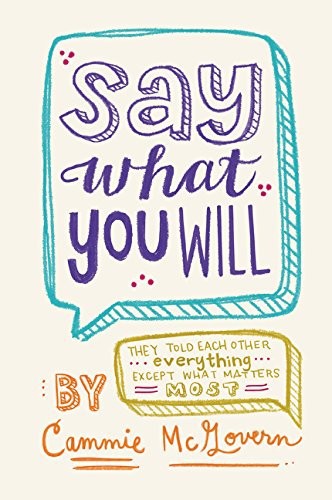

Say What You Will

Authors: Cammie McGovern

For my mom and dad.

In your fifty-four years of marriage,

you are perfect examples of my belief

that the greatest love stories

start with being best friends. . . .

Unsent message found on Amy’s computer in the hospital

You want the whole story, but you don’t realize—it’s impossible to tell the whole story. You probably think it was all about sex, but that’s where you’re wrong. It was about love. And you. Mostly you. Other people would look at me and think sex was impossible but love was not. Then it turns out, both are possible and also impossible.

A

MY’S EMAILS STARTED IN

late July and kept coming all summer. Each one made Matthew a little more nervous:

I just slipped into my mother’s office to look at the names of my new peer helpers, and I’m so happy! Your name is on the list! I thought maybe I’d scared you by coming right out and asking you to apply. I realize it’s an unusual setup, but try not to think of it as my parents offering to pay people to be my friend. I know there’s something unsettling and prideless in that. I prefer to think of it this way: my parents are paying people to

pretend

to be my friend. This will be much closer to the truth, I suspect, and I have no problem with this. I’m guessing that a lot of people in high school are only pretending to be friends, right? It’ll be a start, I figure.

The note made him anxious, but still he wrote her back:

I don’t mind, Amy. It’s a good job, plus your mother says we might get community service credit. Best, Matthew

Community service credit? For a

paid

job? I’m trying not to take this personally, Matthew, but does the job sound so onerous you should get

both money and volunteer credit

for doing it?

Sorry, you’re right. No, I didn’t mean that. The truth is I’m very glad to do this job. I don’t have a lot of friends at school, so I’m happy I’ll get to know you and the other people working with you. Matthew

PS Maybe I shouldn’t have said that thing about community service but, come to think of it, maybe your mother shouldn’t have suggested it, either. I think we all got a little confused.

Already Matthew had a feeling this wasn’t going to work out. The more he thought about it, the more certain he was it wouldn’t. He’d known Amy since second grade, but he didn’t

know

her. They weren’t friends. He remembered her, sure, but he remembered a lot of people from elementary school that he wasn’t friends with now.

Why don’t you have many friends? You seem pretty normal, right? I remember you having friends in elementary school.

I have some friends, I guess. I was never all that good when it started to be about sleepovers. Those things made me nervous.

He wasn’t sure why he’d written that. Being too honest was always a mistake—especially with someone like Amy, he was afraid. He had no idea what he’d say if she asked him why he had trouble with sleepovers.

Why do you have trouble with sleepovers?

He didn’t answer her question. He couldn’t because here was the real question: Why did she keep writing to him? He wasn’t sure what she was doing this summer, but he assumed she was taking some college-level summer classes. He heard a rumor once that Amy took courses through UCLA Extension every summer, and had enough credits to start college a year from now as a second-semester sophomore. It probably wasn’t true, but that’s what he’d heard. There were a few stories like that about her.

After a week, he felt guilty for not responding and wrote this:

Sorry I couldn’t write back for a while. I got really busy. Can you believe school is about to start? I’m looking forward to the training sessions for this job. That should be interesting. Do you attend, too? Your mother didn’t say in her letter.

He sounded like a dork. Oh well. At least he’d written her back.

No, I won’t go to the training sessions. Why do sleepovers make you nervous?

How did it go? My mother said you were there but you were pretty quiet the whole time and then you left early, which makes me nervous that maybe you’ve changed your mind. Please don’t change your mind, Matthew.

Matthew? Are you there? Please write back. My mom said you came to the training session today but she can’t tell whether you’re really interested in this job. She has her doubts. I told her to give you a chance. Everyone else is doing this to round out their college application. With you, it’s different, I think. Maybe I’m wrong about that. But please don’t quit.

She was right about this much: he wanted to quit. One “training session” with Nicole, Amy’s mother, talking about choking hazards and seizure risks was enough to make him feel like there was no way he could do this.

Seizure risk?

Just hearing that phrase made him start to sweat and wonder if he was having one.

