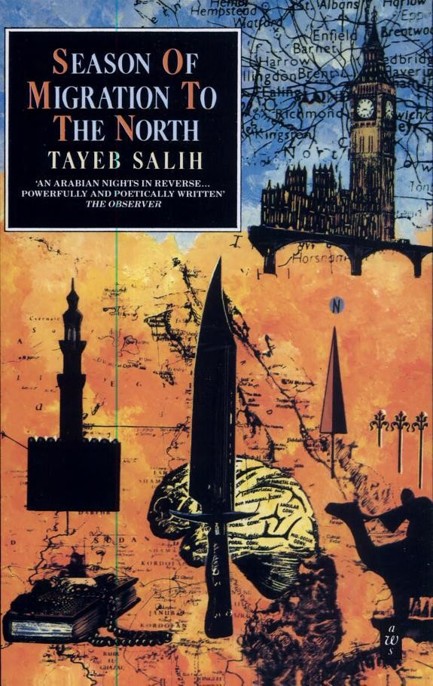

Season of Migration to the North

Read Season of Migration to the North Online

Authors: Tayeb Salih,

TAYEB

SALIH was born in 1929 in the Northern Province of Sudan, and has spent most of

his life outside the land of his birth. He studied at Khartoum University

before going to England to work at the British Broadcasting Corporation as Head

of Drama in the Arabic Service. He later worked as Director-General of

Information in Qatar in the Arabian Gulf; with UNESCO in Paris and as UNESCO’s

representative in Qatar. Culturally, as well as geographically, Tayeb Salih

lives astride Europe and the Arab world. In addition to being well read in

European literature, his reading embraces the wide range to be found in

classical and modern Arabic literature as well as the rich tradition of Islam

and Sufism. Before writing

Season of Migration to the North

, Tayeb Salih

published the novella

The Wedding of Zein

, which was made into an Arabic

film that won an award at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976. He has also written

several short stories, some of which are among the best to be found in modern

Arabic literature, and the novel

Bandarshah

.

DENYS

JOHNSON-DAVIES is the leading translator of Arabic fiction into English. Born

in Canada, he studied Arabic at the Universities of London and Cambridge. He

has to date published some twenty volumes of novels, short stories, plays and

poetry from modern Arabic literature. He is a Visiting Professor at the American

University in Cairo.

WAIL

S. HASSAN teaches in the Department of Comparative and World Literature at the University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of

Tayeb Salih: Ideology

and the Craft of Fiction (2003)

and of numerous articles on Arabic and

comparative literature. A native of Egypt, he has lived in the United States

since 1990.

TAYEB

SALIH

SEASON

OF MIGRATION TO THE NORTH

TRANSLATED

BY DENYS JOHNSON-DAVIES

INTRODUCTION

BY WAIL S. HASSAN

INTRODUCTION

The

back cover of the first Heinemann edition of this novel, published in English

translation in 1969, featured the following statement by Edward W Said, one of

the most influential literary and cultural critics of the second half of the

twentieth century:

‘

Season

of Migration to the North

is among the six finest novels to be written in

modern Arabic literature.’ Almost two decades earlier, another critic, Albert Guerard,

wrote in his introduction to the 1950 New American Library edition of Joseph

Conrad’s

Heart of Darkness

that it was ‘among the half-dozen greatest

short novels in the English language’. In praising Salih’s novel, Said was

quoting almost verbatim Guerard’s famous appraisal of Conrad’s classic. Said

was himself an expert on Conrad, having published a book on him in 1966, so

what he wrote about Salih’s novel was calculated to equate its importance to

that of Conrad’s within their respective literary traditions: just as

Heart

of Darkness

is a masterpieces of English literature, so is

Season of

Migration to the North

an equally great classic of modern Arabic

literature.

Later on, in his major book

Culture and Imperialism

(1993),

Said argued that Salih’s novel reverses the trajectory of

Heart of Darkness

and

in effect rewrites it from an Arab African perspective. If Conrad’s story of

European colonialism in Africa describes the protagonist’s voyage south to the

Congo, and along the way projects Europeans’ fears, desires, and moral dilemmas

upon what they called the ‘Dark Continent’, Salih’s novel depicts the journey

north from Sudan, another place in Africa, to the colonial metropolis of

London, and voices the colonised’s fascination with, and anger at, the coloniser.

