens

was a reporter at the

Washington Post

for eighteen years before joining Hyundai Motor Company, where he eventually became a vice president. He lives in Washington, DC.

TO MY WIFE, REBEKAH,

AND MY DAUGHTERS,

ANNABELLE AND PENELOPE

CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- 1

ALMOST, NOT QUITE - 2

THREE MIDLIFE CRISES - 3

AT WORK: ALIEN PLANET - 4

AT HOME: ALTERNATE UNIVERSE - 5

DETROIT: SHOWTIME - 6

THE KOREAN CODES - 7

READING THE AIR - 8

CONSTANT COMPETITION - 9

ADMIRAL YI: KOREA’S GREATEST JAPAN FIGHTER - 10

SEJONG THE GREAT: GIVE-AND-TAKE WITH CHINA - 11

THE DANGEROUS COUSINS KIM - 12

“THIS DOESN’T RATTLE” - 13

THE CHAIRMAN ARRIVES - 14

SEOUL SURPRISES - 15

ALMOST, NOT QUITE ENGLISH - 16

CAR OF THE YEAR - 17

BYE, BYE, BABY - 18

NOT HERE, NOT NOW - 19

SANG MOO WAYGOOKIN - 20

THE 2013 MODEL - 21

GENESIS AND SONATA - 22

JAKARTA IS NO SEOUL - 23

ESCAPE PLAN - 24

THE JUDGMENT OF GENESIS - 25

FINDING HOME - EPILOGUE

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- CREDITS

- COPYRIGHT

- ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Punishingly peppy K-pop music pounded in my ears. Secondhand cigarette smoke filled my lungs; my crisp blue dress shirt was now soaked with my own sweat and splattered with beef drippings and mysterious sauces that had been served with dinner earlier in the evening. Flashing colored lights cut through the dark, windowless room I’d been packed into with a dozen yelling, clapping, laughing, hugging Koreans. A karaoke screen on a wall projected animations of saucer-eyed children and song lyrics in English and Korean. My wife must be somewhere in the room, but she seemed to have slipped just beyond my reach as I was jostled by the exuberant crowd that shout-sang along with the two Koreans sharing a microphone as some Korean pop tune played. When they weren’t shouting or singing, they were downing shots of whatever it was the older Korean ladies kept bringing in little green bottles. Drank, that is, whatever wasn’t spilled on the floor or on each other.

And here I was: sopping wet, laughing, singing incoherently and hugging people I’d met only five days earlier. Welcome to Korea.

I had expected South Korea to be more sterile. I’d had this feeling that South Korea existed thirty or so years in the future, where things are cleaner and more orderly, the way Japan used to seem. With its booming growth, strong democracy, ultrafast Internet, supersmart students, and all the sleek, impeccably groomed Koreans I saw using next-generation Samsung and LG electronics in the TV ads I watched online, South Korea turned out to be that, but it also turned out to be something else: a gritty, bare-knuckled uppercut to the jaw. The noise, the crowds, the traffic, the powerful smells, the nonstop visual stimulation—the all-night partying, the street protests, the fistfights in Parliament—all combined to stagger me on my feet moments after I’d stepped into the ring.

It’s a lot to process, so you have to start somewhere. If you’re going to talk about the way South Korea hits you, you must begin with

kimchi

. It insists.

You catch your first whiff before you’re outside Incheon International Airport, almost immediately after you deplane. To a Korean,

kimchi

smells like home. It’s the rocket fuel of their great leap forward, 150 years of industrialization pressure-packed into fifty years. To a foreigner,

kimchi

is at first only a smelly food, a pungent combination of fermented vegetables—cabbage, radishes, or cucumbers—and spices, chief of which is garlic. Traditionally made, it steeps in a jar buried in the ground for months, where its awesome olfactory power builds. Unleashed on every Korean meal, including breakfast, it stings the nostrils of the uninitiated, causing recoil. It comes in many types and doesn’t smell like just one thing. Some

kimchi

smells like cabbage, if the power of that cabbage were intensified a hundredfold. Some

kimchi

smells like vinegar and

chilies. Some

kimchi

has almost no smell. Some

kimchi

smells like feet.

Kimchi

exhaust—twenty people who just ate

kimchi

for lunch packed into an elevator, exhaling—has a metallic smell, a top note of iron filings that hits like an anvil and can induce a wooziness over the span of just a few floors. Today’s Koreans have separate

kimchi

refrigerators in their homes to isolate the aroma. Sure, it’s cliché to talk about the smell of

kimchi

, but to not do so would be to fail at describing an integral part of nearly every Korean’s daily life and an essential staple of their cultural identity.

Kimchi

is to Koreans what hamburgers are to Americans, only more so. Americans (most, anyway) don’t eat hamburgers with every meal.

Kimchi

is a reliable place locator. If someone blindfolds you and flies you to a mystery location and you get off the plane and smell a hamburger, you could be almost anyplace in the world. You get off the plane and smell

kimchi

, there’s a really good chance you’ve landed in Korea. If there were a global prize for a bona fide national dish and staple of cultural identity,

kimchi

would win it. Its smell is terrifically, aggressively, proudly Korean and probably the first bridge that foreigners must at least attempt to cross if they want to know something about this place.

My wife, Rebekah, and I arrived in Seoul in October 2010 after a thirteen-hour nonstop flight from Washington, D.C. (middle seats, middle aisle). Rebekah was about to begin a two-year posting in the U.S. Foreign Service at the American embassy in Seoul. I was to take over as director of global PR for Hyundai Motor Company. We had both left the

Washington Post

in Washington, D.C.

We had been married for only three months and were still getting to know each other and wedded life when Rebekah and I uprooted ourselves and moved to a foreign country, taking new jobs in new careers. I had left a steady twenty-one-year career as a journalist—the last eighteen years at the

Washington Post

—to

make one leap into public relations and another leap to living outside America for the first time in my life. Rebekah, the youngest child of a New Zealander Presbyterian minister emigrated to the U.S., had never spent eighteen years in any one place. A preacher’s itinerant vocation moved the family around in Rebekah’s youth and either instilled or complemented a restlessness that was already in her. Unlike most American kids, she was spoiling to see the world, and had already lived in China, Japan, Lebanon, and France before we met. For me, going to Korea was going to the moon. For her, it was just the next spot on an ambitious itinerary.