At the end of the session Nicole made it clear: “We’re replacing adult aides with peers because this is Amy’s last year of high school and she wants to learn about making friends before she goes off to college. This is her number one goal for the year and we’re hoping you all can help her achieve it.”

Your mom has pretty high goals for your peer helpers. I’m not sure I’m cut out for this.

What goals?

She wants each of us to introduce you to five new people a week. Does that seem like a high number? It does to me, but then, as you know, I don’t have a ton of friends, so I’m not sure.

PLEASE don’t worry about it.

He

was

worried about it. Very worried. Now that he’d told his mom about the job, though, he wasn’t sure if she’d let him back out.

“Wait a minute,” his mom said, after he told her he might be working as Amy’s aide one day a week. “Do I remember this girl? From sixth-grade chorus? Did she sit in a chair up front and sing louder than everyone else?”

“Yes,” he said, embarrassed by the memory.

“And she waved her hands the whole time, like she was conducting the audience?”

“Yes,” he said. This conversation made him think of a line Amy had written in one of her first emails to him.

I want you to tell me when I’m doing stuff wrong.

That request alone was enough to worry him: Where would he begin?

His mother clapped her hands and threw her head back, laughing like she hardly ever did anymore. “I

loved

that girl. I always wondered what ever happened to her.”

Okay. See you at school. I’m not scheduled to work until Friday, which pretty much confirms that your mom thinks of me as the least promising of your peer helpers. I’m fairly sure she isn’t saving the best for last. I think she’s hoping someone else will show up between now and then. If that doesn’t happen, I’ll see you on Friday, I guess. . . .

Sorry to harp on this but why don’t you like sleepovers?

T

HE NIGHT BEFORE SCHOOL

started, Matthew lay awake in bed and tried to picture himself doing this job—walking beside Amy between classes, carrying her books as he’d only seen adults do in the past. Maybe it would work out okay, but it didn’t seem likely. Because of her walker, Amy couldn’t really walk and talk at the same time. There would be silences that could be excruciating. Until this summer when she emailed him, he’d never known she was funny and easy to talk to. But what good would that do if they couldn’t talk? Not much.

Then there was Amy’s mother who had high expectations and obvious doubts about him. All through the training sessions Nicole kept saying, “If you don’t feel comfortable with any aspect of this job, please let me know,” looking straight at him as if she could tell he felt uncomfortable with pretty much all of it.

He’d only applied because Amy wrote him in July and asked him to. And that was such a surprise he couldn’t think of any reason to say no, though he probably should have.

They didn’t know each other, really. They’d only had that one conversation that he still thought of as horrible and awkward, though apparently Amy didn’t.

Maybe it wasn’t right to say he didn’t know her at all. He still remembered the first time he saw her in second grade, and the speech the teacher made before she arrived, about how Amy might “look different on the outside but inside she’s exactly like everyone else.” Because the teacher didn’t explain what she meant by “look different,” Matthew imagined a girl covered in fur, or wrinkly skin with bug eyes like Yoda. That year, Matthew had discovered the Human Freak section in the

Guinness Book of World Records

, and used to stare at pictures of the men covered in warts and the women with heavy beards. When Amy appeared just before lunch, inching into the classroom with her wheeled walker in front of her and an adult on either side, he was disappointed.

Mostly she

did

look like other girls. She had curly blond hair that hung down her back and she wore a flowered pink dress. Sure, she couldn’t walk without her contraption, but beyond that she had no particularly freakish qualities. Yes, her mouth hung open. Yes, she drooled enough to wear a bib most days—which was embarrassing, maybe—but she wasn’t a

true freak

like he’d hoped. She was most interesting when she tried to talk at morning meeting, where everyone else sat on a carpet square—except Amy, who sat in a low, blue plastic rocking chair she sometimes fell out of. She never raised her hand to speak. Instead she rocked in her chair and squawked like something was caught in her throat.

“Oh my goodness,” the teacher said the first time Amy did this. She looked at Amy’s aide. “Is she

all right

?”

“She has something she wants to say,” the aide said.

They all waited while Amy’s mouth opened and closed. No sound came out. A minute ticked by and finally the teacher couldn’t wait anymore. “We’ll let Amy gather her thoughts and come back.”

The next year they moved up to third grade, where the teacher, Mrs. Dunphy, talked about Amy when she was out of the room. “The doctors predicted that Amy would be a vegetable for the rest of her life, and look how far she’s come! The most important thing for you all to know is that she’s extremely bright with a very high IQ.”

