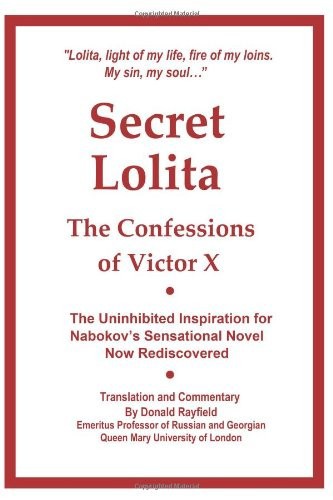

Secret Lolita: The Confessions of Victor X

Read Secret Lolita: The Confessions of Victor X Online

Authors: Donald Rayfield,Mr. Victor X

PREFACE

Confessions of Victor X

were unearthed, like an unexploded bomb, in 1980 when Nabokov's and Edmund Wilson's excited reactions to them were published.

They were originally written in French and sent to Havelock Ellis in 1912. Far too explicit, they could not be published in English then, and few readers, if any, came across them when they were printed in the French edition of Havelock Ellis's monumental studies in sexuality.

Reading them in the British Library, I was so struck by the graphic honesty and extraordinary insights that I translated them on the spot. A further year's research convinced me that they were genuine and I traced the real authorship. To honour Havelock Ellis's promise of anonymity, I shall go on calling the writer Victor X.

The confessions as an erotic document need little further comment; but they also give a glimmer of light into real Russian provincial life a century ago and they tell us a lot about Vladimir Nabokov's

Lolita

and her seducer, Humbert Humbert, who is perhaps Victor X's only posterity.

The reader, when he recovers from the confessions, can mull over these insights in my postface.

DONALD RAYFIELD.

Edited by Donald Rayfield

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

First published in 1984 by

CALIBAN BOOKS

London and Dover, New Hampshire

First Grove Press Edition 1985

First Printing 1985

ISBN: 0-394-54630-X

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 84-73544

First Evergreen Edition 1985

First Printing 1985

ISBN: 0-394-62055-0

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 84-73544

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

X, Victor.

The confessions of Victor X.

"Translation from the French edition of Havelock Ellis' Studies in the psychology of sex"—P.

1. Sex customs—Soviet Union—History. 2. X, Victor. 3. Child molesters—Italy—Biography. 4. Soviet Union—Social conditions—1801-1917. I. Rayfield, Donald, 1942- . II. Title.

HQ18.S65X2 1985 306'.092'4 84-73544

ISBN 0-394-54630-X

ISBN 0-394-62055-0 (pbk.)

Printed in the United States of America

GROVE PRESS, INC., 196 West Houston Street, New York, N.Y. 10014

1 3 5 4 2

Studies in the Psychology of Sex

.

I am greatly indebted to Professor François Lafitte (Havelock Ellis' literary executor) for his kind assistance and to the archivist of Turin's municipal library for his help.

Donald Rayfield

Chapter 2 - Enlightenment

Chapter 3 - Initiation

Chapter 4 - Debauch

Chapter 5 - Last Liaisons

Chapter 6 - Italian Respite

Chapter 7 - Final Fall

Postface by Donald Rayfield

CHAPTER 1

INNOCENCE

These are the sexual confessions of a southern Russian, born about 1870, of good family, educated and capable, like many Russians, of psychological analysis; he prepared this confession in French in 1912. These dates must be kept in mind to understand some of the political and social allusions.

Knowing from your work that you believe science can profit from a detailed biographical account of the development of various individuals' instincts, normal or otherwise, I thought I should let you have a thorough record of my own sexual life. My account may not be all that interesting from the scientific point of view (I am not competent to judge), but it will at least have the merit of being absolutely exact and truthful; moreover it will be very full. I shall try to recollect my most minute memories on that subject. I suspect that most educated people are too prudish to disclose this aspect of their biography to the world at large; I shall not follow their example and I feel that my experience in this field, so unhappily precocious, confirms and complements many of the observations I have found scattered in your work. Naturally you may do as you wish with my notes and, as is your practice, you will preserve my anonymity.

I am of Russian nationality (of mixed Great-Russian and Ukrainian origin). I know of no congenital defects in my parents or ancestors. All my grandparents were very healthy people, longlived and psychologically very well balanced. My uncles and aunts were likewise longlived and had strong constitutions. My father and mother were the offspring of prosperous country landowners. They were brought up in the country. Both of them had an absorbing intellectual life. My father was a director of a bank and chairman of an elected rural district council (a

zemstvo

) on which he led a heated struggle for forward-looking ideas. Like my mother he had very radical opinions and wrote articles on political economy and sociology in newspapers and magazines. My mother produced books of popularized science for children and for the people. My parents were very much preoccupied by their social struggles (which were of a completely different nature from today's struggles in Russia), by books and discussions, and they were, I think, a little negligent in the education and supervision of their children. Of the eight children they had, five died in infancy; two more died at seven and eight and I was the only one of the eight to reach adulthood. My parents were always in good health; death was due to external hazards. My mother was very headstrong, almost violently so; my father was highly-strung but could control himself. They probably did not have very erotic temperaments for when I reached manhood their marriage was still a model union. There was not a hint of any love story except the love that had resulted in their marriage - absolute fidelity on both sides, a fidelity that amazed the world around them, where such virtue was a rarity. (Russian "intellectuals" had a very free, even lax morality in sexual matters.) I never heard them talk about anything scabrous. The family life of other relatives, uncles and aunts, had a similar atmosphere - austere in morals, conversation, intellectual and political interests. Belying the forward-looking ideas of all my relatives, some of them had a little innocuous aristocratic vanity, though without any haughtiness: they were noble in the Russian sense of the word. (Russia's nobility is far less aristocratic than western Europe's.)

