Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 (45 page)

Read Science Fiction: The 101 Best Novels 1985-2010 Online

Authors: Damien Broderick,Paul di Filippo

The year 1897 in Copenhagen finds our young heroine-narrator, Charlotte Schleswig, struggling to make a living as a whore. Burdened by the care of a gluttonous and slatternly mother—Charlotte insists that Fru Schleswig, the slovenly pig, cannot possibly be related to a beautiful princess such as herself—our working girl is always on the alert for a more lucrative scam. She believes she’s landed on easy street when she and her mother get a housecleaning job with Fru Krak, a rich and egotistical widow. While the elder Schleswig labors away sweeping up dust bunnies, Charlotte pilfers whatever’s not nailed down to pawn.

Fru Krak’s husband, it turns out, mysteriously vanished seven years ago. His disappearance is connected with a locked room in the basement of the Krak manor. Charlotte’s curiosity is aroused, and she breaks in one night with her mother. They discover a curious contraption, and before you can say “Terry Gilliam’s

Time Bandits

,” they are accidentally transported to our era’s London. There they find Professor Krak, hale and hearty, living among a surreptitious refugee community of fellow time-traveling Danes.

Charlotte is transfixed by the modern age, especially when she falls in love with a dashing young Scottish archaeologist, Fergus McCrombie. Soon she induces Professor Krak to sponsor a Christmas visit back to 1897, to introduce Fergus to her native era. Once back in “history,” everything goes wrong. Charlotte is separated from both Fergus and the Professor, and only her own ingenuity can restore the lovers.

Jensen has immense fun with this setup. Her depiction of period Copenhagen is rich and sensorially deep. (Nor is this choice of nationality for Charlotte merely arbitrary. Jensen invokes, both overtly and covertly, the spirit of Hans Christian Andersen and his famous fairytales as a template for Charlotte’s life story.) Of course we also get the expected but still humorously contrived reactions of a visitor from the past to modern life, as well as some neat chrono-paradox mindblowers. The characters are all humanly endearing, with every high-minded, principled stand undercut by carnality or vice-ridden selfishness. And yet the whole narrative is full of warm good-heartedness. All of these virtues are couched in Jensen’s vibrant prose that goes down easy, yet is full of nuggets of observation and wit. “The Pastor…was a paunchy man in his middle to late years, with clattering false teeth that seemed to roam his mouth like a tribe of nomads in search of land on which to pitch camp.”

Discovering the work of Liz Jensen is like stumbling on a time-machine in a basement: you have no idea of where it will take you, but you know it’ll be a hell of a ride.

84

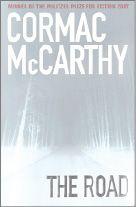

Cormac McCarthy

Road

(2006)

LIKE ALL FICTION

and much art, sf displays figures acting (or stymied) in a landscape. As noted in earlier entries, for most literary fiction its figures and landscape are familiar to the intended reader, and their portrayal is nuanced, shaded, closely examined to a degree possible only with the already well-known. By contrast, so-called genre fiction usually has different goals and means: characters are often gaudy, overlit, driven by wild passions, moving through extravagant landscapes sketched with comic strip boldness and exaggeration.

Sf is especially remarkable for its emphasis on inventive settings, landscapes none of us has trodden outside dream or imagination. One extreme is the landscape of final desolation, of apocalypse and post-apocalypse—the world blighted by global nuclear war or genocidal plague, or literally destroyed, the Sun gone nova, whole galaxies obliterated in immense spectacle. In Greg Bear’s

The Forge of God

(1987), chunks of neutronium and antineutronium are fired into the Earth’s core by aliens; the mutual annihilation tears the planet apart. Charles Pellegrino and George Zebrowski’s

The Killing Star

(1995) wrecks Earth with targeted relativistic bombs striking at 0.92 of light speed, and finally the Sun itself is destroyed as a few survivors flee into deep space.

Cormac McCarthy

’s

Pulitzer-winning novel

The Road

is not rationalized in this fashion, and the post-catastrophe landscape through which his unnamed man and boy trudge, pushing their shopping cart from frigid mountains to fouled sea, is never explained. Most life other than human is dead: no trees, crops, grass, birds, fish. The sky is gray and cold, rain and snow and drifting ash blight the world, which rumbles with immense distant upheavals. Ten years earlier, the nameless man and his pregnant wife experienced the end of their world: “The clocks stopped at 1:17. A long shear of light and then a series of low concussions. He got up and went to the window… the power was already gone. A dull rose glow in the windowglass.”

A reader schooled in the protocols of science fiction, with its attention to background as well as the figures roaming its roads, immediately asks: what happened? How did this occur? Where’s the radiation poisoning? Many conventional readers, captivated by Oprah’s TV championing of the novel, take the

mise

-

en

-

scène

to be a harsh warning of environment despoliation, the ruined world a victim of unchecked climate change. Others suppose that this is the nuclear winter dreaded for decades. Neither explanation makes sense. McCarthy’s calamity could be due to relativistic bombardment (but there is no sign of malign aliens, who would make this a very different kind of story), or the kind of asteroid impact or series of super-volcano eruptions that destroyed the dinosaurs.

Arguably these are absurdly inappropriate concerns, like probing the economic system of Samuel Beckett’s

Waiting for Godot.

If so, can we fruitfully read

The Road

as sf, or is this at best misguided and at worst an act of grasping subcultural appropriation? No less a commentator than Michael Chabon denies that the novel is science fiction, while noting that “the post-apocalyptic mode has long attracted writers not generally considered part of the science fiction tradition. It’s one of the few subgenres of science fiction, along with stories of the near future (also friendly to satirists), that may be safely attempted by a mainstream writer without incurring too much damage to his or her credentials for seriousness.”