This was news to Matthew, who was in the highest reading and math group. For the rest of third grade, Matthew waited for Amy to do or say something extremely smart. Maybe she did. Mrs. Dunphy called on her regularly but the problem was no one—including Mrs. Dunphy—understood anything Amy said.

She spoke in a language that used no consonants, only a long string of vowels. Matthew tried to imitate it once, and sounded like he did when a doctor asked him questions with a tongue depressor in his mouth. Amy’s aide understood a few words:

Bathroom. I need a break.

Some girls

pretended

to understand secrets Amy whispered in their ear at recess. They went up one by one, held their ear to Amy’s mouth, and ran off to giggle on the bench. The joke was ended by a recess monitor who wasn’t sure, but thought the game might be hurting Amy’s feelings. Matthew overheard the conversation between two teachers. “I thought Amy liked it,” one of them said. “It’s better than sitting by herself the whole recess, isn’t it?”

“No,” the other woman said. “They’re making fun of her and she knows it.”

Matthew noticed that neither one of them

asked Amy

, which he supposed made sense. They all knew by then Amy wouldn’t have answered with a simple yes or no. She never did. She had long, complicated answers for every question she was asked, answers no one ever understood. Sometimes Matthew watched adults pretend to understand Amy—laugh at one of her “jokes” or nod at a comment—and he thought:

they look like the freak, not her.

In fourth grade Amy started using a talking computer, programmed with phrases that required pushing only a few buttons for Amy to “say” them. There was also a keyboard with a word-prediction program. At recess, all the kids gathered around and tried to get Amy’s new computer to swear. Which made Amy laugh for ten minutes, then start to cry. “PLEASE STOP,” she typed. “NO. NO. NO.”

The talking computer changed how everyone saw Amy. She still drooled and was messy when she ate. Sometimes she got too excited in class and choked on her own spit. But now she sat with other kids in reading and math groups. They figured out that Mrs. Dunphy was right the year before—Amy could read and spell, better than most of them. She wasn’t the best math student in the class, but she was in the top three.

She had good control of the one hand she typed with, but the other went spastic at times and knocked over messy things like hot coffee and boxes of pencils. When she made messes, though, she wasn’t punished like other kids, because she wasn’t like other kids. Her clothes were different. So were the books she read and the shows she watched. So was the fact that she always had an adult beside her.

She’s not really a kid,

Matthew decided by sixth grade.

He watched her less by that point because he had his own problems by then. New ones that had cropped up out of nowhere and scared him a little. A voice in his head telling him to do things. Wash his hands twice before lunch, up to his elbows. Wash them again after lunch. His new fears were related—slightly—to his old fascination with bearded ladies and wart-covered men. Freakishness could happen to anyone at any time, he’d learned. Kenny Robinson lost half a finger in an accident with a boat-engine propeller. Now he pointed with his stump, which scared Matthew because lots of things scared him these days. A month before sixth grade started, his parents told him they were getting divorced but he shouldn’t worry because it was a friendly divorce and what everyone wanted.

It wasn’t what he wanted, but he felt too scared to point that out, afraid if he did, it wouldn’t matter anyway.

In seventh grade, he and Amy had English together and once she asked him to help her print an essay. Because he was curious, he sent two copies to the printer and secretly kept one. It was a personal essay in response to the question:

What worries you most about the future?

It was a terrible topic for someone like Matthew, who already worried too much. They’d spent the last two days in class reading one another’s essays and offering “feedback,” which meant everyone wrote, “Good job. I like your honesty,” on the bottom of everyone else’s essay. Reading other essays, Matthew had learned that some people were too honest: “What I worry most about in the future is getting fat.” Or else they tried too hard: “I’m most worried about air-and-water pollution.”

Matthew, whose parents had gotten divorced the year before, thought of saying he worried most about his mother, who didn’t do anything besides work, come home, and watch TV. He didn’t write about that because if he were honest and his mother read it, she might get even more depressed than she already was. In the end, he wrote the only thing he could think of: “I worry most about worrying too much.” After such an honest first sentence, he drifted into safe generalizations: “We have grades to maintain, along with family responsibilities. Someday we’ll have to worry about college applications and how we’ll pay for college, if we can get in. After that, I worry about jobs and what the cost of energy will be.”

It went on like that for a few more paragraphs. At the bottom, most people wrote: “Good job, but you might want to get more specific.” He wanted to see what Amy, who had more to worry about than the rest of them, wrote. Was it mean to think this? He wasn’t sure.

Then he read Amy’s essay:

I’m not sure I

do

worry about the future.