My childhood years were spent in several large towns of southern Russia, mostly in Kiev. In summer we would go to the country or the seaside. I remember that up to six or seven, although I shared a bedroom with my two sisters (one was two years, the other three years younger than me) and bathed with them, I did not even notice that their sexual organs were any different from mine. It is very true to say that we see only what interests us! (In children, so close to animals, it is particularly obvious that perception is utilitarian; admittedly, children are curious, but surely not because their curiosity is disinterested?)

Here is something relevant that I recall. At six or thereabouts (I can be sure of my age because of some associated memories) I decided one day to dress my little four-year-old sister up in my sailor suit. This took place in a bedroom where there was a chamber-pot which I started pissing in after undoing my trouser flies. Then I proffered the pot to my sister and told her to do the same. She undid her flies, but of course did not have a penis to pull out - not that I knew that - and pissed in her trousers. My sister's clumsiness outraged me and I could not understand at all why she had not pissed the same way as me, and yet this incident told me nothing about our anatomical differences. I have another 'urinary' memory from further back - I must have been about five.

At that time there was a little girl about my own age living with us. She was, I found out later, the daughter of a streetwalker who died leaving a two-month-old baby - this little girl. The death happened in a big house where we had rented one floor, and my mother took in the baby, found her a wet-nurse and decided to bring her up with her own children. Interestingly for those who believe in the heredity of morals, however, this child revealed from earliest infancy strong depraved tendencies, despite having absolutely the same upbringing as the rest of us and although she had no idea she was an adopted child. We had no idea that she was not our sister, nor did she, and our mother was just as much 'mummy' to her as to us. We were very loving, tender children, always caressing each other and we loved her as we loved each other, kissing and coaxing her, whereas the little demon never wanted to do anything but hurt us. When she got bigger, we became aware of her character. We ended by seeing that, for example, whenever there was a chance, she would do something that broke our 'baby' code, with the infallibility of a physical law. For instance, if she talked about what had happened in the nursery when the grown-ups were away, she would always tell lies about her playmates. She had a passion for inciting children to do something bad and then immediately going off to denounce the evildoer. She was very clever at sowing discord between adults (servants and so on) with slanderous inventions. We adored animals, but she would torture them - to death if she could - and would then put the blame on us when our parents came. She liked giving presents, but she did so - and this was a rule without any exception - only to take them back immediately and to relish the victim's tears. She was physically stronger and more cunning in her evil than us, so that we were her butts. If she hit us, we did not dare complain; if she slandered us, we could not prove our innocence. She kept on stealing or destroying our toys, she was very greedy and took our share of treats, whenever we children were not being watched closely.

Oddly enough, nevertheless we didn't have the slightest ill-feeling against her and went on loving her,

because she was our sister

. Doubtless that was due to children's mental debility; they sometimes love those that ill-treat them (brutal parents, for example), since they cannot reason about actions. All we knew was that brothers and sisters were supposed to love one another, and we obeyed this rule of ethics. When she was six, this little girl made up her mind to steal some money that our maid had hidden in her bed. My sisters and I also knew that the maid used to put money under her mattress, but not only were we horrified by the very idea of theft, we were not in the least interested in having money. Our companion, however, brought up under the same conditions as us, lacking nothing, naturally, and having the same toys, already had instinctive covetousness! Around the same time she apparently made sexual passes at us, but I have no memories of that episode; generally, my recollections of the first six years, of my existence are fragmentary and incomplete. My mother was alarmed by her adopted child's precocious development of vicious tendencies, was afraid of her proximity affecting us too and finally sent her away from the family: the little girl was entrusted to one of my aunts, a very charitable old maid with philanthropic ideas. This noble person grew extremely fond of our foster-sister and brought her up as best she could - but all in vain: Olga was to refuse ever to work at grammar school and at eighteen she abandoned her benefactor and was already plying her mother's trade. At twenty-two she was sent to Siberia for theft and attempted murder. I have made this rather long digression, for I was struck by Wundt's opinion: in his

Ethik

he claims that Spencer's teachings that moral tendencies can be inherited are pure fiction. I think Olga's story would appear to show that hereditary moral tendencies (in this case education played no part) show up early in some children. But I return to my story.

I recall then that I was playing in the garden with three other children, when I suddenly thought (why? I don't know, but I am certain that sexual feelings were not a reason) I should piss in an empty matchbox (at that time in Russia matchboxes were cylindrical like little goblets) and give my sisters urine to drink. The three little girls meekly obeyed and dutifully swallowed the contents of the goblet which I refilled when empty. Little Olga found this weird pastime particular fun, but since telling tales was her dominant characteristic, she could not wait to run to the house and tell our mother everything. That child's inclination for sneaking was beyond explanation, for our parents always tried to give us the deepest loathing of denunciation, constantly telling us that there was nothing worse than being an

informer

and always scolding Olga when she tried to 'tell'. But tale-bearing and slander were irresistible passions for her. She hated everybody and tried to hurt them, though she was given nothing but affection and love. The psychology may seem unlikely, but it is a fact. Once again I think it can only be sadly accounted for by heredity. When Olga was sent away from our house, my mother devised some fantastic story to explain what had happened. But at long intervals we still saw Olga, who lived from then on with my aunt in the country. We knew about the little girl's thieving, because we witnessed it, but we had not thought it to be particularly important. Even less were we struck by her handling our sexual organs, since I had quite forgotten the incident and was told about it only much later. When Olga was ten, my aunt moved to our town to send Olga to grammar school as a day-girl, and I was able to see my former companion more often: it was only then that I learnt that she was not really my sister.