Both voyages involve the violent conquest of one place by the natives of

another: Kurtz is the unscrupulous white man who exploits Africa in the name of

the civilising mission, while Mustafa Sa’eed is the opportunist black man who

destroys European women in the name of the freedom fight. Both novels also

depict a ‘secret sharer’ or a double — Marlow in Conrad’s tale and the unnamed

narrator in Salih’s — who are at once obsessed and repulsed by Kurtz and

Mustafa Sa’eed, respectively.

This way of reading novels from former European colonies as

counter-narratives to colonial texts is one of the strategies of postcolonial

literary criticism. Postcolonial critics have argued that narratives of

conquest by writers such as Daniel Defoe, Rudyard Kipling, Ryder Haggard, Joseph

Conrad, E.M. Forster, Joyce Cary and others are crucial to understanding

British culture. Even the seemingly insular and domestic world of Jane Austen’s

Mansfield

Park

depends for its sustenance,

according to Said, on the existence of the British Empire in general, and on

slave labour in Antigua in particular. Postcolonial critics also emphasise

those literary texts from formerly colonised countries that portray the ravages

of imperialism and directly challenge the authority and the claims of colonial

discourse. In some instances, postcolonial writers have done so by rewriting

canonical texts of conquest. In

A Tempest

, for example, Aimé Césaire

rewrote Shakespeare’s

The Tempest

from the perspective of Caliban; J.M. Coetzee’s

Foe

is an alternative version to Defoe’s

Robinson Crusoe

; and

several writers, including Chinua Achebe, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, V.S. Naipaul and Tayeb

Salih have responded in various ways to Conrad’s novels, especially

Heart of

Darkness

, which has emerged as the single most important, controversial and

influential narrative of empire, in addition to being a key text of British

modernist fiction. Of the novels that rewrite

Heart of Darkness

,

Season

of Migration to the North

is the most structurally and thematically

complex, and the most haunting.

If postcolonial criticism, a phenomenon that emerged in

American and British universities in the 1980s, has enhanced the reputation of Salih’s

novel in its English translation, the Arabic original,

Mawsim al-hijira ila

al-shamal

, became an instant classic as soon as it was published in Beirut

in 1966. Although this was not Salih’s first novel, he was still relatively

unknown at the time. The impact of the novel on the Arab literary field was

such that in 1976, a group of leading critics compiled a collection of essays

in which they hailed Salih as

abqari al-riwayya al-rabiyya

(genius of

the Arabic novel). The novel appealed to its Arab readers, first of all,

because of its aesthetic qualities — its complex structure, skilful narration,

unforgettable cast of characters, and its spellbinding style which evokes the

wide range of intense emotions displayed by the characters as it moves

gracefully from lyricism to bawdy humor to searing naturalism and the uncanny

horror of nightmares, and from the rhythms of everyday Sudanese speech

(captured in literary Arabic rather than in the Sudanese dialect as in some of Salih’s

other works) to poetic condensation, and from popular song to classical poetry

and the lofty idiom of the Qur’an. Indeed, Salih remains one of the best Arabic

stylists today, a quality inevitably lost to non-Arabic speakers, although Denys

Johnson-Davies’s English translation is outstanding.

The second reason for which the novel created such a stir on

the Arabic literary scene in the mid-sixties was the radical way in which it

responded to Arab liberal discourse on Europe. That discourse began with a

movement called the

Nahda

(revival or renaissance) that sought, from the

mid-nineteenth century onwards, to rebuild Arab civilisation after centuries of

decay under the Ottoman Empire and to confront the threat of European

imperialism. The

Nahda

attempted to weld together two elements: Arab

Islamic heritage on the one hand, and modern European civilisation, especially

its scientific and technological achievements, on the other. Far from

conceiving the two as contradictory or incompatible, the second seemed to

Nahda

intellectuals to be the natural extension of the first, in view of the

great advances in scientific and humanistic knowledge that medieval Arab civilisation

had produced, and which contributed in no small measure to the European

renaissance of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Therefore, the project of

the

Nahda

consisted in selectively synthesising the material advances of

modern Europe and the spiritual and moral world view of Islam.

