Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld (20 page)

Read Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld Online

Authors: Linda Washington

BOOK: Secrets of the Wee Free Men and Discworld

6.86Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Time Waits for No One

If you were in, say, Armethalieh in Mercedes Lackey/James Mallory's Obsidian Trilogy series, you'd measure time by bells (“See you in half a bell, dude”), specific days (Light's Day), or by wars and epochs (the time of Great Queen Vielissiar Farcarinon; the Great War). In other fantasy series, time is regulated in a similar way (the Third age of Middle-earth and the calendar according to the “Shire-reckoning” of Tolkien's

Lord of the Rings

).

Lord of the Rings

).

In our world, we measure time by ages and eras (Ice Age, Napoleonic era, Victorian era), the Gregorian calendar (rather than the Julian calendar named after Julius Caesar), B.C.-A.D. demarcations (thanks to Venerable Bede, an eighth-century monk scholar who first used A.D.), and by how long we have to wait in line at Starbucks or the grocery store (“That took ages!”).

In Discworld, there's a hodgepodge of ways to measure time.

Calendars and Almanacs

Societies of our world have differing calendars (Gregorian, Hindu, Chinese, Japanese) in which the names of months or even the number of days in a month vary. But in a place like Discworld, where centuries and years are marked by animals, food items, or inexplicable terms (the Century of the Fruitbat, the Year of the Intimidating Porpoise, Century of the Anchovy, the Year of the Impromptu Stoat, Third Ning of the Shaving of the Goat), and the months have such names as Grune, Ick, Spune, and Offle, you've got to expect some weirdness.

The naming of years and centuries in Discworld reminds us of the Chinese calendar, a calendar with a sixty-year cycle based on the moon phases, the sun, and conjunctions of planets. As you know, in China the years follow a cycle of animal names (year of the dragon, year of the ox). You've probably seen a chart of them on a placemat wherever you go for dim sum. And although some of us born in years like the year of the rat could wish that the year bore the name of a cooler animal (such as the year of the tiger), it certainly beats being born in the Year of the Impromptu Stoat.

Terms like the Third Ning, although made-up, remind us of the different dynasties in the history of Chinaâpart of the era/epochbased way of measuring time.

You probably know a year in Discworld can last for eight hundred days and runs through eight seasons, rather than the usual four. (If you don't know, you do now.) Imagine what you'd do with all of that time. Take two summer vacations?

Almanacs also record the moon phases.

Poor Richard's Almanack,

developed by Benjamin Franklin, lists the times of sun and moon risings and planetary configurations. In Discworld (especially the Chalk and the Ramtops), an annual almanac called the

Almanack And

Book Of Dayes

(

Equal Rites, Lords and Ladies, The Wee Free Men

) is used to gauge the weather and serves as bathroom tissue. Quite handy.

Poor Richard's Almanack,

developed by Benjamin Franklin, lists the times of sun and moon risings and planetary configurations. In Discworld (especially the Chalk and the Ramtops), an annual almanac called the

Almanack And

Book Of Dayes

(

Equal Rites, Lords and Ladies, The Wee Free Men

) is used to gauge the weather and serves as bathroom tissue. Quite handy.

Holidays and Special Days

Our holidays and special days tell us a lot about who we are as a people and what we believe in. We celebrate Hanukkah, Christmas, Kwanzaa, Martin Luther King Day, Kasmir Pulaski Day (a Chicago holiday), New Year's, Groundhog Day, Valentine's Day, and hold events like Oktoberfest and elections. In Discworld, they also celebrate New Year's, along with such holidays as Hogswatch, Soul Cake Tuesday, and Fat Lunchtimeâlike Fat Tuesday in our world. And then there are Troll New Year, Chase Whiskers Day, and Sektoberfest, a two-week event involving a beer festival, like Oktoberfest. Pratchett describes these and other holidays in

Terry Pratchett's Discworld Collector's Edition 2005 Calendar

and

Discworld's Ankh-Morpork City Watch Diary

.

Terry Pratchett's Discworld Collector's Edition 2005 Calendar

and

Discworld's Ankh-Morpork City Watch Diary

.

