Scent and Subversion (3 page)

Read Scent and Subversion Online

Authors: Barbara Herman

In our celebrity-obsessed, perfection-seeking, conventionally aspirational society, perfume invites us to embrace alternative values: the louche, the queer, and the decadent. Subversive perfumes in an already subversive medium posit an indie aesthetic that values art over commerce, niche over blockbuster, and individualism over conformity.

Smell is our underground sense and links us to sex, emotion, memory, and those messy things our allegedly logical culture tries to repress. In other words, scent is subversive, and

Scent and Subversion

is both a record and a reflection of my journey through twentieth-century perfume.

I view perfume as an aesthetic object of pop culture that is worthy of analysis, shaped by and shaping the culture in which it is embedded. Perfume is a language whose speech is worth learning and unpacking as one would a poem, book, or film. Scent is a path to getting closer to our senses, to instinct, and to our bodies and the earth at a time when those attachments are threatened. As I write this, Google Glasses are promising—or threatening, depending on your position on the ever-increasing encroachment of technology into our lives—to “bring information closer to your senses” by mediating our experience in the most extreme way to date, filling our sight lines with virtual information. As if we need to be even more divorced from our senses!

In

Part I

of

Scent and Subversion

, I discuss the path that led me to perfume and the exciting rise in scent-centric culture, including the online communities that continue to facilitate it.

Part II

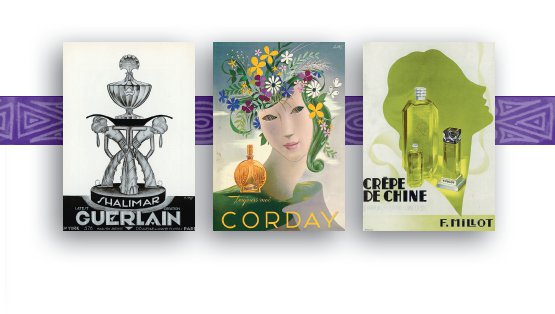

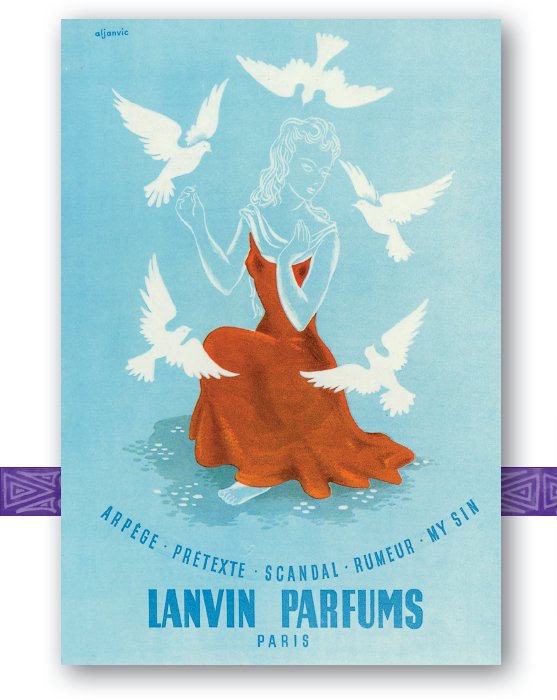

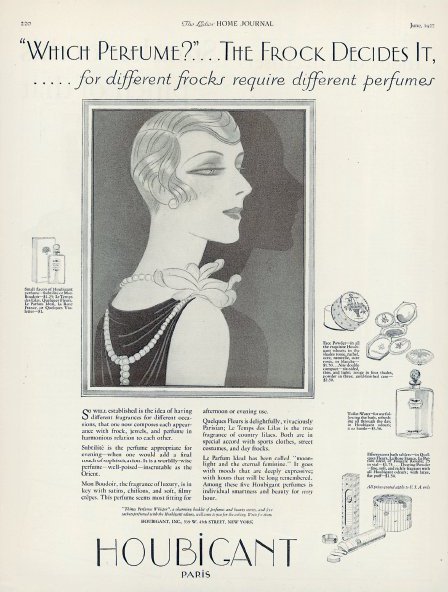

includes descriptions and histories of more than three hundred vintage perfumes, decade by decade, from Jicky to Demeter’s Laundromat (2000), covering drugstore as well as haute perfumes. (A perfume can be considered vintage if it’s been discontinued, if its style is no longer “in,” or if it’s at least twenty years old.) Over the years, I’ve collected more than a hundred vintage perfume ads. Some of my favorites are sprinkled throughout the text, like movie posters to perfume’s invisible cinema.

Part III

looks to the future through conversations with perfumers and scent provocateurs who are thinking about perfume in a profound way, some who are even rethinking its importance and purpose in society. Part III’s “A Brief History of Animal Notes in Perfume” explains the aesthetic, historical, and cultural importance of animal-derived ingredients that are no longer used in nonsynthetic form in perfumes, even as it acknowledges both the theoretical and real problems with sourcing animal notes from actual animals.

Finally, a Perfume Glossary helps elucidate terms used in this book, and will arm you with a vocabulary to begin your journey through scent.

I hope that

Scent and Subversion

inspires you to explore both vintage and contemporary perfume, to pay attention to the smells that surround us, and to see perfume as instructive, a bridge between the world and our oft-neglected sense of smell. Like reading poetry to understand the lyricism possible in demotic, everyday speech, smelling perfume connects us to the olfactory wonderland that is around us.

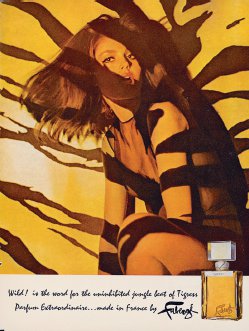

This 1938 perfume gets the ’60s treatment.

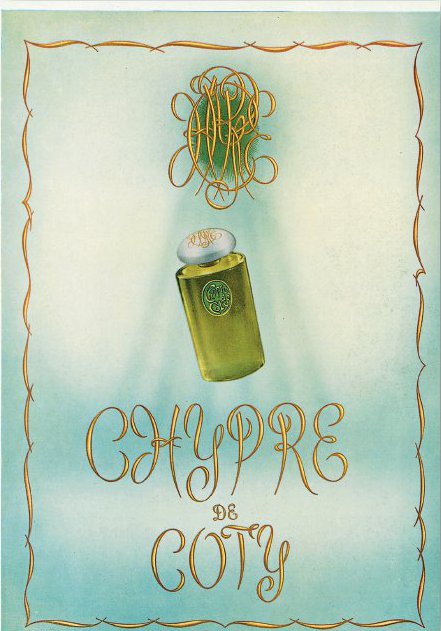

The perfume that started its own category, François Coty’s 1917 Perfume Chypre (Cyprus in French) was named as an homage to the scents that perfumed that Greek island, which included citrus, floral, and moss notes.

Fougère Royale, Jicky, Chypre (1882–1919)

A

s single-note floral perfumes began to wane in popularity, perfumes with complex floral bouquets such as Houbigant’s Quelques Fleurs (1912) rose to prominence. With its overdose of raunchy civet, Guerlain’s Jicky (1889) retained the nineteenth century’s love of animalic notes, while bringing in a sense of abstraction to perfumery through a novel use of new synthetic ingredients. It combined notes and accords that, in their sum, smelled like nothing in the world. Even Fougère Royale (Royal Fern), with its beguiling name, didn’t smell like ferns but rather like bergamot, lavender, and coumarin, which at the time was a new and synthetic molecule found in abundance in tonka beans. Fougère, with that trio of notes, remains a perfume category today.

Unless otherwise specified, the perfume notes listed below each entry have come from various editions of Haarmann & Reimer’s

The Fragrance Guide: Feminine and Masculine Notes—Fragrances on the International Market

. In some cases, H&R’s notes are supplemented with additional sources.

by Houbigant (1882)

Perfumer:

Paul Parquet

With a wonderful balance between sunny, herbaceous top notes and a spicy, warm and rich base, Fougère Royale smells like the cleanest, freshest facets of summertime—a waft of lavender here, some notes of hay and moss there, rounded out by vanilla, tonka, and spice from carnation and florals. Vintage Fougère Royale smells more subtle and natural than its reissued version.

Named after a plant with no smell, Fougère Royale (“Royal Fern”) spawned a whole perfume category: the fresh-aromatic, lavender-accented fragrance accords with oakmoss and woody notes that are still referred to as

fougère.

Fougère Royale was the first fragrance to use synthetic coumarin, one of the main components in tonka beans with a rich sweetness that rounds off other perfume notes.

Top notes:

Lavender, clary sage, spikenard, bergamot, petit grain

Heart notes:

Geranium, rose, heliotrope, carnation, orchid

Base notes:

Oakmoss, musk, tonka, hay, vanilla

by Guerlain (1889)

Perfumer:

Aimé Guerlain

Unless you are blessed with an adventurous nose, Jicky is not a love-at-first-sniff scent. Between the blast of citrus, lavender, and herbs, followed by the glorious stink of Guerlain’s famous overdose of civet, this icon of modern perfumery is the olfactory equivalent of difficult listening music. But if you acquire a nose for it, particularly the vintage, it will pay you back in spades. A rich animal warmth rises up to meet the herbaceous citrus/lavender opening, warming down to a vanillic smoothness. By turns frisky and indolent, Jicky has the personality of a cat.

Considering Jicky’s longevity—it is considered the oldest continuously produced perfume since the advent of modern perfumery—you realize that sometimes with perfume, more is more.

Top notes:

Lemon, mandarin, bergamot, rosewood

Heart notes:

Orris, jasmine, patchouli, rose, vetiver

Base notes:

Leather, amber, civet, tonka, incense, benzoin

by Grossmith (1891)

Soft, musky, animalic, woody, and balsamic, with a medicinal and herbal edge, this review of Phul-Nana, or “lovely flower,” is for the twilight phase of this over one-hundred-year-old perfume that was originally inspired by Indian flowers. Touted as a “rare marriage of the herb garden with the flower garden,” its rich woods and spice base is prominent to my nose because its top notes have dissipated.

Notes not available.

by Lubin (1900)

Upon first application, Lubin’s Cuir de Russie (Russian Leather) smells like Tabu and Youth Dew mixed with Secret of Venus, rubbed on an old leather club chair—sweet, spicy, dark, and ambery. The unmistakable leather scent, curiously, arrives at the beginning with a pronounced ylang-ylang/jasmine floral bouquet and a spicy balsamic base. An hour into the drydown, this century-plus perfume settles its creaky bones down, and I can get a glimmer of what it might have been once everything settles into place: a velvety dose of dark leather.

Notes not available

.

by Santa Maria Novella (1901)

As far back as the sixteenth century, Peau d’Espagne (“Spanish Leather” or “Spanish Skin”) was a scent made of floral and spice essences designed to mask the stinky smell of animal hides, which were traditionally cured with animal urine, pigeon and dog feces, and animal brains. It evolved into scented leather sachets, cooking spices, and women’s perfume. A search of Perfume Intelligence (an amazing online perfume encyclopedia) shows us that in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, there were already over forty brands of Peau d’Espagne, including a Roger & Gallet and L.T. Piver.

If you want to experience a naturalistic leather, look no further than Santa Maria Novella’s Peau d’Espagne, one of the few to survive into the twenty-first century. Even though this is not a review of the vintage version, (one of just a few in this book), the currently available formula is about as close to a true living vintage as any perfume around. It is challenging, difficult, gorgeous, and captivating all at once—definitely one of the strongest leather perfumes I’ve encountered. Herbaceous, anisic, meaty-smoky, and then incongruously sweet and ambery. This stuff is so strong you can almost taste it.

In

Studies in the Psychology of Sex,

twentieth-century sexologist Havelock Ellis claimed that Peau d’Espagne was “often the favorite scent of sensuous persons,” in part because of its use of “the crude animal sexual odors of musk and civet.” Mysteriously, he also believed it was one of the only perfumes that “most nearly approaches the odor of a woman’s skin.”

Notes from SMN’s website:

Linaloe (Linaloe berry has some similarity to bergamot, mint, and lavender), birch, saddle leather

by Coty (1905)

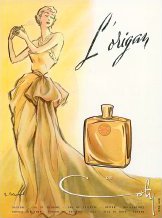

A circa 1950 advertisement for Coty’s L’Origan

Perfumer:

François Coty

Although L’Origan by Coty was said to have influenced Guerlain’s L’Heure Bleue, it seems less melancholy and more sensual/gourmand, like a licorice-flavored biscotti with floral, clove, and amber notes. Rich, ambery, and powdery, L’Origan’s gentle softness is aided by the addition of methyl ionone, a synthetic note discovered in 1893 that smells like the powdery, orris aspect of violet.

Top notes:

Bergamot, mandarin, coriander, pepper, peach

Heart notes:

Clove, clove bud, ylang-ylang, orchid, rose, orris, jasmine

Base notes:

Sandalwood, cedarwood, labdanum, musk, benzoin, vanilla

by Guerlain (1906)

Perfumer:

Jacques Guerlain

A century before Christopher Brosius of CB I Hate Perfume evoked nature with his perfumes Soaked Earth and Violet Empire, Jacques Guerlain sought to express in perfume form the scent and mood of nature after a rainstorm. In Après L’Ondée (“After the Rainshower”), the scent of earth, woods, roots, leaves, and flower petals washed by rain and warmed by sunlight radiate from its diaphanous violet/orris heart. Spicy,

woodsy, and lightly sweet, Après L’Ondée’s simplicity is in the service-restrained expression rather than minimalism for its own sake, the scent of fragrant things behind a veil of water.

Notes:

Violet, anise, orris, carnation, vanilla

by Caron (1911)

Perfumer:

Ernest Daltroff

Black Narcissus … the name suggests nighttime, malignancy, eroticism. Famously dubbed the “film noir perfume” for expressing in perfume language that genre’s contrast between light and dark, white flowers and animalic musk, Narcisse Noir, like a femme fatale, gives the impression of being both beautiful and dangerous. Just as thick, honeyed florals rise up, the darker animalic base provides the necessary edge—the “noir” of the perfume.

In

Black Narcissus

(1947), Michael Powell’s hypnotically beautiful film, nuns relocate to a convent in the Himalayas only to become haunted by the earthly delights of their pasts. The film’s namesake Narcisse Noir signifies an enticement to the world of sensuality that contributes to one of the convent dwellers’ undoing. Its outré personality led Chanel No. 5 creator Ernest Beaux to describe Narcisse Noir in one of his notebooks as

un parfum d’une vulgarité tapageuse

—a perfume of the most striking vulgarity.

Top notes:

Narcissus, orange blossom

Heart notes:

Rose, jasmine

Base notes:

Sandalwood, vetiver, civet, musk

by Coty (1911)

Moody and dark, Styx combines L’Origan’s creamy gentleness with an incensey, spiced base. Its brooding quality befits a perfume named for the river that snakes between Heaven and Earth.

Notes from

Octavian Coifan:

Orris, vanilla, carnation

by Guerlain (1912)

Perfumer:

Jacques Guerlain

Jacques Guerlain is said to have been influenced by the blues used by Impressionist painters when creating the melancholy L’Heure Bleue (“The Blue Hour”). L’Heure

Bleue refers to the twilight hour between late afternoon and evening, when it is neither totally day- or nighttime. This liminal hour brings out extremes in flowers: “the blue hour” is when they smell their sweetest. Composed two years before the outbreak of World War I, L’Heure Bleue also evokes a prewar, romantic Paris, before darkness descended upon the city.

Sweet, spicy, and soft, with a warm base hinting of leather, L’Heure Bleue suspends a host of intense and suggestive scents in an uneasy but beautiful balance, just as the blue hour of the perfume’s name holds together, in a melancholy moment, the waning of day’s hopes and the beginning of night’s uncertainty. The almost confectionary sweetness of the perfume is balanced by the spice and sharpness of bergamot, clary sage, an herbal tarragon, and a prominent clove note.

Top notes:

Bergamot oil, clary sage oil, coriander, lemon, neroli, tarragon

Heart notes:

Clove bud oil, jasmine, orchid, rose, ylang-ylang

Base notes:

Benzoin, cedar, musk, sandal, vanilla, vetiver

by Houbigant (1912)

Perfumer:

Robert Bienamé

A bouquet in a bottle, Quelques Fleurs modernized the nineteenth-century soliflore by combining so many floral notes into a bouquet that it is difficult to pick out the individual flowers. Not quite abstraction, but complexity and artistry. Citrus oils and leafy-green notes accent this bouquet, civet adds a touch of eroticism, and woods and vanilla and sandalwood add warmth and texture. Quelques Fleurs is a complex, fresh floral whose synthetic-smelling reformulation ironically smells more dated. (Because of its novel use of aldehydes, this is the perfume that Ernest Beaux studied before composing the multiple versions of perfumes that culminated in Chanel No. 5.)

Top notes:

Citrus oils, orange blossom, leafy green

Heart notes:

Rose, jasmine, lilac, ylang-ylang, carnation, violet, orris

Base notes:

Sandalwood, musk, civet, honey, heliotrope, vanilla

Houbigant lays out the case for matching perfume to “frock” in this 1927 ad. I’m also intrigued by the “Things Perfumes Whisper” booklet of perfumes, beauty secrets, and Houbigant-perfumed sachets that you could get just for writing to them.