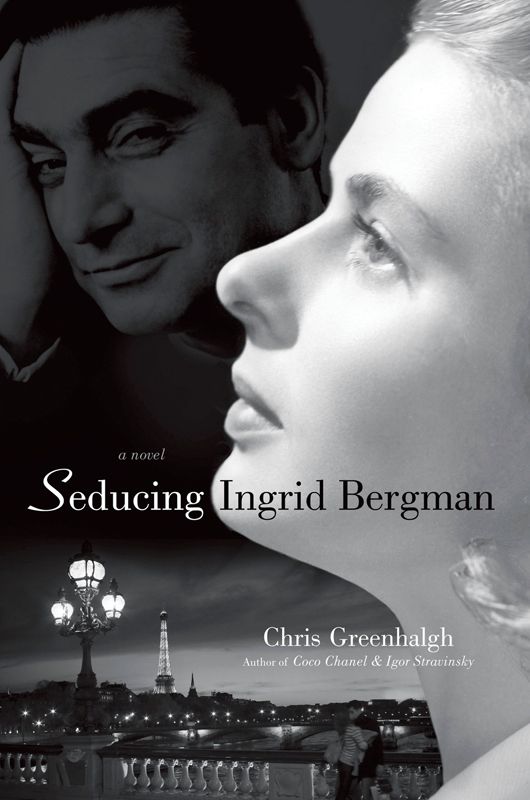

Seducing Ingrid Bergman

Read Seducing Ingrid Bergman Online

Authors: Chris Greenhalgh

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

1

A moment of trust. The green light flashes. There’s no time to think, and I don’t need to jump – the blast from the propellers just sucks me out of the hatch. Straightaway I’m falling with a splayed flailing of arms and legs, the roar of the transport lost in the swirling clouds above me.

I have a shovel in my backpack, a camera strapped to each of my legs and a flask in my breast pocket. Buffeted by cross-winds, my jacket puffs up. My cheeks feel as if they’ve been slapped and my hands smart from the cold. The air feels squeezed out of my lungs.

I’m hurled upside down, tumbled like a bird in a storm. My bowels turn watery. The contents of my stomach slide into my mouth – a nauseous mixture of coffee and whisky and scrambled eggs. My eyes prickle with tears. I manage to right myself. I count one thousand, two thousand, three thousand, and pull the cord. The parachute shuffles out of its pack and unfurls in an instant, blossoming into a silken basilica over my head. The plummeting sensation ends, and I’m conscious of a sudden weightlessness, swaying, my hands fastened to the straps.

A bent-winged gull hangs motionless, not caring that this is Germany or that we have crossed the Rhine. And for an instant it seems as if I’m not falling at all. Instead, I feel buoyed up, held steady by forces unseen. Purged of fear and boosted by a new energy, I seem – yes – I seem to be flying, flung upwards like a dove.

The ground spreads out like a map below: rectangles of newly ploughed land neatly organized in furrows, a few farmhouses and outbuildings, the fuzzy stuff of trees. I unstrap my Contax and take a few shots. No time for tricks, I just keep clicking. All around me, the men of the 17

th

Airborne Division twirl like sycamore seeds, their heads rubbing up against the webbing of their helmets and their last letters home. I feel a few drops of what I presume must be rain. But it’s not rain. Vapour condenses on the canopy and drips down onto my bare hands and face. The sensation is cold, my fingers numb. I’m careful not to let any moisture smear the lens.

Within seconds, everything changes. Bullets zing like hornets past my head. One punches a hole in my chute. I hear the snap of it against the fabric. I press my helmet down towards my chest, try to make myself small. I keep the Contax close to my face, still clicking. A chill spreads damply across my back.

It seems to take an age to reach the ground, though in reality it must be less than a minute. I think about a lot of things in quick succession – about the women I have loved and lost, about my mother having escaped the Fascists in Budapest, and about the fact that I am desperate to pee.

The paratroopers glide in slow diagonals. Most seem fine, but one is not so lucky. I can see from the trajectory that he’s headed straight for the powerlines. He must see it, too, as he drifts with dreamlike slowness, unable to change tack, prey to the direction of the wind. I want to shout out but there’s no way he can hear me, and nothing he can do. His body looks tiny. His legs wriggle in an attempt to veer off course, his arms yank at the straps, and at the last his mouth opens in a soundless cry as if this might lift him the extra few inches he needs to clear the wires. There’s a terrible inevitability about his path. He slides right into the dark lines, his parachute crumpling over the wires. He writhes frantically for several seconds, but strung like a puppet he proves an easy kill for the machine gunners. And he’s not the only one. Several others swing, stricken, fifty feet up in the leafless trees, their bodies dangling from their canopies, shrivelled pieces of fruit.

Is there a lonelier way to die?

Before I know it, the landscape enlarges, and there’s a high whistling noise. The wind stirs the tops of the trees. The ground seems to leap towards me. I realize that the small dark spot that has been bobbing about beneath me is my shadow and I rush towards it. I remember to keep my legs together. The harness bites into the top of my thighs. I hold on tight to the Contax and slam down into the earth. I feel the thud inside my lungs. Ngh.

I lie face down for several seconds, checking myself for injuries, registering a remote ache in my ankle, a jarring pain in my knee. I must have fallen awkwardly, but nothing is broken.

The earth is hard despite the thaw. A few scraps of ice still lie in patches, exposing the colour of my fatigues. I get up, my legs wobbly, and roll up the chute like a skin sloughed off. Immediately I look for cover. To my left lies open country. The nearest building, with snipers inside, is five hundred yards ahead. A stand of birches is about half that distance to my right. I suck air into my lungs and run – a zigzagging path, my shovel waggling in my knapsack, the camera banging against my chest.

I choose the thickest trunk I can find, check the focus on my Contax, crouch down and listen. The sound of rifle fire, flattened by the landscape, ricochets off the trees, so that at first I’m looking in the wrong direction. Dozens of crows explode upwards. Rounds of shelling shake the earth beneath my feet.

The light is ghostly between dark branches as I frame the shot, the sky thick with transport planes and parachutes still gliding like giant spores to the ground. My fingers are freezing, but my legs and back are slick with sweat. I’m thirsty, my throat parched, and now I feel really desperate to pee – partly from the cold, but also a sense of fear. My knee still hurts. A taste of metal enters my mouth, making me swallow.

Dead cattle and horses lie frozen in odd postures across the fields. The stench touches my nostrils, adds to the feeling of nausea. The sun is unlocatable behind the clouds. I finish one film, seal it in a canister, clip another one in, wind it on, snap the back of the camera shut, and start clicking again.

The resistance is fierce but limited, confined to half a dozen farm buildings and an outhouse. The artillery does its job. The buildings burn. The first prisoners are smoked out, hands on heads, the barns mostly destroyed. The inner walls are exposed so that it’s hard to believe there were people in there just a few minutes ago, and odd to see how small a space the rooms once occupied. The farmers are the last to flee – an old man with expressionless eyes, his headscarved wife rescuing what possessions she can, and their grandchildren, a boy and a girl, too paralysed with fear to cry.

By 11 a.m. I have several rolls of film, including shots of parachutes slung over wires like stockings over a bedpost, medics tending to the wounded, and a transport plane bulking large and coming in low over the trees. I write

March

1945

on the canister. A good morning’s work. Time for a cigarette and a hit of whisky from the flask.

And only now does it seem safe to pee. I dream of trees in leaf, fields ripe with wheat, an eight-page spread in

Life

, my pictures showing the world what happened here near Wesel. As the beatific vision continues, I imagine myself in the arms of a good woman, who strokes my hair and covers my face with lipsticked kisses, making everything all right.

The reverie doesn’t last long. The tree I relieve myself against has only just started to darken when I see the sign: ACHTUNG! MINEN!

I spend the next four hours until the disposal team arrives standing motionless, smoking cigarettes, checking the focus on my cameras, doing my best to look unconcerned.

* * *

She almost ceases breathing, pulls her stomach muscles in, resists the impulse to fiddle with an earring. But she can’t stop her mind racing or ignore the itch inside her, the little kick of ambition that drives her on.

Does she think she’ll win? She can’t think that far ahead. Does she deserve to? That’s a different question.

She tries to slow down the pounding of her heart, works to control her breathing. Everything around her grows quiet. She hears the nominations read out by last year’s winner, Jennifer Jones – her own, followed by Claudette Colbert, Bette Davis, Greer Garson, Barbara Stanwyck – each name announced with the same crisp excitement that holds out the promise of brilliant things. Like snow, she thinks.

There’s a silence. An envelope is opened, its rustle amplified by the microphone that stands like a sunflower in the middle of the stage.

She holds her husband’s hand to the left and feels the tightening grip of her producer, David Selznick, to the right. The room pitches. She finds it difficult in this instant to make connections between things.

When the four Scandinavian-sounding syllables of her name are announced, they seem remote, oddly foreign, unrecognizable. Applause fills the auditorium at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, quickening around her.

‘That’s you,’ Selznick says. ‘You’ve won. You’ve won!’

‘Go get it,’ Petter says.

Ingrid stands and the seat tips behind her. Everything is confusion: the sudden tumult of the music, the fan of lights, the fierce clapping and chasing spotlights.

She presses her neck forward, her senses alert, her eyes alive to the male attention that swims around her. It is harder than she imagines to walk in a straight line. Caught in a current of affection, she feels tugged along, her insides filling with warmth. The sensation enlarges. Her hands grow clammy and, as if she’s had a glass of wine already, she feels the redness creep into her cheeks.

Photographers jostle and flashbulbs explode, capturing the evening in bright slices. Hatless, simply dressed, with a long beaded necklace that hangs down to her waist, in flat shoes and wearing minimal make-up, her effort at restrained elegance feels inadequate set next to the dinky hats and spotted veils of her fellow nominees. For a moment, she feels horribly exposed.

Unknown in Hollywood just six years ago and speaking with an accent that was mistaken for German as the war began, Ingrid still feels an outsider. But she got lucky with

Casablanca

, made her mark in

For Whom the Bell Tolls

, and here she is lauded for her performance in

Gaslight

, with

Saratoga Trunk

and

Spellbound

about to open in theatres across America, and shooting

The Bells of St Mary’s

for a Christmas release.

Later she will regret that the evening went so quickly, that the moment like a dream was over so fast. Later she will feel cheated by the experience, and long to relive it. But in this instant, she almost runs onto the stage.

She remembers thinking it important to keep her head still. After that, everything is a blur. She remembers taking a breath to steady herself. If she remembers hovering over the microphone, it is only because of the lights splintering into a million filaments. If she recalls being conscious of the audience, their faces grey beyond the glare, it is only because of the collective hush.

‘I’d like to thank the Academy for honouring me with this award.’

The microphone picks up a slight tremor in her voice, but the note is huskily feminine, not girlish, and noticeably lower than that of Jennifer Jones.

Her fingers play with the statuette, her palms mottled, her hands surprised by how heavy it is. She feels the tug of it like a gravitational force, clings to it, enjoying the sense of possession.