In Discworld, certain rituals help mark the seasons, holidays, and such special occasions as weddings. There's the Morris dance, which comes from the traditions of the British Isles. In our world, the Morris is danced at the beginning of spring and summer. It's been around since at least the fifteenth century. Seven dancers, usually male, wear white clothes, bells, and clogs. In

Wintersmith,

the usual Morris dance occurs in May, to usher in the summer; and in

Reaper Man,

it ushers in the spring. As we mentioned in

chapter 5

, Jason Ogg and Lancre Morris men gather to dance for the king's wedding on Midsummer's Eve. But then there's the Dark Morrisâa Pratchett creation. Danced without bells, it ushers in the winter in

Wintersmith.

Wintersmith,

the usual Morris dance occurs in May, to usher in the summer; and in

Reaper Man,

it ushers in the spring. As we mentioned in

chapter 5

, Jason Ogg and Lancre Morris men gather to dance for the king's wedding on Midsummer's Eve. But then there's the Dark Morrisâa Pratchett creation. Danced without bells, it ushers in the winter in

Wintersmith.

The Time of Your Life

Another way of measuring time is by the lifetimerâthe hourglass that measures a life. Death carries one for each person he visits who is about to die. The lifetimer is a symbol of the mortality of man. As the Romans would say,

“Memento mori”

â“Remember that you are mortal.” This is reminiscent of the grim reminder of mortality in Genesis 3:19, “For dust you are and to dust you will return” (New International Version). But the lifetimer used by Wen the Eternally Surprised (for more on him, keep reading) in

Thief of Time

grants time to the person to whom it is given.

“Memento mori”

â“Remember that you are mortal.” This is reminiscent of the grim reminder of mortality in Genesis 3:19, “For dust you are and to dust you will return” (New International Version). But the lifetimer used by Wen the Eternally Surprised (for more on him, keep reading) in

Thief of Time

grants time to the person to whom it is given.

The Discworld Time Lords: The Monks of History

If you're a fan of the

Doctor Who

TV series, one that has been around since the 1960s, you know that the Doctor is a Time Lord from Gallifreyâsomeone able to travel back and forth through time. He's the last of his kind. So, why'd we bring him up? Because of the Monks of History in Discworld. They are time lords, in a wayâthe ones who monitor and shape time. Their existence is top secret. But the people of Discworld feel the effects of their constant vigilance. (Maybe you're thinking of the Men in Black right about now ⦠)

Doctor Who

TV series, one that has been around since the 1960s, you know that the Doctor is a Time Lord from Gallifreyâsomeone able to travel back and forth through time. He's the last of his kind. So, why'd we bring him up? Because of the Monks of History in Discworld. They are time lords, in a wayâthe ones who monitor and shape time. Their existence is top secret. But the people of Discworld feel the effects of their constant vigilance. (Maybe you're thinking of the Men in Black right about now ⦠)

In the creation of the Monks of History, you can find a hint of Eastern religions. There's the great Lu-Tze the Sweeper, a follower of the Way of Mrs. Marietta Cosmopolite and master of déjà fuâusing time as a weapon, rather than, say, kung fu. Lu-Tze, who appears in

Night Watch, Thief of Time,

and

Small Gods,

reminds us of Zen master Lao-tzu, writer of

Tao Te Ching,

and blind Master Po, the Shaolin monk who trained Kwai Chang Caine in the 1970s TV series

Kung Fu.

Night Watch, Thief of Time,

and

Small Gods,

reminds us of Zen master Lao-tzu, writer of

Tao Te Ching,

and blind Master Po, the Shaolin monk who trained Kwai Chang Caine in the 1970s TV series

Kung Fu.

Other members of the order include Marco Sotoâthe monk who finds promising novice Lobsang Ludd; the Master of Novices; the Abbot (with his “circular aging,” a phrase meaning reincarnation); chief acolyte Rinpo; and Qu, a monk inventor/weapons master like Q in the James Bond series.

