Sea of Ink (6 page)

Authors: Richard Weihe

Tags: #German, #Biographical, #China, #Historical, #Fiction

Fish and rocks

31

Bada Shanren had become a master and young painters came from far and wide to show him their work and seek advice. They generally brought small gifts, ink tablets from their province or jars of jam, and he would thank them politely. These visits punctuated long periods of silence, when he would immerse himself completely in his work.

Bada looked patiently at the mountains and rivers, the pines, the bamboo, all the cranes and wild geese and fish. Everything seemed so superficial, so stiff and lifeless. A heap of bones and ashes. He would then give the painter the following advice: ‘When you walk, do not think about walking, but let your feet dance on the soft forest floor. When you paint, do not think about painting, but let your wrist dance.’

Soon afterwards monks from the Monastery of the Green Cloud also visited him in his fisherman’s hut.

Once he was sitting with a monk on the shore,

speaking

of the joys of being a fish.

‘But Master, you’re not a fish,’ the monk countered. ‘How can you know whether fish can be happy?’

‘You are not me,’ Bada replied. ‘How can you know that I do not know when a fish is happy?’

‘No, I’m not you,’ the monk said. ‘So I cannot know what’s in your mind. But you are definitely not a fish. That is certain. So I doubt that you can know fish feel pleasure.’

‘Let us start at the beginning once more,’ Bada said. ‘When you asked me how I could know what fish feel, you already knew that I know, and you asked me how. My answer to this is: I know, for the happiness I feel is not my own.’

32

Shao Changheng, man of letters and

functionary

, also harboured a strong desire to meet Bada Shanren. He had studied and admired the master’s calligraphy, without ever being able to acquire any of his work.

When in 1688 Shao stayed as a guest of an abbot friend of his in the Orchid of the South Monastery near Nanchang, a well-informed monk was sent to the master’s abode to request whether Shao might be able see him. The messenger returned the following day to say that the master agreed to meet Shao Changheng in the Orchid Temple.

When the appointed day arrived it was pouring with rain. With such bad weather Shao could not expect the ageing master to keep their engagement. In spite of his doubts, however, he called for a bamboo litter and set off.

He was only halfway to the temple when Bada came running to meet Shao, gave him a warm greeting and then burst out into loud laughter. Shao saw an old man of slight build with a faintly reddish face, sunken cheeks and a thin moustache whose ends hung down in fine strands. The man was wearing a fisherman’s hat from which the rainwater dripped all around as if from a fountain. His shoes and cape were sopping wet, but this seemed not to trouble the man; he danced and sang alongside the litter on the final stretch to the monastery.

They spent half the night in conversation by

lamplight

. The master became less and less talkative, whereas his gestures became increasingly animated until his whole body moved with them.

All of a sudden Bada demanded some ink and a brush, which the monks gave him without delay. Now he started frenetically covering sheets of paper with

calligraphy

, writing dark words which Shao was unable to interpret. Bada went on in this frenzy until he collapsed from exhaustion and fell asleep on the spot.

Outside a violent storm was raging and water was swooshing from the gutters. Gusts of wind rattled the windows and doors, and around the pavilion the bamboo groaned like tigers in the deserted mountains.

There was such commotion that night that Shao could not sleep. He was overcome by an interminable sorrow, like black water flowing into an empty lake basin. He would have liked to wake the master and shed tears with him, but such things were beyond him, and he merely felt sadder as a result.

He was unable to sleep because he felt more awake than in the daytime, more awake than he had ever felt.

As the storm continued to rage, Bada remained motionless, like a drowned man.

Shao became worried and bent over him.

Bada was fast asleep, with a cheerful expression on his face.

33

Later, in summer, another young painter visited the master, asking many questions and seeking advice.

‘How can I develop my own style?’ the painter wanted to know.

‘Originality!’ Bada laughed. ‘I am as I am, I paint as I paint. I have no method, I do not think about

originality

, I am just me.’

‘But surely I have to choose the style of the Northern or Southern School.’

‘You come from no school and you go to no school. The school does not come to you, either, and no school goes forth from you. Take a brush and some ink and simply paint your own style.’

Bada could see the young man’s questioning look. So he elucidated further: ‘We do not know which style the ancients followed before developing their own painting style. And when it had reached maturity they did not allow their successors to renounce this style. For

centuries

their successors were unable to lift their heads from the ground. Like those who follow in the footprints of the ancients rather than following their own hearts. A truly lamentable state of affairs, it means a young painter becomes the slave of another, well-known painter. Apart from that, avoid flatness, excess detail and, most of all, continuing with a well-worn pattern. What is

painting

if not the technique of the universe’s changes and developments?’

‘Does that mean I don’t have to begin with the role models and attain their level of expertise before striking my own path?’ the pupil asked. ‘When you talk like that you are forgetting that besides the old role models you also have your own: yourself. You cannot hang on to the beards of the ancients. You must try to be your own life and not the death of another. For this reason the best painting method is the method of no method. Even if the brush, the ink, the drawing are all wrong, what constitutes your “I” still survives. You must not let the brush control you; you must control the brush yourself.’

34

Bada Shanren had been invited by the abbot to the Orchid Temple. They drank their fill of liquor and laughed into the summer night.

The following day Bada took leave of his host very early and set off on his way back to the fisherman’s hut where he still lived.

A fine rain had set in. Bada wandered through the pine forest beneath the monastery and breathed in the fragrance, for the damp trees were letting off an aroma. Amidst the silence he told himself, ‘You must know when the world acquired you and when the time has come to leave it. My life is fading away like the magnificence of the cherry blossom in the rain, and I feel only sadness at the emptiness which remains. I have filled it with my signs, but have I thereby proved my existence?’

He stopped. ‘Is this a suicidal thought? Or is it quite the opposite? Why does the rain have this effect on me? Surely there is nothing softer in the world than water. And surely nothing better for softening hard and severe things.’

He was approaching his dwelling. He saw the hut by the lake, squatting at the foot of the mountain, and he stopped again to savour the view.

The trees, the rocks, the mountain stream in the rain.

Everything seemed blurred and other-worldly.

Everything

playing out incessantly before him – was it merely the flow of things? Was it the trees dripping in the mist which made the world appear like that, or was it the tears in his eyes?

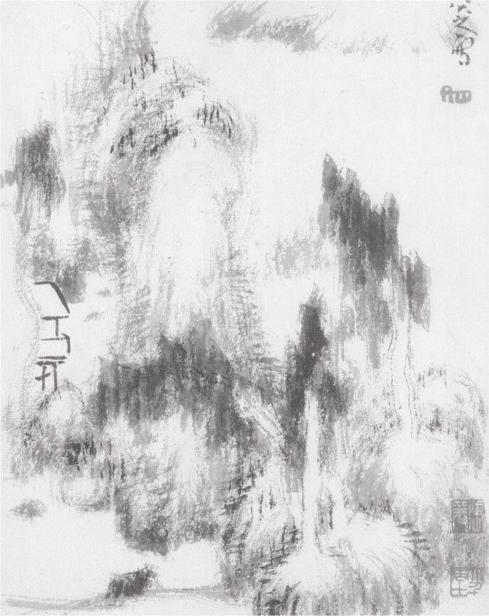

No sooner was he back in his abode than he took a large piece of paper and wiped it with the wet sleeve of his robe. He hurriedly poured water into the rubbing stone and prepared the ink.

Beginning halfway down, his gleaming black brush drew five parallel lines at variable intervals from the

left-hand

edge of the paper, an area which was barely damp. He then added seven vertical and diagonal strokes until the outline of his hut was recognizable, though half of it was cut off by the paper’s margin.

He took the brush with the cropped bristles. He turned it several times in the ink and guided it down the length of the still-moist paper, now using just the side, now pressing it down like a scrubbing brush, twisting it slightly before lifting the brush at the bottom of the paper. He thus painted a succession of column-like light and dark grey shapes which blended fluidly into one another as the damp paper dissolved the contours.

His tiny house, however, stood clearly and solidly on the mountainside, its back turned to the lamenting world and the desolate mountain behind a curtain of rain.

Fine streams of ink ran down the mountain; indeed the entire mountain seemed to flow away as if it were nothing more than a large wound of the world.

He wrote his name on the picture and added the date:

Painted on the night of the 27th day of the ninth month

. He did not put the year. His pictures did not exist in the calendar of the new dynasty.

Landscape with hut

35

Some years had passed since that September night. Bada Shanren had reached the age of seventy. He addressed a letter to a friend in which he described his daily routine:

I have a clean table beneath a light window. I read the ideas of dead masters from a past dynasty. I close the book and light an incense stick while contemplating what I have read. When I feel I have understood something I am happy and I smile to myself. With a brush and some ink I

express

my thoughts and empty my mind. An important guest arrives, but we put formalities aside. I make some green tea and together we enjoy the wonderful poems he has brought with him. After a while, deep yellow rays from the evening sun illuminate the room, and in the door frame I can see the rising moon. The visitor leaves and crosses the stream which flows into the lake by my house. Then I close the door and lie down on my mat. Lying on my back, I watch the moon through the window. I remain lying there, motionless, feeling carefree and content. I listen to the sound of a solitary cricket. Who is outside composing an elegy for me? My thoughts are carried far away.

36

It was spring. Bada Shanren was sitting on a narrow veranda, thinking of his wife. Where might she be now?

Despite the sun it was raining heavily.

The embankment was a pale green.

A pair of herons flew past, brushing the weeping willow.

A swim, then joyful leaps in the naked light.

The curtain of rain lifted, the view extended as far as the jade horizon, along lathe-turned balustrades of cloud without end.

The water in the lake mirrored the fading sky, the trees held the fog like censers, gradually allowing the eye to make out their forms once more.

Bada was absorbed by the distant view to the south.

This tiny heart, he thought, and eyes which gaze into the infinite.

And he could hardly tell whether he was painting this picture in his mind or whether he was really looking at it.

He waited and observed every change. The clouds looked so dense, it seemed as if he could carve great blocks out of them.

He imagined a house in the sky built from blocks of cloud.

37

As the years passed, life in isolation became too arduous. Bada Shanren decided to return to his home city of Nanchang.

He rented a shabby room in Xifumen, a poor area in the southern part of the city.

Tall plants covered the façade, coiling around doors and windows and darkening the room.

Bada liked these plants; he wanted to live beside them and so moved in, even though the houses were desolate and run-down.

The room was in a wretched condition: the window frames were rotten and everything was thick with dust.

But he had immersed himself so deeply into the spirit of Chan that his external surroundings were practically immaterial.

The dust and lack of light could not impair his brushes.