Secrets of Your Cells: Discovering Your Body's Inner Intelligence (11 page)

Read Secrets of Your Cells: Discovering Your Body's Inner Intelligence Online

Authors: Sondra Barrett

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Who Am I?

To give you examples of all the ways we can recognize the self, here are some of the ways I answer the question “Who am I?” I am atoms, molecules, cells, thoughts, feelings, ideas, Sondra, daughter, mother, grandmother, friend, lover, work, spirit, love, sound.

In terms of metaphysical and symbolic traditions, from astrology I am a Libra-Scorpio; from tarot and numerology, the priestess, justice, an 11 and a 2; and from another metaphysical system, I am the queen of hearts. Consider: If one ascribes to metaphysical qualities, how do they add to our identity and life purpose? Where do such mythic or esoteric labels support, enhance, and expand our self-identity?

BODY PRAYER

Anchoring—A Declaration of Self-Creation

The following exercise can help you gain a solid sense of self and serve as a tool for intentionally creating and re-creating the self you want to be.

Choose a place that feels like a sanctuary for you. Take a moment to “get there.” Then say a few words, silently or aloud, to thank your cells and the great mystery for all that you are, have, and know.

Feel your feet on the earth, grounded and anchored. You can gain strength from the earth’s energy when you feel your feet upon her. You can also imagine that your head is connected by an invisible cord to heaven. Rock a bit back and forth on your feet until you feel solid on the ground.

Imagine you are a rope held between the earth and the heavens. Make circles with your waist, rotating belly and hips, moving slowly as you would with a hula hoop. Your shoulders remain parallel to the earth while the middle of you leads the motion. Move like a rope being held at both ends. Continue until you feel anchored. Then change direction. You may discover that circling in one direction feels easier and more natural than the other. Which way is more comfortable for you? Now add the humming sound “mmm” as you root and spiral, connecting to the earth and your cells. Stay with this for a few minutes.

Now, firmly rooted on the earth with your feet anchored, raise your arms to the heavens, flexing your hands at your wrists. Touch your hands to your heart and belly and then bend down to touch the earth. Do this at least three times.

Make this a prayer of intent. When you raise your arms, ask for guidance or what you need to know to take your next step in life. Or, as you reach up, give gratitude for all that you are and have. When you touch your belly and heart, you commit to your intention or your higher self. As you reach to the earth, you plant your prayers of intent, perhaps saying aloud that you’ll do whatever it takes to make this seed grow.

When you become rooted and enact the three movements, you are in essence declaring an act of self-creation.

Toward an Integrated Self

We began this chapter by examining an almost universal religious statement: I AM THAT I AM. Now let’s revisit that idea as we might find it in our daily lives.

Our cells, when they are healthy, know exactly who they are, while our psyche may consider the question in an ongoing fashion: “Who am I?” “Who am I now?” As we journey toward maturity and transformation, accepting who and how we are in the moment takes us to a deeper appreciation of I AM THAT I AM.

Acceptance is part of our human recognition of self.

Recently a student called me to share her revelation about her cells and self. Her walk one morning was particularly difficult. It was literally an uphill battle for her and her cells. She told me that on the steep trek her cells were screaming, feeling stretched to their limit; they hurt and wanted to stop. Then her consciousness (what I’ve been calling mind and psyche) revealed its role in the walk: we all benefit if we go past the struggle to reach the top of the hill. That’s when she understood the collaboration between cells and consciousness, matter and mind. The cells can do their thing unaided by mind, yet when the mind accepts how it is and says let’s go a little farther—let’s not quit yet—the entire being benefits, cells included. The struggle adds to a new sense of self.

When we accept and acknowledge that our choices influence our cellular health, we can embrace our cellular nature as a sacred chalice or vessel we have been given to take care of, to nurture. We know that we are one.

In the next chapter you will discover how our consciousness sends messages to each cell and how cells engage in conversations with one another.

Chapter 3

Receptivity–Listen

Our smooth-muscle cells . . . work away on their own schedules . . . opening and closing tubules according to the requirements of the entire system. Cells communicate with each other by simply touching; all this goes on continually, without ever a personal word from us. The arrangement is that of an ecosystem.

— LEWIS THOMAS

The Lives of a Cell

A

s we continue to explore the divine nature of our cells and ourselves, in this chapter we move from “me” to “we.” Our cells have much to teach us about perceiving one another, listening, being heard, and the value of connection. And how our cells “listen” is through receptor sites or “antennae” on their outer surface.

Cells Talk

If we were able to listen to our cells’ conversations, do you think they would be talking about how to wrangle a raise at work or who did better on an exam? No! We’d hear them discuss moving faster or slowing down,

breathing a little more deeply, pushing forth and pulling back. We’d hear them ask, “Which message shall I respond to?”—there are so many.