Instead of a TARDIS (the Doctor's police box/time travel machineâa sentient machine the initials of which stand for “Time and Relative Dimension(s) in Space”), a time machine à la H. G. Wells, or a souped-up DeLorean used by Dr. Emmett Brown in

Back to the Future,

the monks' mode of time travel is the portable procrastinator, which slices time. (More on them in

chapter 19

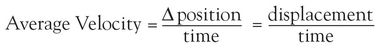

.) As they slice, the monks get to Zimmerman Valley, a time-slicing state that can't simply be calculated by a velocity formula like:

Back to the Future,

the monks' mode of time travel is the portable procrastinator, which slices time. (More on them in

chapter 19

.) As they slice, the monks get to Zimmerman Valley, a time-slicing state that can't simply be calculated by a velocity formula like:

With Zimmerman, we can't help thinking of a cross between Silicon Valley and Dean Zimmerman, a Rutgers professor who wrote a paper with the heading “Defending an âA-theory' of Time,” which we saw on the Internet. Undoubtedly a coincidence.

Perhaps it's only fitting that Wen the Eternally Surprised, founder of the Monks of History, and the personification of Time are the parents of Lobsang Ludd. It takes time to make time.

On the monastery grounds, you find the Mandala, sands showing the currents of time. This concept didn't originate with Pratchett. According to Hindu beliefs, the Mandala is a sand graph of the universe, one used for purposes of contemplation. We would prefer to contemplate a box of Thin Mints and a stretch of white sand in Jamaica. But that's just us. (For more on the Mandala, see

chapter 19

.)

chapter 19

.)

But Is It ⦠Art?

Years ago (okay, I will admit it was during the early 1980s; yes, I'm that old) during my senior year at Northwestern, I [Linda] took a drawing class taught by late Chicago artist Ed Paschke, one of the professors at NU. In between sessions involving sketching unclothed modelsâsessions I giggled throughâour class took a tour of some of the north side art galleries in Chicago. In one gallery, a young man proudly exhibited his sculpture (I'm not sure what else to call it) to his adoring public, one of whom apparently was his patroness, a tiny elderly woman in a fur coat who looked as if she dripped money.

His sculpture consisted of a paint roller standing in a paint tray. He'd set the roller on fire. Why, I don't know. For the effect, maybe? While it burned merrily, his patroness beamed. I could only gawk and wonder,

Is that ⦠art?

He seemed to think so. I wondered how much his patroness had shelled out for him to create that ⦠thing, or how much (if anything) he would charge for it. Judging by a nearby wall

filled with other pieces of ⦠art consisting of three large sticks nailed together in varying criss-cross shapes and bearing price tags in the hundreds of dollars, I would guess a great deal of money.

Is that ⦠art?

He seemed to think so. I wondered how much his patroness had shelled out for him to create that ⦠thing, or how much (if anything) he would charge for it. Judging by a nearby wall

filled with other pieces of ⦠art consisting of three large sticks nailed together in varying criss-cross shapes and bearing price tags in the hundreds of dollars, I would guess a great deal of money.

The question

But is it art?

comes up a lot in the Discworld novels. After all, numerous art pieces adorn the museum that is Discworld. Mr. Tulip, one of the thugs hired by the zombie lawyer, Mr. Slant, on behalf of Lord de Worde (for more about them, see

chapter 12

) provides a lesson in Discworld art appreciation in

The Truth.

I've taken some of his advice, and that of other art connoisseurs to heart, to explore the state of the arts in Discworld.

But is it art?

comes up a lot in the Discworld novels. After all, numerous art pieces adorn the museum that is Discworld. Mr. Tulip, one of the thugs hired by the zombie lawyer, Mr. Slant, on behalf of Lord de Worde (for more about them, see

chapter 12

) provides a lesson in Discworld art appreciation in

The Truth.

I've taken some of his advice, and that of other art connoisseurs to heart, to explore the state of the arts in Discworld.

Â

Check out the brush strokes.

I've never been to the Musée du Louvreâthe home of some of the most well-known pieces of art in the world, so I have to rely on the witness of others, not to mention a viewing of

The Da Vinci Code.

During a trip to Paris in the mid-1990s, my older brother Chris and sister-in-law Lisa stood in a really long line at the Louvre to see Leonardo's

Mona Lisa.

They told me they were impressed by the sheer age of the painting. (They didn't bring back a T-shirt, though.)

