Secrets of Your Cells: Discovering Your Body's Inner Intelligence (24 page)

Read Secrets of Your Cells: Discovering Your Body's Inner Intelligence Online

Authors: Sondra Barrett

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Each gene reveals a different “packet” of encoded information necessary for your body to grow and work. Structural genes contain the recipes for how you look: the color of your eyes, how tall you are, the shape of your nose, the red protein hemoglobin, the keratin of your hair, the collagen in your skin, and more. Regulator genes tell the cells when to grow and when to stop growing. They also include the stop/start genes that indicate the beginning and end of a particular sequence of information. And yet, in the human genome, 98 percent of the genetic material has no apparent function; only 2 percent of our genes hold codes for all our proteins.

3

In the past, the non-coding genetic material was called “junk DNA”; now scientists are beginning to study what the rest of our genetic script does.

All cells in your body contain the same DNA and identical genetic information. Mature red blood cells are the exception: since they have no nucleus, they have no DNA. Only when immature red blood cells are developing in the bone marrow do they contain a nucleus.

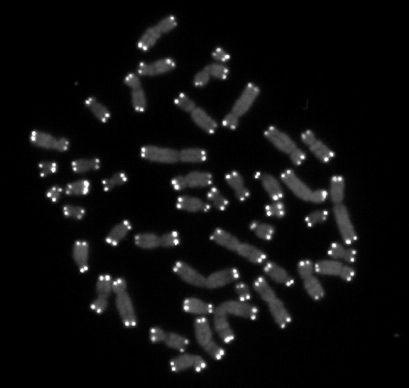

Genes are packaged at specific locations in structures called

chromosomes

(see

figure 6.2

). You might think of genes as all the entries in the entire phonebook, while the chromosomes represent a single page. The genetic code represents the words on the page.

Chromosomes are long strings of genes. The cells within the human body contain forty-six chromosomes. Our chromosomes come in pairs, and so do our genes: half come from Dad and half from Mom. We actually have twenty-two pairs of what are called autosomal chromosomes (non-sex chromosomes) and a pair of sex chromosomes that determine our gender: the X and Y genes.

4

A female will have two X genes, while a male has an X and a Y. When a cell starts to divide, the chromosomes organize themselves along the center of the cell to be duplicated and shared between the new cells.

Figure 6.2

Forty-six human chromosomes with the telomeres appearing as bright dots at the ends of each chromosome; image by Hesed Padilla and Thomas Reid

METAPHYSICAL SECRETS IN OUR CELLS

Sacred Numbers

If you are intrigued by numerology, you may be surprised to learn that the number twenty-two is represented by the number of pairs of human autosomal chromosomes. In the divinatory tarot, twenty-two is considered a master number and is reflected in twenty-two cards of the major arcana, each of which represents a significant symbolic step along our life journey. There

are also twenty-two letters in the Hebrew alphabet. You’ll find more about sacred numbers in

chapter 8

.

5

DNA and Its Divine Designs: Molecular Monogamy

Long strands of DNA are segmented into single genes that provide the blueprint for a specific protein.

6

Each DNA thread wraps around its complementary twin, creating DNA’s distinctive double-stranded spiraling shape (see

figure 6.3

). To envision what DNA looks like, imagine two long threads coiled together in a double helix, like a twisted rope ladder with rigid rungs. One rope carries the code; the other strand complements it, acting as a kind of keeper and protector of the whole. Double-stranded molecules are much harder to destroy than a single strand. When a cell begins to reproduce, the DNA must be duplicated. To accomplish this, the two strands unwind and each serves as a template for a new double-stranded DNA.

The spiral is an efficient, compact way to safely store the astonishing amount of information the nucleus contains. The stretched-out DNA from one person is billions of miles long. How do we know that? Each human cell has around six feet of tightly coiled DNA, and if we estimate 10 trillion cells in an average person, that means that if we unwound all of that DNA and laid the strands end to end, we’d get around 60 trillion feet or about 11 billion miles of DNA. Your DNA could stretch from here to the sun and back at least sixty times! The Bible talks about Jacob’s ladder stretching between earth and heaven. When Jacob dreamed of this ladder, was he seeing the spiral staircase of DNA? The ladder image holds great symbolic meaning for Jews, Christians, and Muslims, a connection to God and the spiritual path. And since we know one person’s DNA could reach to the “heavens,” perhaps this is another example of sacred secrets hidden within our cells.

Since DNA is a blueprint, its design must be precise. It is constructed from four molecular building blocks called nucleotide bases. The names of these bases are adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). (The letters are used as shorthand to write out the genetic code.) The order of the bases along the strand of DNA carries the encoded information.

Figure 6.3

Spiraling DNA; the lines connecting the two strands represent the bonds between the nucleotide bases

Here’s another example of chemical complementarity: the building blocks are “monogamous”; each base can partner with only one other. Where there is a T on one strand, its partner on the other strand must be A; where G is on one side, its partner must be C. There are no exceptions to this exclusive union. Pairing with the wrong partner signals the need for separation and calls into play a potent repair system to separate the ill-suited partners. An advantage of such specific partner links is that it permits rapid detection of any mistake. With a partner error, there’s a “kink” in the regular undulating spiral architecture of the DNA, and this triggers repair genes to come to the rescue. Molecular monogamy and the architectural helical design help ensure the integrity of our DNA.

The Code of the Winding Staircase

If you picture DNA as a winding ladder, you can see how one side of the staircase must perfectly match and complement the other. The sequence of the bases on one strand holds the genetic instructions. Its protective partner strand holds the complementary sequence.

Let’s look at an imaginary genetic sequence: ATAGGCTTT. Its complementary partner would have to be TATCCGAAA (remember the monogamous relationship). The divine wisdom of nature rules how the two strands are linked.

The entire genetic library of this world . . . the structure of every living thing is reducible, ultimately to these four. . . . a very simple code but a very long message.

— CARL DJERASSI

The Bourbaki Gambit

The same four bases that encrypt the genetic code—A, T, C, G—appear throughout the living kingdom.

7

Whether a bee or a hippo, an oak tree or a mosquito, everything on this planet uses the same encoding system; it’s only the arrangement of the letters that distinguishes man from mouse. Though the computer holds its vast information in a binary code of 0s and 1s, the more complex DNA code is made of three units called triplets or codons. These encoded base letters signify which of the twenty amino acids is to be used in the building of proteins. There are sixty-four possible combinations of the three letters; all sixty-four are assigned either to amino acids or to start/stop signals. Imagine reading a hodgepodge of letters that encode specific information. You would have to know where to start reading the code and where to stop.

The sequence of these three-letter codons along the gene strand enables the cells to assemble amino acids in the correct order to construct strands of protein or a polypeptide (a small protein).

Here is the three-letter breakdown of a piece of DNA reading AAAATGCGTTCG.

Snippets of this code: | AAA | ATG | CGT | TCG |

The complementary strand: | TTT | TAC | GCA | AGC |

A complementary strand with errors: | GTT | TGG | GCA | AGA |

The universal nature of the genetic code means that each species treats any new DNA as its own, generating millions of copies of these genes. In fact, one way viruses do their damage is to inject their genetic material into living cells and voilà—our own cellular machinery copies their genetic information and makes new viruses.

METAPHYSICAL SECRETS IN OUR CELLS

Sacred Codes

Our cells reveal another cosmic “coincidence.” Like the genetic code of triplets and sixty-four possible sequences, the ancient divinatory system of the

I Ching

depends on a coding system of trigrams: combinations of three different solid or broken lines (see

figure 6.4

). Trigrams, a group of three letters or lines, provide for sixty-four possible combinations. Both the genetic code and the I Ching present sixty-four combinations. Once more we have an ancient metaphysical system that could be interpreted as mirroring what takes place in our living cells. Both systems, cellular and metaphysical, reflect change.