However, this conciliatory vision became more difficult to

sustain as Europe began to colonise parts of the Arab world in the late

nineteenth century and especially after the First World War. Arabs had joined

forces with the Allies against the Ottomans in exchange for the promise of

independence, a promise that was broken after the war. Moreover, the Balfour

Declaration of 1917 promising the establishment of a jewish national home on

Arab land and European support for the State of Israel deepened Arab

resentment. Thus by the 1950s, the secular ideology of pan-Arab nationalism

became dominant, and the

Nahda’

s vision of cultural synthesis gave way

to an antagonistic stance toward the West. The collapse of that ideology in the

1967 war with Israel spelled a profound identity crisis that resonated at all

levels of Arab consciousness and called for new ways of conceptualising the

past, present, and future, even while it further solidified essentialised

notions of Self and Other, East and West. Not surprisingly it was during the

following decade that the militant ideology of Islamic fundamentalism emerged

to fill the void.

Begun in 1962 and published in 1966, the novel diagnosed the

Arab predicament during that turbulent decade by stressing the violence of the

colonial past, of which Mustafa Sa’eed is a product; announcing the demise of

the liberal project of the

Nahda

, championed by Western-educated

intellectuals like the narrator who failed to account for imperialism in their vision

of cultural synthesis; condemning the corruption of postcolonial governments;

and declaring the bankruptcy of traditionalist conservatism hostile to reform,

represented by the village elders. The final scene of the novel, and especially

its last words, forecasts the state of existential loss and ideological

confusion that many in the Arab world would feel in the wake of the 1967 war.

Tayeb Salih was born in 1929 in the village of Debba in

northern Sudan. He attended schools in Debba, Port Sudan, and Umm Durman,

before going to Khartoum University to study biology. He then taught at an

intermediate school in Rafa’a and a teacher training college in Bakht al-Rida.

In 1953, he went to London to work in the Arabic section of the BBC, and during

the 1970s he worked in Qatar’s Ministry of Information, then at UNESCO in Paris.

Since then, he has lived in London.

Salih’s enormous reputation rests on relatively few works of

fiction. In addition to

Season of Migration to the North

, he has written

a novella,

‘Urs al-Zayn

(1962, in English

The Wedding of Zein

),

another novel,

Bandarshah

(first published in Arabic in two parts,

Dau

al-Beit

in 1971 and

Meryoud

in 1976), and nine short stories, two of

which appear in the Heinemann edition of

The Wedding of Zein and Other

Stories

(1969). In 1988, he began writing a column in the London-based

Arabic weekly magazine

Al-Majallah

; those articles on literary cultural

and political topics were collected under the title of

Mukhtarat

(Selections)

and published in nine volumes in Beirut in 2004-05.

As a Sudanese, Salih came from a liminal place where the Arab

world merges with black Africa, and he wrote as an immigrant in London. His

fictional village of Wad Hamid in northern Sudan represents the complexities of

that location: situated between the fertile Nile valley and the desert,

inhabited by peasants but a frequent stop for nomadic tribes, it is a meeting

place for several cultures. Its religion, ‘popu1ar Islam’, is a mixture of

orthodox Islamic, Sufi, and animist beliefs. The village is beset by tensions

that have defined Arab modernity since the nineteenth century: between old and

new, science and faith, tradition and innovation. Because he was an immigrant, Salih

could write about the colonial metropolis from a vantage point inaccessible to

Levantine Arab intellectuals of his and earlier generations, even those among

them who had studied in Europe for a while then returned home, often dazzled.

He also felt the predicament of the native there more intensely than they did,

both as an African and as an Arab. Such a unique perspective ensured that his

enormous talent would produce the most powerful representation of colonial

relations yet in Arabic literature.