I've never been to the Musée du Louvreâthe home of some of the most well-known pieces of art in the world, so I have to rely on the witness of others, not to mention a viewing of

The Da Vinci Code.

During a trip to Paris in the mid-1990s, my older brother Chris and sister-in-law Lisa stood in a really long line at the Louvre to see Leonardo's

Mona Lisa.

They told me they were impressed by the sheer age of the painting. (They didn't bring back a T-shirt, though.)

The

Mona Ogg,

painted by Leonard of Quirm, is, of course, a parody of the

Mona Lisa,

with artist/engineer Leonard acting as the Leonardo da Vinci of Discworld. If you've seen the cover of

The Art of the Discworld,

you've seen the

Mona Ogg,

which supposedly was inspired by a young Nanny Ogg. But

Woman Holding Ferret

by Leonard of Quirm is an allusion to Leonardo's

Lady with an Ermine,

painted in 1485. (Speaking of Leonardo,

The Koom Valley Codex

mentioned in

Thud!

is an allusion to

The Da Vinci Code

.)

Mona Ogg,

painted by Leonard of Quirm, is, of course, a parody of the

Mona Lisa,

with artist/engineer Leonard acting as the Leonardo da Vinci of Discworld. If you've seen the cover of

The Art of the Discworld,

you've seen the

Mona Ogg,

which supposedly was inspired by a young Nanny Ogg. But

Woman Holding Ferret

by Leonard of Quirm is an allusion to Leonardo's

Lady with an Ermine,

painted in 1485. (Speaking of Leonardo,

The Koom Valley Codex

mentioned in

Thud!

is an allusion to

The Da Vinci Code

.)

Theme-wise,

Three Large Pink Women and One Piece of Gauze

by Caravati (an allusion to Italian Baroque artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio perhaps?) reminds me of the ballerina pictures by Impressionist painter/sculptor Edgar Degas, including

Three Ballet

Dancers, One with Dark Crimson Waist,

and

Three Dancers in Violet Tutus.

Of course, Caravaggio was known for paintings with such simple descriptive names as

Boy Bitten by a Lizard

and

Boy with a Basket of Fruit.

Charming.

Three Large Pink Women and One Piece of Gauze

by Caravati (an allusion to Italian Baroque artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio perhaps?) reminds me of the ballerina pictures by Impressionist painter/sculptor Edgar Degas, including

Three Ballet

Dancers, One with Dark Crimson Waist,

and

Three Dancers in Violet Tutus.

Of course, Caravaggio was known for paintings with such simple descriptive names as

Boy Bitten by a Lizard

and

Boy with a Basket of Fruit.

Charming.

The Battle of Ar-Gash

by Blitzt (like

blitz

) seems to be a parody of Leonardo da Vinci's

Battle of Anghiari

(1503-6).

The Battle of Koom Valley

by Methodia Rascal, a huge painting that hangs in the Royal Art Museum in Ankh-Morpork in

Thud!

, is reminiscent either of of paintings by Jan Matejko, a nineteenth-century Polish painter known for battle scenes such as the

Battle of Grunwald,

or an eighteenth-century American artist John Trumbull who, like Matejko, was known for military figures and battle scenes, including the

Battle of Trenton,

the

Battle of Princeton, The Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown,

or

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Trumbull worked during the time of the American Revolution and later.

by Blitzt (like

blitz

) seems to be a parody of Leonardo da Vinci's

Battle of Anghiari

(1503-6).

The Battle of Koom Valley

by Methodia Rascal, a huge painting that hangs in the Royal Art Museum in Ankh-Morpork in

Thud!

, is reminiscent either of of paintings by Jan Matejko, a nineteenth-century Polish painter known for battle scenes such as the

Battle of Grunwald,

or an eighteenth-century American artist John Trumbull who, like Matejko, was known for military figures and battle scenes, including the

Battle of Trenton,

the

Battle of Princeton, The Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown,

or

The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Trumbull worked during the time of the American Revolution and later.

Waggon Stuck in River

by Sir Robert Cuspidor reminds me of the

Haywain

triptych by Hieronymus Bosch in 1500-15. Whether it was actually inspired by Bosch's work is anybody's guess.

by Sir Robert Cuspidor reminds me of the

Haywain

triptych by Hieronymus Bosch in 1500-15. Whether it was actually inspired by Bosch's work is anybody's guess.

Man with Big Fig Leaf

by Mauvaise reminds me of the fig-leaf controversy surrounding works by the famed Italian Renaissance master Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (Michelangelo to his friends). Daniele Ricciarelli (a.k.a. Daniele da Volterra), a painter and sculptor, painted a fig leaf over a certain part of the male anatomy in Michelangelo's fresco

The Last Judgment

during a time when nudity in paintings was considered a no-no.

by Mauvaise reminds me of the fig-leaf controversy surrounding works by the famed Italian Renaissance master Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (Michelangelo to his friends). Daniele Ricciarelli (a.k.a. Daniele da Volterra), a painter and sculptor, painted a fig leaf over a certain part of the male anatomy in Michelangelo's fresco

The Last Judgment

during a time when nudity in paintings was considered a no-no.

Â

Watch out for fakes.

In the 1966 movie

How to Steal a Million,

starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter O'Toole, and Charles Boyer, Audrey played Nicole, the beleaguered daughter of an art forger (Charles Bonnet, played by Hugh Griffith) who paints like van Gogh and had a father who sculpted in the style of Benvenuto Celliniâthe sixteenth-century sculptor/painter known for his

Perseus

sculpture and his

Diana of Fontainebleau

bronze figure. The conflict begins when Charles sells his “Cellini”

Venus

âwhich was made by his fatherâto a museum, claiming to be an art collector. Audrey convinces O'Toole's characterâSimon Dermottâto help her break into the museum to steal it, to avoid having her father revealed as a forger.

In the 1966 movie

How to Steal a Million,

starring Audrey Hepburn, Peter O'Toole, and Charles Boyer, Audrey played Nicole, the beleaguered daughter of an art forger (Charles Bonnet, played by Hugh Griffith) who paints like van Gogh and had a father who sculpted in the style of Benvenuto Celliniâthe sixteenth-century sculptor/painter known for his

Perseus

sculpture and his

Diana of Fontainebleau

bronze figure. The conflict begins when Charles sells his “Cellini”

Venus

âwhich was made by his fatherâto a museum, claiming to be an art collector. Audrey convinces O'Toole's characterâSimon Dermottâto help her break into the museum to steal it, to avoid having her father revealed as a forger.

The Cellini of Discworld might be Scolpiniâa sculptor mentioned during Mr. Tulip's art discussion in

The Truth.

We don't actually see Scolpini's work, but we're told how to spot a real one and the fact that anyone could steal the piece Tulip views. Shades of the plot to

How to Steal a Million.

The Truth.

We don't actually see Scolpini's work, but we're told how to spot a real one and the fact that anyone could steal the piece Tulip views. Shades of the plot to

How to Steal a Million.

Remember the Chicago art gallery pieces mentioned earlierâthe twigs and the paint roller? In

Thud!

two pieces by Daniellarina Pouter brought back memories for me:

Don't Talk to Me About Mondays,

which looks like a pile of rags, and

Freedom

âa stake with a nail in it. Beauty is indeed in the eye of the beholder.

Thud!

two pieces by Daniellarina Pouter brought back memories for me:

Don't Talk to Me About Mondays,

which looks like a pile of rags, and

Freedom

âa stake with a nail in it. Beauty is indeed in the eye of the beholder.

Â

Pay attention.

Leonardo da Vinci's studies on the perception of the human eye and the effects of light changed the way that painters viewed their craft. He paid attention to the design of the human body and took into account what the eye really sees: how much color close up and at a distance; how the form/shape of the eye (with all of its parts) affects its overall function, particularly in gauging the proportions of an object. This helps a painter correctly depict limbs on people in paintings. Foreshortening happens when the artist doesn't take into account what his or her eye is really seeing.

Leonardo da Vinci's studies on the perception of the human eye and the effects of light changed the way that painters viewed their craft. He paid attention to the design of the human body and took into account what the eye really sees: how much color close up and at a distance; how the form/shape of the eye (with all of its parts) affects its overall function, particularly in gauging the proportions of an object. This helps a painter correctly depict limbs on people in paintings. Foreshortening happens when the artist doesn't take into account what his or her eye is really seeing.