Many readers, then, take

The Road

as an allegory, a stripped-down fable, a sort of harrowing of hell, a liturgy for a terminal world that requires no detailed explanation and would be damaged by one. It is simply a schematic future we dread, a cannibal distillation of everything vile in human nature, a sort of naturalistic

Inferno

for the 21st century. The narrative voice seems to support such a reading. Dialogue has no opening or closing quotes, reducing speech to part of the flat surface of the eviscerated planet. Punctuation is spare or absent, so that “can’t” becomes (confusingly) “cant,” and “won’t” becomes “wont”; one wit called

The Road

a post-apostrophic novel.

But this is a habitual quirk of Cormac McCarthy, a 1981 MacArthur Genius fellow, not new-minted for a world stripped even of conventional grammar. And while much of the narrative is undecorated to a degree Hemingway or Raymond Carver might have envied, it lifts now and then into high-toned passages closer to James Joyce at his most biblical. The very ending of the novel is a paean to the lost landscape of our full living world, and the boy is told that “the breath of God was his breath yet though it pass from man to man through all of time.” Will there be time, though, beyond this awful lifeless desolation, drained of the divine essence (mystic Jakob Boehme’s

salitter

: “The salitter drying from the earth”)? There are hints that the man is an apostate theologian, a scholar despairing of books, while the boy (who nurtures within him “the fire”) is a sort of Paraclete of the end times. Will the hum of mystery return in the deep glens where brook trout once stood in the amber current? It seems a forlorn hope.

The Road

runs between two narrative worlds: the canonized territory of literature and the suspect landscapes of paraliterary genre, horror, science fiction. We readers push our shopping carts along this rutted, contested path, diving for protection to one side or the other as the bookless barbarians surge by. Read

The Road

as sf, accepting its corrosive world without fussing at its engine, and the spare or heightened voices can sweep you into a new kind of slipstream fiction that blends old and new.

85

Naomi Novik

(2006)

[Temeraire sequence]

IN 2007

, Naomi Novik won the John W. Campbell award for best new sf or fantasy writer, awarded for her gloriously entertaining novel

His Majesty’s Dragon

(the original title

Temeraire

was used

in the UK). A blend of the late Patrick O’Brian’s Captain Aubrey/surgeon Maturin Napoleonic naval wars series and perhaps Anne McCaffrey’s Pern dragons, it presented an alternative turn-of-the-nineteenth century differing from our world in the presence of large, intelligent, domesticable flying dragons. What’s especially significant in this warm series are the superbly wrought, lovingly observed dragons, and their jealous bond with favored humans.

His Majesty’s Dragon

was only the first of a saga now intended to run to nine volumes. The first three, originally published at monthly intervals to maintain momentum, are the Temeraire trilogy; the next three, the Laurence trilogy. The sixth book,

Tongues of Serpents,

set largely in 19th century penal Australia, came out in 2010, with

Crucible of Gold

scheduled for 2012. Although the overall sequence was thus incomplete in 2010, extending beyond our time frame, this grand and compelling series comprises one large work of delightful allohistorical imagination that clearly deserves to be listed among the best sf (not fantasy) books of the last quarter century. It swiftly developed a devoted following, and already has a wiki dedicated to its characters, background, divergences from true history, and

detailed timeline

.

[1]

Captain Will Laurence commands the

HMS Reliant

in 1805 when he meets and bests the French frigate

Amitié

in the growing conflict with Napoleon. Taken as a prize of war, this vessel proves to hold a rare treasure—the egg of a Chinese Imperial. Newly-hatched dragons bond with whichever human harnesses them, but only if they choose to. Baby Temeraire has grown attached to Laurence even in the egg (during which time dragons learn the languages they hear, and emerge fully articulate, opinionated, feisty as adolescents, and tremendously hungry). Laurence is dismayed by this attachment, since he is now obliged to leave a promising career in the navy for the despised ranks of the Royal Aerial Corps. In snobbish and class-prejudiced England, the raffish airmen (and, shockingly, airwomen) have little prospect of marriage—their dragons are furiously jealous creatures—let alone station or wealth. The pair are dispatched to Loch Laggan, in Scotland, a bleak training grounds. For Will Laurence’s father, Lord Allendale, this is a bitter blow, and his fiancé dumps Will to hastily wed another aristocrat with better prospects.

From this uncomfortable, even disagreeable beginning, Laurence swiftly develops a fondness for his brilliant draconic charge and companion. Novik’s presentation of the dragons is delicious:

“I can hear that you are unhappy,” Temeraire said anxiously. “Is it not good that we are going to begin training? Or are you missing your ship?... If we do not care for it, surely we can just go away again?” […]

“It is not so easy; we are not at liberty, you know,” Laurence said. “I am a King’s officer, and you are a King’s dragon; we cannot do as we please.”

“I have never met the King; I am not his property, like a sheep,” Temeraire said. “If I belong to anyone, it is you, and you to me. I am not going to stay in Scotland if you are unhappy there.”

“Oh dear,” Laurence said; this was not the first time Temeraire had shown a distressing tendency to independent thought….

Their relationship is full of fertile ambiguities. Laurence is in a sense the dragon’s father-figure, but Temeraire is never really a child, and isn’t much like a human, either, despite his clear and articulate speech. While the former naval officer is driven by military and aristocratic virtues, especially honor (after one contretemps he even gives himself up to authorities at the risk of summary execution, rather than decamp dishonorably), the young dragon is an anarchist from the moment he leaves his shell. Most of all, they are boon comrades. As he grows in size and power, Temeraire becomes in turn a sort of affectionate father or larger brother to Laurence, tucking him under his great wing as shelter from ill weather: