Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women (29 page)

Read Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mahon

Tags: #General, #History, #Women, #Social Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women's Studies

BOOK: Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women

5.44Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

When she did embark on a relationship with him, she hated sharing him with Rose Beuret, his mistress of over twenty years. They had a son, Auguste, although Rodin refused to legally acknowledge paternity. Rose grudgingly turned a blind eye to Rodin’s affairs, as long as it didn’t interfere with her role as primary mistress. Barely literate, Rose couldn’t compete with a woman like Camille on an intellectual or artistic level. Still she was devoted to him, and Rodin felt a certain loyalty to her; she had been with him since the beginning, sharing the poverty and the worry, modeling for him, and taking care of the little details, leaving him free to work.

Camille and Rodin had a private contract drawn up between them, in regard to their relationship, which wasn’t discovered until 1987 among Rodin’s papers. In the contract Rodin promised to arrange for her to be photographed in her best dress by the celebrated photographer Carjat and to take her to Italy for six months if he won the Grand Prix de Salon. She also wanted him to refuse to take on other female students. In exchange, she agreed to receive him four times a month at her studio. But the most important promise was of “a permanent relationship or liaison, to the effect that Mademoiselle Camille shall be my wife.” None of these promises were kept.

When her family discovered the truth about her relationship with Rodin, she was forced to move out into an apartment of her own. Her relationship with her mother and sister had always been difficult, and now they refused to see her. Her brother, Paul, hated Rodin for seducing his sister. Since Rodin paid the annual rent on her apartment, she was now officially a “kept” woman. Rodin found a new atelier near her apartment on the boulevard d’Italie that had a romantic and mysterious past. George Sand and her lover playwright Alfred de Musset were said to have used it for their trysts. Rodin and Camille worked side by side every day, but at the end of each day Rodin returned to the home that he shared with Rose. During the summer, they holidayed together, secretly staying at the Château d’Islette, in the Loire Valley.

For Rodin, their relationship was one of the great joys of his life. Her face and body haunted his work. He modeled several of the damned souls in

The Gates

of Hell on her. For Camille, it was more complicated. In one of the few letters that remain between the two of them, she writes a racy little love note: “I go to bed naked to make myself believe you’re here, completely naked, but when I wake it’s no longer the same.” But the postscript states: “Above all, don’t deceive me again with other women.” Models in Paris were like groupies for rock stars: ready, willing, and able. And there were stories of ugly confrontations between Rose and Camille as if the two women were dogs fighting over a particularly meaty bone.

The Gates

of Hell on her. For Camille, it was more complicated. In one of the few letters that remain between the two of them, she writes a racy little love note: “I go to bed naked to make myself believe you’re here, completely naked, but when I wake it’s no longer the same.” But the postscript states: “Above all, don’t deceive me again with other women.” Models in Paris were like groupies for rock stars: ready, willing, and able. And there were stories of ugly confrontations between Rose and Camille as if the two women were dogs fighting over a particularly meaty bone.

Camille’s fears regarding her work proved well founded. Rodin used his influence with journalists and art critics to promote Camille’s career but it wasn’t translating into commissions. And when she exhibited her work, critics focused on Rodin’s influence on her work, and not enough on her own originality. Those critics who did support her work tempered their praise with comments about how amazing it was that she, a mere woman, could create works of art. The novelist and art critic Octave Mirbeau described her as “a revolt against nature: a woman genius.”

Although her early work showed Rodin’s influence, her pieces were also daring and shocking, particularly in

The Waltz

(1893), a piece that depicts two barely clothed lovers in a sensual embrace. It was a work of such stunning eroticism that critics considered it improper. “The couple seems to want to lie down and finish the dance by making love,” Jules Renard wrote in his diary. While other female artists, such as Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, were stuck painting pictures of domestic scenes, mothers and children, Camille created sexually daring sculptures that flew in the face of propriety. The only way that Camille could get a state commission for the piece was to compromise and alter her work, clothing the lovers.

The Waltz

(1893), a piece that depicts two barely clothed lovers in a sensual embrace. It was a work of such stunning eroticism that critics considered it improper. “The couple seems to want to lie down and finish the dance by making love,” Jules Renard wrote in his diary. While other female artists, such as Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, were stuck painting pictures of domestic scenes, mothers and children, Camille created sexually daring sculptures that flew in the face of propriety. The only way that Camille could get a state commission for the piece was to compromise and alter her work, clothing the lovers.

In 1892, after an abortion, Camille ended both her professional and her personal relationship with Rodin. It was clear that he was never going to leave Rose. She was also tired of being treated as just Rodin’s student, as if she had no identity of her own as an artist. Rodin had hoped that they could stay friends but Camille made it clear that she didn’t want to see or talk to him. With him out of the picture, her relationship with her family improved, especially with her brother.

Eventually, after two years, a tentative friendship between Camille and Rodin sprang up. Despite the break, Rodin still intervened on her behalf with influential people whenever he could. In 1895, he asked the scholar Schiel Mourney to “do something for this genius of a woman (no exaggeration) whom I love so much.” He even paid for her assistant when Camille was short of money. The next ten years were the most prolific in her career, as she worked relentlessly. She was determined to make a name for herself and to find her own voice. “You can see that it isn’t Rodin’s anymore, not in any way at all,” she wrote to her brother about one piece. While her earlier work had been made up of large pieces, now she deliberately worked on a smaller scale. She was on her way to creating a new genre of narrative sculpture with pieces like

The Gossips

, which anticipated pop art. She began to use materials that were difficult to carve, such as onyx.

The Gossips

, which anticipated pop art. She began to use materials that were difficult to carve, such as onyx.

However, she became increasingly isolated. And since she was no longer working out of Rodin’s atelier, she began to run out of money. Her decision to become something of a recluse, as well as increasing ill health, made taking on pupils or working in another artist’s atelier out of the question. Suspicious and distrustful of women, Camille didn’t socialize with other female artists.

The Age

of

Maturity

is a powerful depiction of her break with Rodin. The sculpture consists of three figures: an old hag leading a middle-aged man off as a young woman is seen imploring him. When Rodin saw the sculpture, he was upset that she would make his private life so public. He used his influence to have a commission for a bronze of the statue canceled. The tenuous threads of friendship were now broken and Rodin stopped supporting her work.

of

Maturity

is a powerful depiction of her break with Rodin. The sculpture consists of three figures: an old hag leading a middle-aged man off as a young woman is seen imploring him. When Rodin saw the sculpture, he was upset that she would make his private life so public. He used his influence to have a commission for a bronze of the statue canceled. The tenuous threads of friendship were now broken and Rodin stopped supporting her work.

From that moment on, Camille became convinced that Rodin was out to get her. She began to feel that Rodin had fed on her genius like a leech, that all her vital energies had been sapped. In 1905, she had her first retrospective of thirteen pieces at a gallery but it was not well received. She soon began a slow descent into full-blown paranoia. Destroying many of her statues, she disappeared for long periods of time. She directed all her disappointment and anger at Rodin, accusing him of stealing her ideas and of leading a conspiracy to kill her, along with the Protestants, Jews, and Freemasons.

Moving to the Île St.-Louis, she lived alone in a ground-floor flat, surrounded by cats. Desperate for affection, Camille began inviting homeless people to parties whenever she had money; for these she would dress in extravagant outfits and serve champagne. Convinced that Rodin was trying to poison her, she began scrounging in garbage cans for food. After a visit to her studio, her brother, Paul, wrote in his journal: “In Paris, Camille mad. Wallpaper ripped in long strips, the only armchair broken and torn, horrible filth. Camille huge, with a dirty face, speaking ceaselessly in a monotonous and metallic voice.”

Her father tried to help her and supported her financially. But when he died in 1913, no one in her family bothered to tell her. With his death Camille lost her only protector in the family. One week later, on the initiative of her brother, she was admitted to the psychiatric hospital of Ville-Évrard. Although the form read that she had been “voluntarily” committed, Camille was forcibly removed from her ground-floor apartment through a window. She later wrote of “the disagreeable surprise of seeing two tough wardens enter my studio, fully armed and helmeted, booted, menacing. A sad surprise for an artist, instead of being rewarded, this is what I got!” Rodin was shaken by the news of her committal; he tried to visit her but was refused admittance. The Claudels had requested that Camille be sequestered completely after her cousin had brought her plight to the newspapers causing a scandal. She was allowed no communication, correspondence, or visitors apart from her immediate family. Rodin wrote to their mutual friend Mathias Morhardt offering to help by sending her money.

Over the years, as her condition improved, her doctors regularly proposed that Camille be released, but her mother adamantly refused each time, blaming Camille for bringing scandal into their lives. She wouldn’t even countenance a move to an institution near Paris, even when Camille suggested that it would save money. As the years passed, Camille gave up hope of ever being released and became resigned to her incarceration. She died in 1943, after having lived thirty years in the asylum without a single visit from her mother. No one from the family and only a few members from the hospital staff attended the funeral. Her body was never claimed by her family, although her brother, Paul, paid ten thousand francs for Mass to be said for her. After Paul’s death, his son Pierre inquired about removing her body to the family plot, but was told that her remains were buried in a communal grave.

Only ninety statues, sketches, and drawings survive to give any evidence of Camille’s talent. In 1951, Paul organized an exhibition at the Rodin Museum, which was not successful, and she slid into obscurity. That all changed in 1984, when a major exhibition of her work was again shown at the Rodin Museum in Paris, which continues to display her sculptures. It was the first step toward reclaiming her from the dustbin. But it was the 1988 film

Camille Claudel

, starring Isabelle Adjani as Camille and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin, that brought her story to a wider audience.

Camille Claudel

, starring Isabelle Adjani as Camille and Gérard Depardieu as Rodin, that brought her story to a wider audience.

It is easy to see why filmmakers were attracted to her story. A beautiful, talented artist falls for one of the greatest sculptors of the nineteenth century and becomes consumed by him to the detriment of her own career, finally succumbing to madness and ending her days in a mental institution. But her story is more complex than that. It is the story of the struggle of women artists in the nineteenth century, trying to overcome the limitations imposed on them by the conservative male establishment.

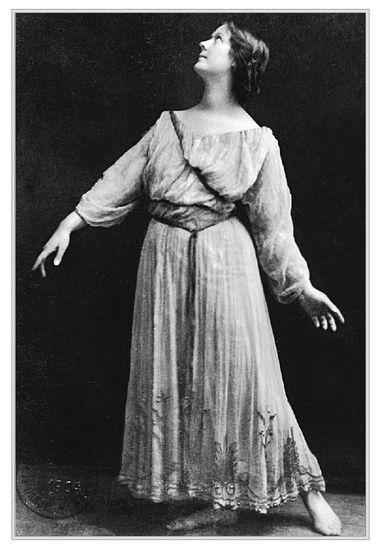

I am an expressionist of beauty. I use my body as my medium just as a writer uses words.

—ISADORA DUNCAN

Isadora Duncan claimed that she was born to dance. “If people ask me when I began to dance, I reply, ‘In my mother’s womb, probably as a result of oysters and champagne.’” Isadora’s dancing, her spellbinding influence over audiences, her lovers, and her revolutionary politics made her one of the most notorious artists of her era. Rodin sketched her, Eleanora Duse was her friend, and Stanislavsky went into raptures over her. Audiences were bowled over by her in London, Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Moscow, and Athens. Only her native country was immune to her charms and talent.

Isadora danced to classical music before it became the norm in ballet. Eschewing the usual elaborate sets, Isadora danced before simple dark blue curtains, setting a new fashion. Her costumes were as daring as her dancing. Abandoning corsets and stockings, Isadora wore a brief tunic, scandalizing audiences with glimpses of her bare arms and legs. Her dances were never set in stone, the choreography changing as her response to the music changed over the years.

A typical Gemini, Isadora’s life emphasized her dual nature. She lived out of a suitcase, but never lost her taste for luxury. From the lovely auburn-haired sylph of her youth, in middle age she became a fat, lazy hedonist who spent less and less time onstage. Isadora was a woman who dared to live and love. Her lovers were varied: millionaires, actors, musicians, designers, and countless nameless others. “Isadora could no more live without human love than she could do without food or music,” her close friend Mary Desti wrote. “They were as necessary to her as the breath of life.”

Other books

Intercepted by Love: Part 2 (Playing the Field #2) by Rachelle Ayala

Revelations: Book One of the Lalassu by Lewis, Jennifer Carole

Dude Ranch by Bonnie Bryant

The Pregnancy Plan by Brenda Harlen

Lovers and Liars by Josephine Cox

Sass & Serendipity by Jennifer Ziegler

A Warrior Wedding by Teresa Gabelman

Bayou Corruption by Robin Caroll

Front Page Affair by Radha Vatsal

The Little Sisters of Eluria by Stephen King