We can't really see a painting like

Three Large Pink Women and One Piece of Gauze

unless an artist like Paul Kidby draws it, so it's hard to gauge whether the artist, like Leonardo da Vinci, is a student of the eye's form and function.

Thief of Time

does reveal that

The Battle of Ar-Gash

by Blitzt features a striking use of light. Perhaps Leonardo would have been pleased.

Three Large Pink Women and One Piece of Gauze

unless an artist like Paul Kidby draws it, so it's hard to gauge whether the artist, like Leonardo da Vinci, is a student of the eye's form and function.

Thief of Time

does reveal that

The Battle of Ar-Gash

by Blitzt features a striking use of light. Perhaps Leonardo would have been pleased.

Â

What's music to some is only so much noise to others.

Let's turn now to the world of musicâan art form as varied in Discworld as it is in our world. ClassicalâDoinov's Prelude in G is mentioned in

Maskerade,

and

Ãberwald Winter,

an opera the Wintersmith loves, in

Wintersmith

; popâ“music with rocks in” is described in

Soul Music

. There's ethnic musicâ“Gold, Gold, Gold,” a dwarf refrain (

Feet of Clay

); and bawdy comic songsâ“The Hedgehog Song.” And then there are the songs with a patriotic twist, such as “Carry Me Away from Old Ankh-Morpork,” “I Fear I'm Going Back to Ankh-Morpork,” and “We Can Rule You Wholesale”âthe Ankh-Morpork civic anthem. Music to stir your soul and conscience.

Let's turn now to the world of musicâan art form as varied in Discworld as it is in our world. ClassicalâDoinov's Prelude in G is mentioned in

Maskerade,

and

Ãberwald Winter,

an opera the Wintersmith loves, in

Wintersmith

; popâ“music with rocks in” is described in

Soul Music

. There's ethnic musicâ“Gold, Gold, Gold,” a dwarf refrain (

Feet of Clay

); and bawdy comic songsâ“The Hedgehog Song.” And then there are the songs with a patriotic twist, such as “Carry Me Away from Old Ankh-Morpork,” “I Fear I'm Going Back to Ankh-Morpork,” and “We Can Rule You Wholesale”âthe Ankh-Morpork civic anthem. Music to stir your soul and conscience.

Everyone in Discworld has an opinion about music. In

Soul Music,

which details the musical career of Imp y Celynâa.k.a. Buddy Holly (an obvious allusion)âthe question is whether music with rocks in is a legitimate form of expression. (According to the Guild of Musicians, the answer is no, unless they can profit by it.) Well, it is an issue that causes a lot of trouble for Discworldians. This subject has been long debated, since the early days of rock, back when the real Buddy Holly was alive, and continues even today with regard to rap.

Soul Music,

which details the musical career of Imp y Celynâa.k.a. Buddy Holly (an obvious allusion)âthe question is whether music with rocks in is a legitimate form of expression. (According to the Guild of Musicians, the answer is no, unless they can profit by it.) Well, it is an issue that causes a lot of trouble for Discworldians. This subject has been long debated, since the early days of rock, back when the real Buddy Holly was alive, and continues even today with regard to rap.

And of course, Granny has an opinion every time Nanny tries to sing “The Hedgehog Song.” (See

Witches Abroad.

) Is it art? Is “The Hokey Pokey”? It all depends on what you like.

Witches Abroad.

) Is it art? Is “The Hokey Pokey”? It all depends on what you like.

The same argument can be made for the Discworld series. Some may balk at the parodies and puns. “But is it art?” they ask. If you're reading this book, we think you know the answer to that question already.

Other books

21 Blackjack by Ben Mezrich

The Countess by Lynsay Sands

The Thief by Ruth Rendell

Savage Magic by Judy Teel

Edsel Grizzler by James Roy

Touch of Trouble (Touch Series) by Dee, Cara

Her Reaper's Arms by Charlotte Boyett-Compo

Make Believe by Ed Ifkovic

Lost Cargo by Hollister Ann Grant, Gene Thomson