Season in Strathglass (2 page)

Read Season in Strathglass Online

Authors: John; Fowler

Snug's the word for the little house that Stuart built.

|

Louise, a dreamer who smiles at adversity, with Fritz (on the left). Horses are her passion.

Boris the wild boar and progeny at the trough. All gone to market now.

Shinty match at Cannich. Strathglass under attack.

Sister Petra Clare, âhermit iconographer', adds a last detail to her virgin and child.

INTRODUCTION

Fifteen years or so ago, I walked across the Highlands with Catherine, now my wife. We went from the Beauly Firth in the east to the west coast and stopped for the night at a remote hostel beyond Loch Affric. I made supper but, before the spaghetti was on the table, Catherine, new to walking, had fallen fast asleep, her head on the table.

Pinned to the noticeboard in the kitchen was a brief history of the area, including this:

Affric was one of a group of glens which were traditional routes from west to east.

Twelve shepherds and two gamekeepers and their families lived in West Affric in the 1850s. When cheap imports of refrigerated mutton made shepherding uneconomic and high rents could be charged from sporting tenants, West Affric became part of the massive deer forest of a Canadian railway magnate called Winans . . .

No one lives in West Affric nowadays except for hostel wardens who come and go. As for Winans the railway magnate (not Canadian but American), there will be more to tell.

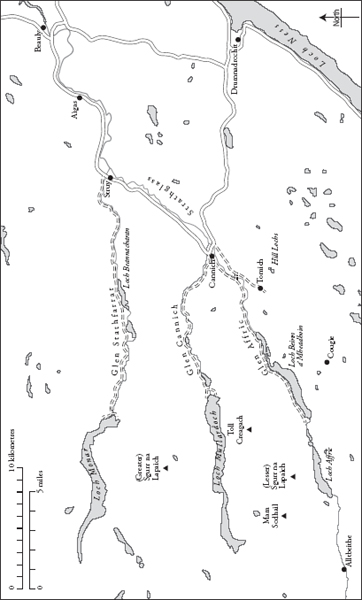

My old guidebook to the mountains of the western Highlands declares that âStrathfarrar, Cannich and Affric are three of the longest glens in Scotland and are universally regarded as her three most beautiful'. There have been dramatic changes since the words were written but even now, in spite of widespread flooding for hydroelectricity and blanket conifer afforestation, they still ring true today.

Down these three glens pour three rivers which merge at length as the

River Glass, whose dark waters flow for several miles through a flat valley or strath, hence the name Strathglass. For a while, over a decade, I made many visits to the three glens and the strath of Glass, always lured back by the grandeur of the scenery and the character of the people who live there. As a kind of shorthand, I came to style the whole area in my mind simply as âAffric', a name that has a particular resonance for me. It was the first of the glens I got to know, a place of craggy hills, ancient pinewoods and many waters, almost too theatrical to be true. And so, when I used to say, on leaving home, âI'm going to Affric,' my wife and friends knew what I meant and where I'd be. Sometimes Catherine came with me.

Mostly I came by way of Beauly. Beauly,

beau lieu

â âbonny place' â and so it is. It's a small country town set in a pastoral landscape half an hour's drive from Inverness. It has a modest sense of style and a pleasant air of gentility. Here the River Glass, which started life as the Affric deep in the hills of the west, briefly becomes the River Beauly in the last stage of its long life. The hills are left behind and the sea is close. Another approach is from Drumnadrochit, a ragged village on Loch Ness where tourists decant in hope of sighting the monster. The shop tills there ring an anthem to Nessie.

This narrative is based on diaries I kept during my time in Affric and Strathglass. Because the period covers several years, the result is kaleidoscopic or impressionistic and I've not attempted to keep to a strict chronology. But I think it holds together.

It's some time since my last spell in Affric and there have been changes since. You'll find some in the postscript.

Strathglass and glens Affric, Cannich and Strathfarrar

1

There's an email from Tim.

It's been very wet in the glen over the past few weeks and now serious flooding. My cattle got trapped on a very small island and I had to swim out to them with a bale of hay and lead them swimming back to dry land â very cold! If winters continue in this vein I'm not sure how habitable parts of the highlands will be in 10 to 15 years' time.

All the same, I go.

There are flood warnings all the way north and water sluices over the road. Past Struy, where the River Glass swings close to the road, a sheet of water has swamped road, fields and riverbank, barring the way. I'm reluctant to drive through â how deep is it?

An approaching Land Rover and trailer churn slowly through the water, throwing up bow waves. The burly driver, a farmer by the look of him, comes over as I sit watching from the car. âYou'll get through,' he says. âKeep to the crown of the road. Canny as you go.'

Cannily I go.

The well-known surroundings are transformed. Strathglass is a different country, the riverbanks broken and submerged and the strath inundated here and there. Trees stick up from pools like tropical rainforest, islets speckle lagoons where there was only dry land before and newly formed burns pouring down from the high ground swill across the road.

My temporary home for the next few nights is a caravan in Cannich village. Rain drums on the van roof overnight and, in the morning, it's raining still, though with lessened force. I was cold in bed â three degrees. No newspapers in the shop â they didn't get through â and no post. The overside road is closed and the news is that the road down to Drumnadrochit is flooded just before the village. The Beauly road could be blocked if it gets worse. There might be no way out. Marooned!

Tim takes me to meet Sheena, who farms cattle in the glen, and we stand at the gate in our wellies, in a welter of mud. Tim admits he didn't actually swim, though it was touch and go. He waded out breast high towards his stranded animals holding a heavy bale of hay above his head while two of his daughters stood at the water's edge in case of emergency. After a good deal of cajoling, wheedling, calling the cattle by their names (he named them after the girls at the forestry office, though the girls don't know that yet), the hungry heifers edged off dry land into the water and followed him back to safety. Keeping his feet was a problem and several times he was in danger of lift-off.

Tim asks Sheena if she's noticed an increase in flooding since she's farmed here. She reflects a little â no, the waters haven't risen higher over the last 15 years or so, but probably floods have been more frequent.

Tim says that, between November and December, it rained for 46 days. That's biblical. Forty days and forty nights and then Noah pushed out the ark. It hasn't come to that yet.

âI'm going on a castration course,' Sheena remarks casually, âso that I know which bits to cut off.'

Oh. It makes you wince.

In the afternoon, I venture into Glen Cannich, where there are signs that the floodwaters are receding. The hills have disgorged themselves by now. A high tidemark of litter, branches, torn-up bracken and grass shows the extent of the flooding. Everything's still sopping wet. Big spreads of water fill the low ground and the swirling river brims under the causeway to Craskie â I shan't risk a crossing.

There's a dank mistiness in the air, a ghostly calm now that the wind has died and the rain almost stopped. Brightness comes and goes in this new world. Now and again the low sun edges through, gilds the snow-streaked hilltops and freshens all the colours of the earth â the birch groves, leafless and wine-dark, golden larch, conifer woodlands vivid green, swags of withered bracken brick-red on the hillsides. Old twisted birch stems coated with grey-green lichens dip their feet in unaccustomed pools. Then rain-mist closes the shutters again.