I don’t know what lies ahead but I know I’m not scared of it. I’m in no rush to be an adult, but I suspect when I get there, I’ll discover it’s easier than being a kid. There won’t be so many ups and downs. Or crises that get talked about as if they’re the end of the world. I think we’ll all come to understand that there isn’t any one big test or way to validate ourselves in the world. There’s just a long, quiet process of finding our place in it. Where we’re meant to be. Who we’re meant to be with. I picture it settling like snow when it happens. Soft and easy to fall in if you’re dressed right. I think the future will be like that.

Oh come on,

Matthew thought. Was she

serious

? Was this a joke? Or—he had to admit this felt like a possibility—was she

completely crazy

? She could barely walk, she couldn’t talk at all, and she wasn’t worried about the future? It made no

sense.

It made him

mad.

Amy, who couldn’t walk in snow, imagined a future that felt like falling into it?

Later, when the best essays got pinned to the board of the classroom, he read the comments she got: “Oh my God, this is so amazing!”

“You are an awesome writer!”

Matthew felt small and stupid.

And then last year, at the end of eleventh grade, the whole school got to read one of Amy’s essays when it was printed in

Kaleidoscope

, the school literary journal. Hers was the piece everyone talked about:

Lucky

By Amy Van Dorn, grade 11

When people first see me, they may not believe this, but most days I don’t feel particularly disabled. In the ways that matter most, I believe I am more blessed by good luck than I am saddled by misfortune. My eyes are good, as are my ears. I’ve been raised by parents who love me as I am, which means that even though I can’t walk or talk well, I’m reasonably well adjusted.

I know that for a teenage girl in America, this is saying a lot. I don’t want to be thinner than I am, or taller. I don’t look at my body parts and wish they were bigger or smaller. In fact—and this will surprise many people—I don’t wish I was fine. I don’t pine for working legs or a cooperative tongue. It would be nice not to drool and warp the best pages of my favorite books, but I’m old enough to know a little drool isn’t going to ruin anyone’s life. I don’t know what it would feel like to be beautiful, but I can guess that it makes demands on your time. I watch pretty girls my age and I see how hard they work at it. I imagine it introduces fears I will never experience: What if I lose this? Why am I not happier when I have this?

Instead of beauty, I have a face no one envies and a body no one would choose to live in. These two factors alone have freed up my days to pursue what other girls my age might also do if their strong legs weren’t carrying them to dances and parties and places that feed a lot of insecurities. Living in a body that limits my choices means I am not a victim of fashion or cultural pressures, because there is no place for me in the culture I see. In having fewer options, I am freer than any other teenager I know. I have more time, more choices, more ways I can be. I feel blessed and yes—I feel lucky.

Reading it the first time, Matthew felt angry all over again. Surely she didn’t

really

feel this way. He thought about her seventh-grade essay where she said she wasn’t worried about the future. Here she was again—the unluckiest person he could imagine—saying she felt

lucky

? It had to be an act.

But he wanted to know: Why did she work so hard at it?

In English, Ms. Fiorina, famous for wasting class time discussing issues that were never on any test, asked what people thought of Amy’s essay. Because Amy wasn’t in their class, they were honest. One girl raised her hand. “It made me want to cry. If I had her problems I’d probably kill myself.”

“Maybe that’s a little extreme, Paula, but that’s her point, right? When you’re a teenager being different—if it’s not by choice—seems like the worst thing imaginable. But is it really?”

“But she’s not just different. She can’t

talk

.”

“I saw her choke once,” Ben Robedeaux said without raising his hand. “It was really weird. She fell out of her chair and had like this seizure.”

Matthew was surprised. He’d never heard that story.

A few minutes later Matthew raised his hand. Usually he didn’t participate in these discussions, but this time he had something he wanted to say. “I’ve known her a long time and I don’t think she really feels this way. She wants everyone to have this image of her as happy and well adjusted. I just don’t think it’s true.”

“Interesting,”

Ms. Fiorina said, looking up like what he’d said really

was

interesting. “But is that a bad thing? She’s a person with a disability conveying the message,

Hey, my life isn’t all tragedy.

Do we hear that message enough?”

“But it

is

a tragedy,” a girl in the back row said. “I mean, I’m sorry, but it

is

.”

“Explain what you mean, Stacey

.

”

“She can’t

talk

.”

“But she communicates, right? She writes beautifully and some of you have had classes with her, right? You know her pretty well. Matthew says he doesn’t think she’s telling the truth. Maybe he knows something the rest of us don’t.”