The better we understand how our cells manage our ever-changing internal, alchemical environment, the better will be our relationships with ourselves and each other. And the greater appreciation we will gain for what magnificent creatures we are.

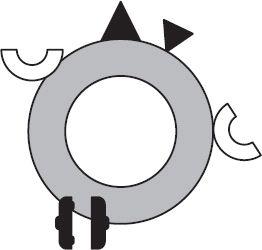

Again, as in the two preceding chapters, we begin with the surface of the cell, the membrane (see

figure 3.1

).

We have learned that the cell membrane carries distinguishing marks revealing its own nature—I AM. The membrane also holds the ability to communicate with other cells. Communication depends first on the membrane’s antennae or receiving sites (receptors), which have the uncanny ability to recognize specific incoming molecules. If the molecules are a good fit, our attentive cells will embrace them. This is similar to the design requirement for the immune collaboration between antigens and membrane receptor sites described in

chapter 2

; cells use the same mechanism to recognize molecular messages from a changing environment. Nobel laureate Christian de Duve has named this phenomenon

molecular complementarity.

1

Figure 3.1

Diagram of cell with self markers (triangles) and different receptors (the other shapes)

Biological information transfer is based on chemical complementarity, the relationship that exists between two molecular structures that fit one another closely—a dynamic phenomenon as the two partners are not rigid. When they embrace, they mold themselves to each other to some extent. Embrace leads to binding.

— CHRISTIAN DE DUVE

Vital Dust

What messages must our cells attend to? Chemical signals of danger, a need for new resources or energy, speed up, slow down—there are molecular messages to rest and relax, renew resources, and recycle. Because of instantaneous recognition, our cells can respond in nanoseconds to keep us protected, moving, and replenishing. But how?

The Receivers

Each cell’s surface is studded with thousands of receptor sites whose function is to detect information essential to its survival. Any given receptor is shaped so that it can only accept certain messages. The same lock-and-key analogy we have seen before applies here as well; only if a cell has a receptor able to recognize a particular chemical signal can it respond. This boils down to both the receptor and the initiating message having the correct spatial, geometric, three-dimensional structure relative to one another. Some scientists say that the vibrations of each—receptor and message—also play a part in this dynamic conversation. The receptor is not fixed; it molds itself around the message, holding on.

Recall that the cell membrane is made up of a double layer of fats. These are called phospholipids, and they merge to form what we can think of as a stable “soap bubble.” The protein receptors float in this lipid surface layer while some of them straddle the membrane as many as seven times, touching both outside and inside the cell. The receptor grabs its matching molecule from outside the cell with its “hands” and then moves its “feet” on the inside to tell the rest of the cell that a message has been received. The cell can respond to the message, provided that all the other necessary mechanisms

inside

the cell are engaged

and turned on. This involves a

conformational

change in the physical structure of the receptor—that is, the receptor

changes shape

when it contacts a molecule it recognizes. In

The Biology of Belief,

Bruce Lipton writes that this membrane activity constitutes the brain of the cell. Yet cellular intelligence requires much more than membrane receptors, something you will learn more about in the next chapter. The ultimate aim of a molecule binding to its receptor (if molecules have goals) is to turn the cell on for a specific activity. Examples of cellular activities include making more energy, slowing down, and contracting. You can envision the interaction as a molecular embrace: the receptor has to “hug” the signaling molecule. If the squeeze is too tight, the “on” switch may stay on too long; if it’s too loose, the cell might not even know it’s supposed to do anything. It’s the “just right” connection that encourages the cell to change what it’s doing and take a different action.

One of our first insights into the importance of cell receptors began around sixty years ago when researchers examined how adrenaline works. Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a molecular signal of distress that tells our bodies to get ready for action. It ensures that there is enough sugar in the blood to keep things going by facilitating liver cells to free glucose from its storage form, called glycogen, and release it into the blood. Stress (the fight-or-flight response), which can be triggered by an acute physical or mental challenge, creates a chemical drumroll that moves energy to our muscles, increases blood pressure to get oxygen to the cells, and accelerates everything needed for immediate survival. If the cell receives a message of danger, it enables us to fight or run away. Almost every cell type in the body has receptors for adrenaline, though each responds in its own specific way. Heart cells beat faster in the presence of adrenaline, while cells in the pancreas stop secreting insulin. Every part of us has a job to do to deliver us from danger.

2

To give you a sense of different receptor shapes, compare the form of adrenaline (see

plate 8

in the color insert) to the form of caffeine (see

plate 9

in the color insert). You can easily see that cells need different kinds of receptors to respond to the diversity of chemicals.