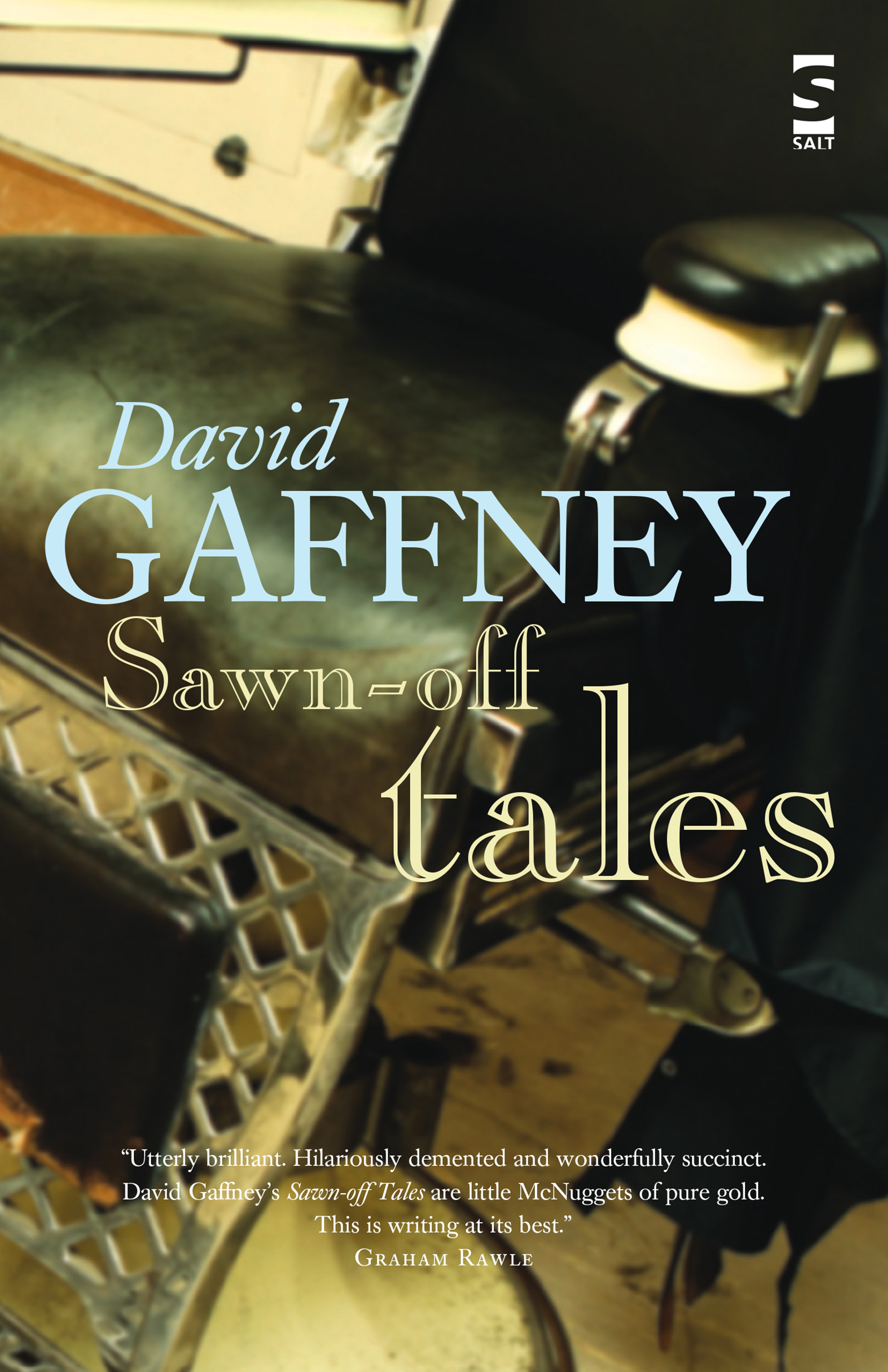

Sawn-Off Tales

Authors: David Gaffney

Sawn-off Tales

David Gaffney is from Manchester. He is the author of

Sawn-off Tales

(2006),

Aromabingo

(2007),

Never Never

(2008),

Buildings Crying Out, a story using lost cat posters

(Lancaster litfest 2009),

23 Stops To Hull

short stories about every junction on the M62 (Humber Mouth festival 2009)

Destroy PowerPoint

, stories in PowerPoint format for Edinburgh festival in August 2009,

The Poole Confessions

stories told in a mobile confessional box (Poole Literature Festival 2010) and has written articles for

The Guardian

,

The Sunday Times

,

The Financial Times

and

Prospect

magazine.

Sawn-off Tales

David Gaffney

London

Published by Salt Publishing

Dutch House, 307â308 High Holborn, London WC1V 7LL United Kingdom

Â

All rights reserved

Â

© David Gaffney,

2006, 2010

Â

The right of David Gaffney to be identiï¬ed as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section

77

of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act

1988

.

Â

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Â

Salt Publishing

2010

Â

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

Â

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,

or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Â

ISBNÂ 978 1 84471 838 2

electronic

Your Name in Weetos

I

WAS A

stacker, working nights. I had been incubating a desire for Mildred for a long time and that night she was nearby, on chillers, wearing plastic gloves and a paper hat. I was on cereals, yard after yard of gaudy motifs repeating like a nagging one-note riff. I shuffled the boxes around and called her over.

She laughed. âMy name in Weetos. Thanks, mate.' Then she went to the deli and daubed

William

onto the sneeze shield with squeezy-cheese. I was going to say something else when the shift super arrived and broke us up. We never spoke again. At the end of the summer she went to university and I stayed on stacking. Stacking suited me. You filled the shelves, the stuff got sold, you filled them up again. There were other female stackers, but I wasn't interested. To my mind, a moment can be worth a whole relationship.

Â

Â

The Lost Language of Hairgrips

T

HE TINY THINGS

she had. The tweezers, the eyelash curlers, the cuticle pushers, all of them so small, so brittle. That's what I miss most about Joanna. The little things. Not the little things she did, or the little things she said; the actual little physical things she owned.

Without Joanna's little things littering the place, everything looked giant. Overstuffed chairs, hulking shampoo bottles, breeze block soap. I possessed nothing small enough to be mislaid and this thought disturbed me, made me feel feline and uneasy.

One night I was rubbing one of Joanna's hairgrips against the cheese grater, sending orange plastic slivers spinning into my soup, when I realised this obsession was completely wrong. What I needed were some little things of my own.

I discovered the answer in the aisles of the DIY store. Here were a billion little things for men to own and cherish; curious devices like the discarded tools of a lost civilisation. I filled my trolley and wheeled it to the checkout, but before I'd even paid I met Pat. Pat had just one item in her trolley â a giant architectural plant â and, following my eyes, she told me that there was nothing she hated more than little things. When her last fellah brought home a pathetic little plastic man to wave at his toy locomotives, it was the final straw.

âThere's something sinister,' Pat explained to me in the car, âabout little things. I worry that they will divide and multiply in the night, creep inside me, and possess me. You know where you are with a big thing. A big thing would never do that.'

I fell in love with Pat. Everything about her was big. Her house had huge bay windows like a comforting bosom into which I sank each night. I forgot completely about the little things. Think big, Pat said, and I did.

Â

Â

Last to Know

H

E SHOWED ME

the back of my head in a mirror and I nodded. â£6.50 then,' he said, and pressed the foot pedal. The hydraulics sighed as I sank to the ï¬oor.

âI normally pay five.'

He indicated the price list. âIt's been £6.50 for a while.'

âYes, but . . .'

What had happened? I was regular. Only new customers paid full. It was never spoken of, but that was the system. The barber could tell that someone else had cut it; the blending between the longer and shorter sections was poorly executed.

âLook me in the eye,' he said, âand tell me you haven't been to anyone else.'

âI haven't been to another barbers in years.'

The barber sucked in his lower lip. âSo we're talking home clippers.'

âYes,' I said, and felt my cheeks redden in shame.

âOK. Call it £5.50. I know you won't do it again.'

Â

Â

Flying Lessons with Gary Numan

H

IS FACE WAS

scratched, his clothes dishevelled, but he looked alright, not like he would lunge at you with a sharpened toothbrush or anything. He was going to watch Man City training â it was free and it passed a morning â and all he needed was the bus fare, so I gave him £1.40. He told me about his son, well his stepson really, who had got pally with Gary Numan, the singer. But Mr Numan didn't sing anymore, he ï¬ew planes.

This relationship infuriated my new friend â did I know what music was all about? The Moody Blues were what music was all about. But the year before, when the hostel got him a free ticket to see his heroes at the Apollo, he leapt onto his seat, shouted, âJustin, Justin', and a huge fuck-off bouncer chucked him out. âIt's all,' he spat onto the road, âsynthesisers now.'

Â

Â

Intimate Zone

I

COULDN'T BELIEVE

it. He pushed through the door and squeezed himself onto the same seat. Right next to me, you know, touching. I told him I wouldn't be long but he starts right in with this stuff about different cultures. âWe English,' he says, âwe worry too much about personal space. I've just landed back from Spain and they have a completely different attitude. You are sitting on a deserted beach and another group of Spaniards appear? They set up right next to you. On an underground train alone? The next Spaniard will plonk down on the same seat. It's a liberating attitude. We English are too distrustful.'

There was nothing I could do to get rid of him. So I climbed off, yanked up my jeans and ï¬ushed. The cold water splashed up onto his bare skin and he just sat there looking up at me.

Â

Â